Cherry is an embarrassing bid for prestige from Marvel’s biggest hitmakers

Note: The writer of this review watched Cherry on a digital screener from home. Before making the decision to see it—or any other film—in a movie theater, please consider the health risks involved. Here’s an interview on the matter with scientific experts.

Cherry is a bombastic epic of suffering: the empty, super-sized IMAX version of an “important” drama. At 140 minutes, it’s about as long as an Avengers movie, and as subtle, too. That’s no random comparison or coincidence. Its directors, Joe and Anthony Russo, are hot off of Endgame. How do you follow the biggest movie of all time? If you’re these two, you make like Tom Jane and pivot to a gritty addiction drama to prove you’re serious artists. Yes, Cherry is the duo’s Junk—a fake movie that might leap to mind even if the filmmakers hadn’t cut their teeth directing episodes of Arrested Development, including one featuring a callback to that very joke. Chronicling two decades of anguish and misfortune in the life of a tortured young man, the film is as thirsty for prestige as its characters are for something they can pop, shoot, or snort. Yet it’s been made with all the restraint and nuance you’d expect from—in the immortally narrated words of Ron Howard—a rigidly formulaic popcorn movie.

On blockbuster duty, the Russos are no slouches. Their superhero spectacles have a slick snappiness, honed over years spent punching up the visual comedy of network sitcoms. But their approach is an egregious mismatch to Cherry’s grim source material. The film’s based on the semi-autobiographical novel by Nico Walker, an Army veteran who turned to drugs to cope with his trauma and bank robbing to pay for the drugs. (He wrote the book behind bars.) The Russos mainly treat his lightly fictionalized narrative like an opportunity to flex some unused stylistic muscles—to try out all the tricks they couldn’t while adhering to the Marvel template: dolly shots, jump cuts, extreme angles, desaturated drug-trip sequences, and exaggerated changes in aspect ratio. At one point, they shoot a rectal exam from the rectum’s perspective. It may be the defining image of a film so far up its own ass.

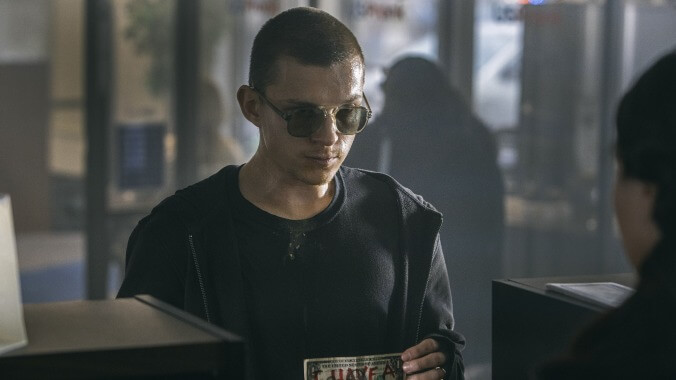

For a while, the two seem content doing subpar Scorsese. (That filming began in October of 2019, right around the time Marty made his controversial remarks about Marvel movies, almost leads one to wonder if the studio’s most reliable hitmakers didn’t set out to prove they could do what he does, easy.) Cherry begins with one of those “How did I get here” moments, as an outlaw (Tom Holland, also on leave from Disney) turns to address the audience during a bank robbery. These breaks of the fourth wall will trade off with a running voice-over commentary as the film rewinds several years to its unnamed protagonist’s salad days as an Ohio college kid, whispering sweet nothings to campus girlfriend Emily (Ciara Bravo), the ill-defined romantic center of his world. Those wondering how Goodfellas might play if it were narrated by the bag-obsessed teen from American Beauty now have their answer.

Cherry has the “and then this happened” dramatic shapelessness that often characterizes memoir, but with none of the tradeoff specificity. Its script, by Jessica Goldberg and the directors’ sister, Angela Russo-Otstot, preserves a novelistic scope, unfolding across six chapters, plus a prologue and an epilogue. But it plays more like an adaptation of a Wikipedia summary, skimming whole paragraphs of incident in the style of dorm-room staples. Once Holland’s vacuous lover boy combats his breakup blues by enlisting, the film segues into a streamlined music-video Full Metal Jacket, allowing the Russos to montage through basic training en route to their own addition to the canon of long-take, entrails-out battle sequences. (Is the faint military critique atonement for their time in the trenches of a franchise with ties to recruitment efforts?) Once back in Ohio, Walker’s onscreen surrogate plummets into a wannabe Trainspotting, regaling us on the highs and lows of “dope life,” with Jack Reynor as an obnoxious dealer referred to, simply, as Pills & Coke.

For Holland, the MCU’s youngest star, this is a blow to typecasting. Sliding off both the spandex and gee-whiz innocence of Peter Parker, he gets to sweat and curse and jerk off and fire a gun and slide a needle into his arm. Cherry’s nearly as bleak, and unheroic, as last year’s change of pace for the actor, Southern Gothic misery ensemble The Devil All The Time. But he’s got no actual character to play here—the lack of a name is apropos for such a thinly sketched cipher, a guy who seems half-there even before heroin bottoms him out. (He’s a zombie on and off the wagon.) Bravo fares worse in a role that becomes a different kind of thankless every chapter, as Emily glides from idealized dream girl to ceaselessly loyal military wife to zoned-out fiend screeching about when they’re going to score next. Pulled from Walker’s pages or not, the dialogue does no one any favors. “Basically, I was being a sad, crazy fuck about the horrors I had seen,” Holland bluntly self-diagnoses. Reynor’s dirtbag puts it even less eloquently: “You’re a junkie motherfucker with PTSD!”

This is a film with nothing new to say about love, war, trauma, addiction, crime, or America. It blows through these topics on a bender of hyper-stylization, indifferently twisting its true story into the shape of other, better movies. By its final stretch, the delusions of grandeur have caught up with the showboating, especially during a laughably protracted slow-motion climax and a denouement that just had to have been temp-tracked to “On The Nature Of Daylight.” It leaves you wondering if working with a $300 million budget rots your brain or at least kills your capacity to make anything small or remotely real ever again. Either way, you’d think a tenure on some of TV’s most post-modern comedies would, at the very least, give the Russo brothers a more pronounced self-awareness about the line separating seriousness from mere pretensions to it. Community couldn’t parody this movie better than it parodies itself.