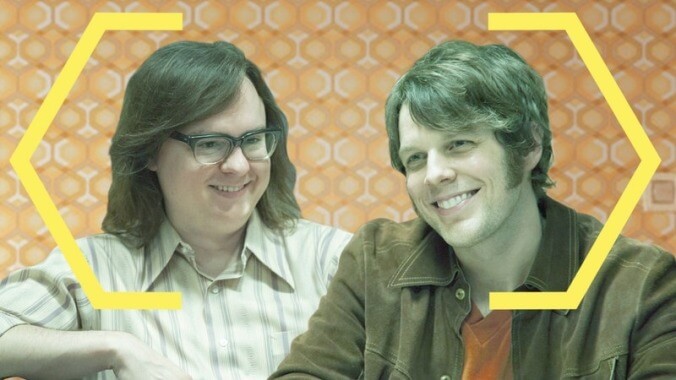

Clark Duke and Jake Lacy on the “buffet of success” in comedy and acting

When Mitzi Shore founded The Comedy Store in 1972, she established a nexus between platform and performer for up-and-coming comedians in Los Angeles. Over the years, the Comedy Store hosted David Letterman, Marc Maron, Sandra Bernhard, Margaret Cho, and the late Robin Williams, among many other notable comics. Their fellow Comedy Store alum, Jim Carrey, is one of the driving forces behind Showtime’s I’m Dying Up Here, a drama that delves into Los Angeles’ stand-up scene in the ’70s. The adaptation of William Knoedelseder’s best-selling book stars Melissa Leo as Goldie, a comedy club owner and Shore stand-in who’s every bit as brassy and badass as the original. She often acts as a mentor, but is always ready to take down her performers a peg or two if they need it.

Two of those lucky jokers are played by Clark Duke and Jake Lacy, who previously commiserated together on The Office. They star as Ron and Nick, respectively, two comedians who share ambitions but not deliveries. The A.V. Club chatted with Duke and Lacy at the Television Critics Association winter press tour about professional rivalry, trying their hand at stand-up, and balls.

You can watch the full first episode of I’m Dying Up Here for free ahead of the June 4 premiere here.

The A.V. Club: You guys have had some fun working together before on The Office. Was it just coincidence that you were reunited for I’m Dying Up Here, or is the joint participation kind of a prerequisite at this point?

Clark Duke: It’s contractual, yes.

Jake Lacy: Every third project, yeah.

CD: Every third series.

AVC: So were you guys aware of the other’s involvement?

CD: I think they told us a couple episodes in or something like that. It all blurs together.

JL: There was a while where it was like, “We’re adding a character, a person’s entering into this world.”

CD: I never heard anybody but you.

JL: Oh, okay.

CD: Yeah.

JL: Well, burn to anyone else who auditioned.

CD: Someone at some point asked me what I thought about you.

JL: And what’d you say?

CD: I said he’s the best. [Both laugh.]

JL: Bold-faced lie.

AVC: That camaraderie is present in the first couple episodes of I’m Dying Up Here, but there’s also a real competitive streak throughout. Had you guys ever encountered that before?

CD: Well, we’re not stand-ups.

AVC: Sure, but acting’s competitive, too.

CD: Not in the same way, though, I feel like.

JL: My experience with that is that like, look, most of the time, I go out for roles that a dozen other guys who look like me are probably also going out for, because some number of stars—

CD: Or Chris Pratt was busy.

JL: Exactly. They’ve said no, right? But like, amongst those 12 guys, you kind of root for each, and there might be one guy who has some ego thing that everybody else is aware of and you’re like, “get out of here.”

CD: I think it’s also, there’s so much like—when you’re auditioning for something, and I feel this way from directing stuff, and having to be on the other side of it. Sometimes, you’re just going for a look, or a feel for a person, and it really doesn’t even have that much to do with how good of a job they did or didn’t do. And for stand-up, it’s really not that. If you’re up on stage, and they’re not laughing, it’s your fault. It’s all you. But you can kind of qualify a lot of auditions on a lot of different stuff, and stand-up is not that. There’s just the one thing.

JL: There’s also, my impression of it is that like, there is no one, in our world, there’s Carson, right? Who’s giving you this okay, basically, who’s giving you validation to be like, “you’re legit.” But there really is no other version of that in the comedy world, and so there’s things, there’s gimmicky, hacky stuff that will get laughs from people who don’t know any better that comics see as hacky bullshit. Maybe it’s ego, maybe it’s competition, but also a judgment in being like, “that’s cheap.” That’s so cheap to do that hacky stuff in here, when we’re all trying to be above that, when we’re all trying to elevate ourselves, and you’re going for this easy laugh. I think within that world, comics having respect for one another is ultimately the greatest sign of validation that you can have.

