May is unofficial “abduction month” on Lifetime. There are three different stories about kidnapped women premiering on the erstwhile “television for women” network in May: Cleveland Abduction, Kidnapped: The Hannah Anderson Story, and Stockholm, Pennsylvania. As Katie Rife recently pointed out, the narrative of these films is a staple of TV movies, on Lifetime and elsewhere: First the story captures our attention. Retrieval of the victims becomes a major media events. Books by survivors becomes bestsellers—as do fictional accounts, like Emma Donoghue’s novel Room. Abductions are so rare and salacious that we become obsessed with the outcome, and the stories become perfect fodder for the television movie format.

Cleveland Abduction largely tells the story of Michelle Knight (Taryn Manning), a struggling single mom imprisoned for a decade with Amanda Berry (Samantha Droke) and Gine DeJesus (Katie Sarife). Unlike DeJesus and Berry, Knight had no one looking for her: Her mother had assumed she had run away, leaving behind a young son.

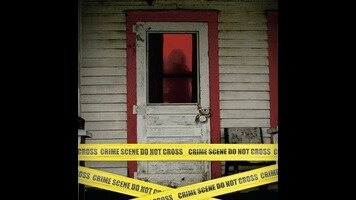

Cleveland Abduction is exceptionally brutal for a Lifetime movie, with gruesomely detailed depictions of the women’s assault at the hands of their captor, school-bus driver Ariel Castro (Raymond Cruz). Lifetime has adapted these stories as a means of elevated horror for its targeted female audience, and though it has tried to class up its image (Stockholm, Pennsylvania debuted at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival), stories featuring violence against women will always be a major draw for the network. Involving violence, sexual assault, torture, and, above all, captivity, abduction stories are a catch-all for the women-in-peril narrative that is the core theme of so many Lifetime movies.

Victims of sexual assault and similar traumas talk about how their identity and agency are taken away from them as a result of their attacks. Those psychological scars, as horrific and debilitating as they are, are largely inward. But in dramatizations of captivity, that loss of agency and identity is writ large: The women in these stories literally have their lives taken away from them. We’re not just hearing about their losses, we’re watching them happen over and over again. It’s the ultimate body horror compounded with the ultimate psychological horror in a feedback loop that doesn’t end until Amanda Berry attracts the attention of a neighbor. These stories are showing, not simply telling, the terror that can be visited upon a woman, lending themselves to the hyper-dramatic template of the Lifetime movie.

In Michelle Knight’s case, she was forced to disappear. In the film, and through Knight’s own words, she relays how Castro repeatedly told her she was nothing because no one was looking for her. Knight, who was given access to TV, watches news stories of Berry and DeJesus’ parents pleading for the return of their missing daughters, whereas Knight’s mother never appears in a newscast. When Berry’s mother dies, a reporter refers to the congenital heart failure that causes her death as “dying of a broken heart.” After the three women escape, Knight recalls how Berry’s mother kept her room exactly as it was before she was abducted. Knight’s mother, assuming her daughter had left home, moved to Florida. It’s one of the more heartbreaking aspects of Cleveland Abduction, although that feeling of isolation is largely psychological. That’s harder to illustrate than, say, Castro chaining his victims up.

That overarching violence perpetrated against these three women is the takeaway from Cleveland Abduction. What Knight endured is vividly portrayed, from being hogtied for days and suspended in the air, to beatings and sexual assault. There is truth to these scenes: Knight, Berry, and DeJesus endured these horrors and survived. But that’s also where the inherent salaciousness of these stories comes into play. These scenes of violence are depicted because what we’re watching is based on true events, but their purpose overall is to be taboo, to viscerally scare the audience even further. It’s torture porn—but this isn’t Saw, because these things actually happened.

But there’s another aspect of Cleveland Abduction, and the kidnapping narrative that makes its way to TV, that makes it perfect for its medium and its channel: There’s a happy ending. These women make it out. They are freed. They get to return to their lives, or in the case of Michelle Knight, create new ones. In the end, abduction narratives turn into redemption narratives. Granted, movies like Cleveland Abduction don’t typically show the after-effects of what these women will continue to deal with after they are released. (That’s where Stockholm, Pennsylvania starts, as Saoirse Ronan’s Leia is returned home to her parents after she was kidnapped as a baby, much like the protagonist of MTV’s Finding Carter). Cleveland Abduction’s ending seems particularly truncated, with the likes of Pam Grier and Joe Morton showing up to ultimately do very little.

Don’t blame Lifetime: Outlets like People magazine—which recently profiled DeJesus and Berry ahead of the release of their memoir, Hope: A Memoir Of Survival—tend to gloss over the painful parts of recovery as well. What matters is that DeJesus, Berry, and Knight get to reclaim their identities and their agency. Even Netflix’s Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt uses this as the thrust for its story. Kimmy Schmidt’s post-”mole woman” adventures in New York are a purposely sunny version of a post-abduction life, but every episode features Kimmy taking back her self, much like Cleveland Abduction. The movie ends with the real testimony Michelle Knight gave at Ariel Castro’s sentencing hearing:

You took 11 years of my life away, and now I’ve got it back. I spent 11 years in hell, and now your hell is just beginning. From this moment on, I will not let you define me or affect who I am. I will live on, you will die a little every day as you think about the 11 years and atrocities you inflicted on us. After 11 years, I’m finally being heard. And it’s liberating.

Michelle Knight may deal with this trauma for the rest of her life, but in terms of her Lifetime story, she is finally free.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)