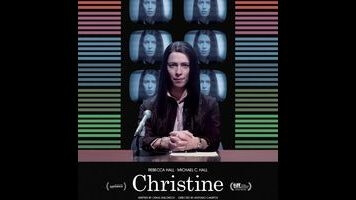

In what is apparently one of the most remarkable cinema-related coincidences of all time, Sundance 2016 premiered a pair of films, made independently by completely different people, that more or less negate each other’s very existence, like matter and antimatter. The first of the two to be theatrically released, back in August, was Robert Greene’s quasi-documentary Kate Plays Christine, which observes actor Kate Lyn Sheil as she prepares to take on the role of Christine Chubbuck, a TV journalist who committed live, on-camera suicide in 1974. The biopic that Sheil was allegedly preparing for didn’t actually exist (more accurately, it existed only as part of Kate Plays Christine itself), and Greene’s movie ultimately makes a very persuasive argument that no such biopic should exist—that any conventional dramatic treatment of Chubbuck’s sad story would inevitably land in the ugly swamp of voyeuristic exploitation. But now along comes Christine, a fairly standard biopic directed by Antonio Campos (Afterschool, Simon Killer) and starring Rebecca Hall as Chubbuck, and it’s incisive and empathetic enough to serve as a refutation of its own.

Much of the credit for that goes to Hall, who makes Chubbuck a discomfitingly awkward presence (in a way that seems fairly accurate, based on what little real-life footage still exists), but not a figure of ridicule. First seen conducting an imaginary interview with President Nixon, the 29-year-old reporter is at once enormously ambitious and paralyzingly insecure, a combination that manifests itself as what can only be called neurotic arrogance. She consistently butts heads with the station manager (Tracy Letts) of the tiny local affiliate for which she works in Sarasota, Florida—in particular, she’s disgusted by his predilection for tawdry stories involving sex and violence, as opposed to sober, hard-hitting investigation. The station’s news anchor, George Ryan (Michael C. Hall), does his best to encourage Christine and lend a sympathetic ear, but their friendship is complicated by her massive crush on him, which at first seems unrequited and then, when he starts flirting with her a little, inspires her to retreat even further into a protective shell.

As Kate Plays Christine noted/warned, there’s a high degree of difficulty here. Tackling this life with honesty and respect demands a tricky balancing act between context and character, which first-time screenwriter Craig Shilowich performs remarkably well. Christine explores the numerous ways that the era’s open sexism contributes to Chubbuck’s professional frustration, and does so without pretending that her own eccentricities weren’t also a factor. Likewise, the film deals head-on with Chubbuck’s well-documented despair about still being a virgin at 29, but avoids creating the impression of a woman who offed herself simply because she couldn’t get laid. Campos wisely tones down the extreme formal aggression that distinguished his first two features, trapping Rebecca Hall’s abrasive, live-wire performance within sterile flatness. The movie contains too many internal contradictions for any facile armchair diagnoses. Rather than make a futile attempt to explain why Chubbuck did what she did, Christine embraces the irresolvable.

What of the ghoulishness, though? Kate Plays Christine ends with Sheil struggling to perform Chubbuck’s on-air suicide, and the doc concludes that our desire to see it (people have spent decades trying to determine where a recording of the actual broadcast may have wound up) is fundamentally unhealthy. That may be so, but since Christine succeeds in imagining Chubbuck’s life to be as arresting as her death, watching it isn’t exclusively a tense countdown toward a horrific money shot (so to speak). And while the film does depict the suicide, that moment isn’t nearly as memorable as a pitch-perfect coda involving a fairly minor character, which combines generosity, poignance, and rueful irony in unnerving proportions. This magnificent ending reverberates backward, imbuing everything that precedes it with a clearer sense of purpose. It’s also as serendipitous a “fuck you” toward Kate Plays Christine as the ending of Kate Plays Christine is a “fuck you” toward Christine. Indeed, seeing both movies is a richer experience than seeing either one alone. One says nobody should make a Christine Chubbuck movie. The other defiantly says, “We’re gonna make it after all.”