AVC: You both play comedians who are a part of Los Angeles’ famous stand-up scene in the ’70s. Did you try develop your own style or material?

CD: There isn’t as much stand-up in the show as people might think, especially if they haven’t seen it. It’s more about the characters. It’s not really about their material so much. I mean, there is stand-up in the show, but not to the extent that I really had to figure—and again, my guy is a young guy starting out, and he’s supposed to be kind of shitty, frankly. But that question kind of keeps coming up, and I feel like I didn’t dig that deep into that, almost. That seemed secondary in importance as far as all the character stuff.

JL: For me, it was an awareness that Nick Beverly, who I play, comes in partway through the season, and I think you see his struggle between the material being confessional, being true and pure and honest to who he is, and how to make that into something that gets laughs. Throughout, you watch him bump up against commercial laughter or TV jokes or what’s PC at the time, and not even in the social sense, but just what’s allowed on television. What can you say on stage? And for me, there’s a personal tether between his personal life, personal acceptance, and the material that he brings out on stage.

That—to relate back into the show—is part of what was transitioning at this time as far as comedy on the whole, is that like coming out the ’50s in particular, but even the ’60s, there’s sort of set-up, punchline, set-up, punchline. Into the ’70s, there’s narrative, there’s confessional, there’s people spilling their shit, there’s people talking about their childhoods. It starts to get a little grittier and a little messier and not for everyone, but just that that wing of comedy starts to open up, and that for me, that’s where Nick resides, in that push to open into that.

CD: I also just didn’t want to feel like I was doing an impression of anyone. At first, I was like, well, okay, if this guy is however old he is, 25, in 1973, was he listening to Lenny Bruce, or Woody Allen? Or was he listening to something even older than that? Since I have no stand-up background, I was just like, I should not overthink it, and just do what they write. I feel like whatever my style is will present itself.

JL: You had said that you were going to do, you wanted to do sort of, what if Ernest had been in the ’70s?

AVC: Like Ernest Goes To Open Mic NIght?

CD: Yeah, and I kept bringing props in.

JL: Like he stole your act.

CD: Jim Varney stole from me.

JL: You’re the O.G. Ernest. But we didn’t go too deep into that.

CD: That’s a lot of subtext from me as an actor.

AVC: Maybe that’s season two. But had you guys tried stand-up before signing on?

CD: Watched a lot, wrote a lot. Did some at my house just with a microphone and a little amp, but I have not gone up yet.

JL: You bought a full amplifier set-up?

CD: I had all the set-up.

JL: You were like, two-day rental.

CD: It’s a terrible deal, renting an amp. You can buy one way cheaper at Guitar Center.

JL: I did some stand-up in Texas once, which was the first time I’d ever done it. It was one of the greatest experiences of my life. It was so cool. It really was.

CD: But it wasn’t for the show.

JL: No, no. This was years before. It was just something I’d always wanted to do. I was shooting a movie down there, and the producers of the movie would rent out this little improv theater every Sunday.

AVC: What was the movie?

JL: It started out as Intramural and wound up being released as Balls Out.

CD: Nice.

JL: Cool name change.

CD: Was that straight to laser?

JL: Pretty much. The working experience on that movie was amazing. Those guys [cast members Nikki Reed, Kate McKinnon, Beck Bennett, Brian McElhaney] were the best; I had the greatest time. But it was an experience in seeing how the cover [art] went from a football, because it’s about intramural football, to a football being held next to a CGI girl’s butt.

CD: It’s not even a real girl.

JL: No. First of all, there’s no girl’s butts, and there’s no balls that come out.

CD: But you got to get my attention at Wal-Mart, you know?

JL: I just imagine people watching it and being like, “This is a funny movie, but not at all the type of funny I thought I was buying.” Anyway.

CD: Who’s above the title on that? Stephen Dorff, Brendan Fraser?

JL: “Dorff is Balls Out.” But, yeah, [the cast] would rent out this improv, and the people there were like, “Hey, if ever you were going to do stand-up, this is the spot to do it, because it’s just like the cast and crew here.” And so I did.

AVC: But it didn’t really go anywhere beyond that?

JL: Well, yeah, I hadn’t done it thinking, “This will be my life now.” Like, I was remaining an actor.

AVC: You were just that confident in Balls Out.

