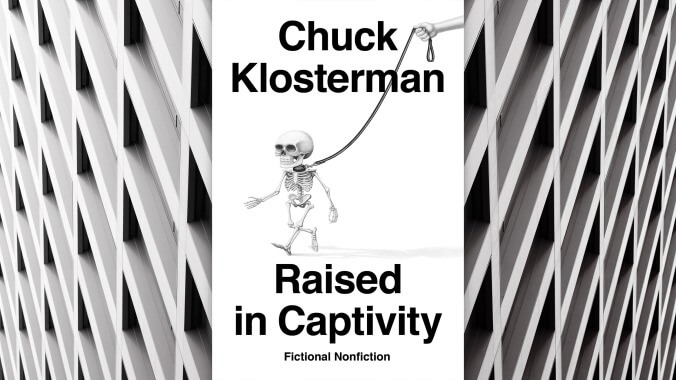

Chuck Klosterman’s Raised In Captivity is a bunch of empty premises

Billed as “microdoses of the straight dope” and somewhat charmingly subtitled Fictional Nonfiction, Chuck Klosterman’s Raised In Captivity is of a piece with his prolific cultural criticism. Best known for his music writing and the 2003 essay collection Sex, Drugs, And Cocoa Puffs, Klosterman comes across as familiarly irreverent in his first book of flash fiction. But while its tone may be alluring to fans, the collection is less clever, incisive short stories than it is akin to a series of premises pitched in a precocious TV writers’ room. Pilot season might do well to have Klosterman relate such jumping-off points, which is to say that the book sounds fun, but as a collection, it’s undercooked.

In one story, a middle-aged man pontificates about a job offer and then watches a humpbacked whale get struck by lightning, which suddenly changes everything he has ever thought about his life. In a story called “Cat Person” (yes, really), a police officer tells a reporter about a spate of attacks by a man who rubs an orange cat on strangers’ skin, causing them to exhibit self-destructive tendencies and “dark fantasies,” and attempt suicide.

Most often, Klosterman’s stories end abruptly (“Cat Person” with the revelation, if it can be called that, that the reporter—a woman—has six cats, to which a reader may be inclined to respond, “Okay, sure.”) Sometimes they end with a punchline. In one of the better stories, an obscure band, minus its bass player, finds out that one of its songs has become an anthem for white supremacists. They all express profound surprise. The story ends with the drummer mentioning that the bass player is working on a new song: “‘He told me the working title is “Bomb Israel.” But maybe we’ll want to retool that.’” It’s chuckle-worthy, but only for a moment.

Klosterman once helmed The New York Times’ Ethicist column, for a few years starting in 2012, and so it makes some sense that many of his stories deal directly with morality, albeit one that could be pitched in the Black Mirror writers’ room. Klosterman even winkingly refers to the show in one story; in it, doctors have figured out how to transfer the pain of childbirth from the patient to a “recipient.” A man considering the option with his wife says, “‘You know, I saw this British TV show on Netflix,’” but the doctor cuts him off: “‘I know what you’re going to ask, and it’s not like that at all.’” The man goes off on a tangent about the implications of “transferring” pain, but as with many stories here, as soon as things start to get interesting, Klosterman shuts it all down. “The papers were signed. The baby was perfect,” he writes, and that’s that. In another story, one gets almost too perfect a thesis statement for Raised In Captivity as a whole. A man named Trevor goes for a run and meets a man who knows everything about him—things no one else in the world could possibly know. “‘I get it,’ said Trevor, stopping the man as he described the Pink Floyd poster a fake girlfriend had once given him on Good Friday. ‘I get it. I mean, obviously I don’t get it get it, because what you’re doing is impossible. But I get that something impossible is happening… Let’s get this over with.’”

Klosterman’s best stories are those that deal with the ethics of his premise in a more meaningful way. In “Trial And Error,” a woman debates whether she should kill a wolf, in a world where it is widely thought that killing a wolf solves all of a person’s problems. The premise is almost groan-worthy, but what follows is a relatively comprehensive evaluation of the implications of such a world: “There were no analytical conversations or tiers of self-reflection that would resolve her dilemmas. It was time to try something radical. It was time to kill the wolf,” Klosterman writes early on, before launching into the nature of certitude. The ending is extremely clever, sneakily so.

The only problem is that for every good story in this collection of 34, there are far too many middling ones, and more than a couple bad ones. One story in particular is almost offensive in its belief of its own cleverness. A woman, Cookie Dupree, is kidnapped and her assailants question her about her boyfriend, Henry Skrabble. They ask what TV shows he likes to watch (“Do these TV shows… include that series about the transgender family, or that show about young women in Brooklyn, or the show about hip-hop artists living in Georgia…”), whether he tells her to “read certain books that wouldn’t normally interest you,” and other such banalities, before informing a shocked Cookie that her boyfriend is “Fake Woke.” As Cookie resigns herself to the idea that Henry merely presents the persona of someone who feels guilty about his privilege, she begins to weep—and at this point, one may feel a burning urge to throw the book across the room. How interesting is it to read a cautionary tale about treating “fake woke” men the way one would, say, sexual predators? It’s not so much that it’s wrong to wonder how slippery a slope it is to be policing peoples’ “wokeness”; it’s more that the way Klosterman does it sounds like the sort of reductionist fictions that David Brooks or Bari Weiss writes. The book may as well be titled Nonfictional Fiction.