Children Of Blood And Bone is less a novel than a YA movie franchise in waiting

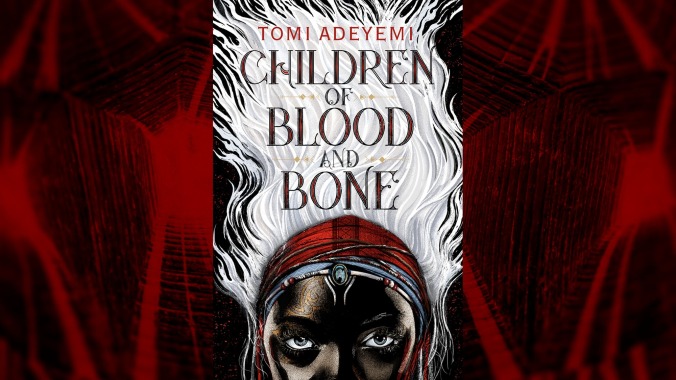

Children Of Blood And Bone made headlines before the book was even published, thanks to a pair of flashy deals betting on Tomi Adeyemi’s planned Legacy Of Orisha trilogy to be the next YA sensation. Macmillan paid a reported seven figures for Adeyemi’s trilogy, while Fox is already adapting Children Of Blood And Bone into a film. The deal, one of the highest payments for a debut YA novel ever, is all the more remarkable for Adeyemi’s age: She’s just 23, recently graduated from Harvard. Does the book live up to its hype?

Not really. Adeyemi cites Avatar: The Last Airbender as one her primary inspirations for Children Of Blood And Bone, and that influence isn’t especially subtle. Adeyemi’s story follows Zelie, who lost her mother as a girl during a purge of magic users ordered by Orisha’s evil king, Saran. A chance encounter with someone who might be able to restore her world to the way it once was leads Zelie to set out with her loyal bull-horned giant lion and nonmagical older brother on a quest to master her powers and defeat Saran. They have a deadline set by a celestial event and are also pursued by Prince Inan, who’s torn between doing the right thing and fulfilling his duty to nation and family. Add in the narrative structure and cross-cultural love story borrowed from Sabaa Tahir’s An Ember In The Ashes, which Adeyemi also cites as a major influence, and precious little about Children Of Blood And Bone feels original.

Adeyemi does have some promising ideas of her own. A fantasy version of Nigeria, Orisha was once home to 12 Maji clans, each with a patron god or goddess and a signature magical ability that manifests in some members at age 13. Saran cut off access to magic and purged all of the adult Maji, leaving their children disempowered in every sense of the word. Their language and rituals are outlawed and those who have the potential to manifest magic—marked by their white hair—are abused or enslaved. Zelie sets out to restore magic, Inan to crush it, but their views on vengeance, oppression, and the uneven distribution of power shift as they interact. Children Of Blood And Bone isn’t nearly as good as Black Panther, but it is worthwhile complementary reading.

Adeyemi’s magic system also fails to live up to its potential. Zelie is a Reaper with power to command the spirits of the dead, but what that means is poorly defined. In one scene Zelie is able to animate water in an arena by calling on the vengeful ghosts of those who died there to fight for her to earn peace. In another scene she repeatedly creates animations for practice with no reference to the spirits at all. Her mother also apparently used necromantic energy to hold Zelie in place so she could comb her hair, which seems like child or spirit abuse. Inan’s ability to read and control minds is more defined, and the descriptions of how it manifests are beautiful. It’s a fascinating power for an antagonist, forcing empathy on him as he experiences the pain and fear of others. It’s a shame that Adeyemi doesn’t cause more conflict by having Inan use his power on Saran to show why the king thinks his actions are righteous. Better knowing his father could test Inan’s loyalties even further. Instead, Saran is presented only as a cruel abuser, making him just as two-dimensional a villain as Avatar: The Last Airbender’s Fire Lord Ozai.

The novel is also overly long and repetitive, with too much time spent on the three narrating characters restating their motivations and rehashing events that happened just pages before. This problem is especially egregious with the character of Amari, Inan’s sister, who decides to rebel against her father after he kills her beloved handmaiden. A multiple narrators technique works well when they’re in different places or doing very different things, but Amari spends the vast majority of the book accompanying Zelie. It feels like she’s getting time here just because she’ll be more important in the sequel. The pressure to set up the rest of the series is palpable in the conflicts Adeyemi introduces and the answers she holds back. Amari’s first chapter sees the princess embroiled in courtly intrigue and pushed to try beauty routines to lighten her skin. That world immediately fades into the background, but it hints at the possibility of a very different book to come.

Children Of Blood And Bone will likely make a better movie than a book, since the screenplay will strip away the prattling internal monologue and take advantage of the story’s cinematic bent. The novel feels written for the screen, complete with cross cuts, chase scenes, and explosive fights. Considering how terrible M. Night Shyamalan’s The Last Airbender was, this may be the closest fans of the TV show will get to seeing that story brought to life on film. Hopefully Adeyemi’s writing becomes less beholden to the rigors of a YA film trilogy over the course of her books.