JL: Obviously. But for the show, I did try an open mic with the material that was written for my character, which was a poor idea, mostly because the material and cadence from 1973 doesn’t hold up at the open mic in 2016.

CD: A lot of Watergate jokes that didn’t translate at all.

JL: It’s strange, at these open mics, you want to see someone have a singular thought, a singular line that opens this idea that then you can kind of move through. Whereas it feels like the material that we were doing or maybe that was written at the time was precise like a one-man show would be, that you would see at a live theater. There was less riffing in that, as much as like, the way you listen to a [George] Carlin album, and it’s like, “You’ve worked every word of this out.”

CD: I think a lot of people have worked out every word of a lot of the stuff out, though.

JL: I’m not saying guys who are truly going up and working at these open mics. That someone has an idea and sort of builds off of that.

CD: Kind of workshop it.

JL: Yeah. But if you’re going up at The Store and you’ve got five minutes, that’s five worked-out minutes for sure. That’s not, “I guess I’m going to talk about sneakers.” You’ve worked out your shit.

CD: I’ve seen a lot of guys pop in and do stuff where they’re like, “I’m working on stuff,” and they have note cards, and they’re trying stuff.

JL: Those guys have to be pretty big to like roll up and bump someone.

AVC: Well, speaking of that, the show is based on a book about the Comedy Store and its founder, Mitzi Shore, who Melissa Leo’s basically playing. Shore was known for being hard as nails, but she also really pushed to make room for female comedians, and even created a separate showcase for Latinx comedians. Is that something that comes up in the show at all?

JL: Definitely.

CD: Yeah, especially the female comic stuff.

JL: Yeah, and you know, there’s an argument to be made for that—yes, it’s amazing that [Shore], or even that within our show, there’s a space created for other voices. But there is also an argument to be made saying that is separate but equal, and that’s still the issue. Why aren’t they all included or given the same consideration?

AVC: Yeah, and why even bother saying “women comics” and not just “comics”?

JL: Yeah, or if you put [the show on] in a basement, or set it for a 2 p.m. time, that sort of thing where, how is that not just segregating a group of people off into the corner and saying, because you’re all Mexican, you must all do Mexican jokes, so we’ll do a Mexican hour. By spinning it off, could it potentially be as bad as silencing that voice? The show goes into that.

CD: That’s big in the show. And it’s smarter and more interesting that [the characters] are more like archetypes, because you can tell more stories and you’re not beholden to the reality of somebody’s life.

AVC: You said competitiveness isn’t really a huge deal in the show, but has it been in real life for you? That is, have you ever gotten career advice from somebody, and you just knew that they were trying to sink you?

JL: Before answering, I just want to say that there is a competitiveness in that these people pick each other apart all the time. These characters just rip on each other, but as a way of loving each other. There is a competition in wanting to succeed or feeling like you’re not getting your fair share when somebody else seems to pop off out of nowhere, but I don’t think there’s a competitiveness in the way that you wish ill toward someone, where you’re like, “I hope that guy doesn’t make it.” I don’t think there’s that.

AVC: But in the show, Andrew Santino’s character, Bill, says at one point that—

JL: I hope Santino doesn’t make it.

CD: On the record. Jake wants that on the record.

JL: On the record. Santino, no.

CD: Hard pass.

AVC: Bill says that as excited as you might be to see your friend called over to the couch, it kills you to see that, because that kind of lowers your odds.

CD: I don’t feel like that exists with actors as much. I’ve always kind of felt like your only competition is yourself.

JL: When I started acting, I was under the impression that there was a finite amount of success in this world, and that if somebody I competed against got some of that, it meant that the odds on my succeeding were now dwindling. But the pie’s endless. There’s pie for everyone.

CD: It’s a buffet.

JL: That’s right. It’s a buffet!

AVC: So would you ever undercut or sabotage someone, professionally?

JL: Never! Never! Oh my god, never! I’m the last dude. You know what, I’m the guy—

CD: Jake, you’re a monster, right?

JL: No. I’m trying to think if I’ve ever… I know a guy who would audition a lot and come into a room where there’s a dozen guys waiting to go in an audition and would talk to everybody and say what’s up.

CD: That’s the worst.

JL: Honestly, I think he’s smart enough that he kind of knew that would throw people off. Because you can’t just sit and focus. But it’s like, look, if you want to hang out, let’s get a coffee after. But I didn’t come to this audition to chit chat, I came to get a job. So fugg off.

CD: I was just thinking how that’s going to be spelled in print.

JL: It’s f-u-g-o-v.