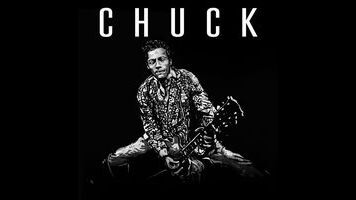

Chuck Berry’s final album makes a casually profound closing statement

Barring any additional posthumous releases, the last song on the last album that Chuck Berry ever recorded will be “Eyes Of Man,” a midtempo blues number with a vocal performance more spoken than sung. It clocks in at just a little over two minutes—at the end of a 10-track LP that doesn’t quite reach a total running time of 35 minutes—and it offers up a bit of homespun wisdom from a man as he was approaching 90. Berry talks about the male hubris in building “temples” to themselves, and how the women in these guys’ lives are responsible for making sure their structures endure. In his refrain, the Rock And Roll Hall Of Famer advises younger listeners on how to deal with “those who do not know and do not know that they do not know,” as well as “those who know that they do not know” and “those who do not know that they know.” These words are initially confounding, but soon begin to make a kind of deeper sense. Then, just as it feels like “Eyes Of Man” is about to say something profound, it ends. And nothing comes after.

Chuck Berry is one of our culture’s more complicated figures. His life story represents the best of American opportunity, and the worst of fame and privilege. He had more than 60 years in the music business, a span during which he wrote and recorded dozens of songs that have become rock ’n’ roll standards; yet because his heyday was in an era that prized singles over full-lengths, he didn’t leave behind any one definitive album. When Berry died in March, luminaries like Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards rushed to proclaim his singular genius and influence, while also admitting that as a person, he could be difficult. (In Mikal Gilmore’s in-depth obituary in Rolling Stone magazine, Richards is quoted as saying, “I couldn’t warm to him even if I was cremated next to him.”)

It would’ve been hard for Berry to defend his life and summarize his art on Chuck, which was both his final album and his first new collection of recordings since the 1979 record Rock It. So he didn’t really try. Recorded off and on over the course of several years (mostly in Berry’s hometown of St. Louis), Chuck is the kind of record a veteran working musician makes, and not what anyone would consider a “comeback” or self-epitaph. It doesn’t really compare, say, to Warren Zevon’s elegiac, self-aware last album, The Wind, or June Carter Cash’s feisty, heartwarming goodbye, Wildwood Flower. Aside from “Eyes Of Man,” Chuck is low on “there’s something important I need to tell you” songs.

That’s not to say that the new album is completely unaware of its context. Two songs on the record overtly nod to Berry’s back catalog. “Jamaica Moon” is a rewrite of “Havana Moon,” a lilting tropical exercise that failed to become a hit back in the ’50s—something Berry attributed to Castro’s revolution in Cuba. And “Lady B. Goode” is a sequel of sorts to “Johnny B. Goode,” concerning a woman who supported a fledgling rock star.

There are a lot of songs on Chuck that salute women. In addition to “Eyes Of Man” and “Lady B. Goode,” the album opens with the rollicking love song “Wonderful Woman,” and includes the country-inflected barrelhouse ballads “You Go To My Head” and “She Still Loves You.” Both “Darlin’” and “Dutchman” were written from the perspective of a grizzled oldster, reflecting on mistakes made and the woman he should’ve cherished more. And the whole record is dedicated to Berry’s wife of 68 years, Themetta.

For those who’ve read about Berry’s history as a womanizer and scoundrel—which landed him in court or in jail multiple times throughout his life—it’s hard not to hear much of Chuck as an apology, aimed at the person who stuck with him through the kind of scandals that would’ve ended nearly any other marriage. From 1979 through the end of the 20th century, Berry would occasionally tell people that he didn’t have much interest in writing or recording anything new because he did just fine touring around the world, playing the old hits. But then suddenly, at the end of his life, he picked up a pen again and headed back into the studio—almost like he was anxious to settle unfinished business.

But this is only speculation—and it’s important to note that it’s not necessary to even be aware of Chuck Berry to enjoy Chuck. The songs here don’t really rise up to the level of a “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” or “No Particular Place To Go,” but the album as a whole has a very loose, appealing sound. Despite guest appearances by Gary Clark Jr., Tom Morello, and Nathaniel Rateliff, nothing about Chuck comes off as grandiose or fussily reverent. The sessions prominently feature Berry’s children on guitar and background vocals, which better describes the vibe of this record: It’s like a family project, hammered together in the backyard on weekends.

Casual rock fans who only know the basics of the Berry discography—the “Roll Over Beethoven”s and “Maybellene”s—may be surprised by how eclectic Chuck is. But those who are aware of how the guitarist started a musical revolution by bringing hillbilly standards to black R&B clubs should appreciate the album’s range, which properly reflects Berry’s history. Songs here vary from the scorching throwback “Big Boys” to a joyously woozy live cover of Tony Joe White’s Tex-Mex novelty number “3/4 Time (Enchiladas).” Taken altogether, this is back-to-basics rock ’n’ roll, where the strands of country and western, roadhouse blues, and Broadway bravado that bound together the original rockers are all right there on the surface.

But because of who made this album and when it was released, it’s also tempting to listen between the lines. That, after all, is what being invested in pop is all about. If some 22-year-old nobody wrote and recorded the songs on Chuck, the album would still be pretty terrific, but it would take on a different meaning. Coming from the oft-inscrutable 90-year-old father of rock, the record carries with it all his baggage. And the questions it raises lend an animating tension to even the simplest songs.

Chuck’s a wonderful piece of American music, and ultimately as enigmatic and elusive as the man who filed it on his way out the door. Here’s its biggest mystery: Before he left us forever, did Berry consider himself one of “those who know” or “those who do not know”? And was he right or wrong?

Purchase Chuck here, which helps support The A.V. Club.