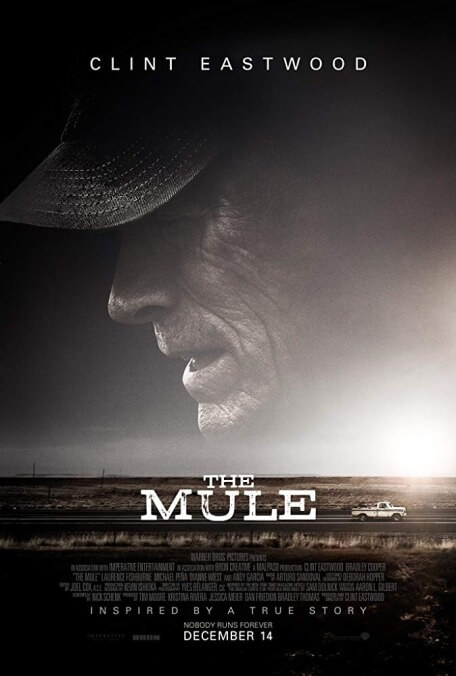

Clint Eastwood re-emerges from retirement for one last drug run in The Mule

In the 10 years since Clint Eastwood last starred in one of his own films, the de facto movie-star farewell Gran Torino, he’s embarked upon one of the most adventurous, experimental, and prolific periods of his directing career. (He also made another, less effective movie-star farewell, directed by his longtime producer and assistant director.) Unfortunately, this period has also produced some of his weakest movies, a first-take tour through both recent and mid-20th-century American history that often feels like an absentminded version of his best work. This unevenness might have to do with his semi-retirement from acting. Although he’s done well with other (professional) actors, Eastwood’s relaxed, unfussy directorial style is, unsurprisingly, a perfect fit for his tenser but similarly unfussy acting style. That’s more than evident in his newest movie-star farewell, The Mule. (Look for a 98-year-old Eastwood to say goodbye once again in an as-yet-untitled December 2028 feature.)

Eastwood isn’t necessarily an obvious choice to play Earl Stone, a flinty Korean War veteran who prizes his flower business and the accompanying horticultural hobnobbing, estranging him from his ex-wife, Mary (Dianne Wiest), and daughter, Iris (Alison Eastwood, Clint’s real-life daughter). Earl is based on a real-life figure, though loosely enough to warrant a full name change, and while his crankiness and racism seem customized for Eastwood, his glad-handing and ne’er-do-well charm feels more like Paul Newman or later-period Robert Redford. Even golden boy Redford tends to appear a little more rascally at the outset; it takes a little while to realize that Earl’s amusingly genteel interest in going to horticulturalist awards dinners is supposed to be cruelly neglectful to his family.

Facing hard times in his business (“Damn you, internet!” is not an exact line of dialogue, but nearly so) and his promise to help pay for the wedding of his granddaughter (Taissa Farmiga), Earl parlays his love of the American road into an unlikely gig delivering drugs for a powerful cartel. The job is simple: He pulls his beaten-up pick-up truck into a tire-store front, lets some cartel guys place a package in his covered flatbed, takes various scenic routes across various states, and parks his vehicle in a motel lot, where drugs are picked up and he receives an envelope of cash. Soon he’s paying for a nicer truck, the open bar at his granddaughter’s wedding, and in a particularly senior-friendly version of living large, the salvation of his local VFW and their raucous polka nights.

Once Earl gets started in the drug business, Eastwood starts cutting between his laid-back missions and the efforts of two DEA guys (Bradley Cooper and Michael Peña) to bust the cartel’s mule, who they don’t realize is an eightysomething texting novice who vexes some of his handlers with unscheduled detours for pulled-pork sandwiches. At one point, Cooper and Eastwood have an encounter in a coffee shop that’s not unlike the early-bird-special version of the diner scene in Heat.

Enough has changed culturally in a decade that Eastwood’s character joshing around with Latino drug dealers or casually referring to a black couple as “negroes” will be received less warmly than the grizzled bridge-building of Gran Torino; as in that movie, minority-populated gangs loom menacingly, not quite counterbalanced by some friendly nonwhite faces. But while this material is not always handled gracefully, the cartel guys are also ultimately not the real villains of the piece, as The Mule zeroes in on Earl’s late-breaking attempts to make things right with his family, more so than crime-picture showdowns. (Eastwood’s rapport with the lower-level cartel members is genuine, even warm, though it does imply that the true measure of a person’s worth is whether they feel comfortable bantering with a Clint Eastwood character or not.) If the drug dealers are caricatures, so too is Earl’s standoffish daughter, as poor Alison Eastwood has to swing from seething anger to affection in a matter of moments, with little humanity in between.

The movie also isn’t uncritical of Earl’s racism, though Eastwood naturally saves both his ire and his sympathy for race-related incidents that don’t directly involve Earl’s prejudices, like the mean cop who gets in the faces of Earl’s handlers for no real reason, or the brown-skinned character whose truck is mistaken for Earl’s. As he frantically explains to cops that “statistically, this is the most dangerous five minutes of my life,” Eastwood treats his fear with respect, a faint but appreciable echo of his ’90s movies like A Perfect World that consider the costs of both assumptions and violence.

The Mule is not quite A Perfect World. Like that 1993 film, it finds Eastwood performing (both as actor and director) in two of his most comfortable modes: ambling low-key pulp and quiet regretful elegy. He’s merged these interests plenty of other times, and in some ways, The Mule represents a late-period version of classic Eastwood, in that it’s even pokier and more workmanlike than his best work, and sometimes downright strange. The broader bits that used to jut out once or twice a movie, like the caricatured white-trash family in Million Dollar Baby, are more frequent, and thanks to Earl’s time at a drug dealer’s lavish party, this elegiac Clint Eastwood drama also has a lot of lingering shots of women’s butts. Yet Eastwood treats his own star persona with even more relaxed grace than usual, allowing the film to catch him singing along to the car radio or doing Jimmy Stewart impressions both intentional and not. There’s still star ego on display, but Eastwood allows it to fall away for a quietly effective ending. Whether it actually closes the curtain on his acting career or not, his trademark unfussiness has briefly become an advantage again.