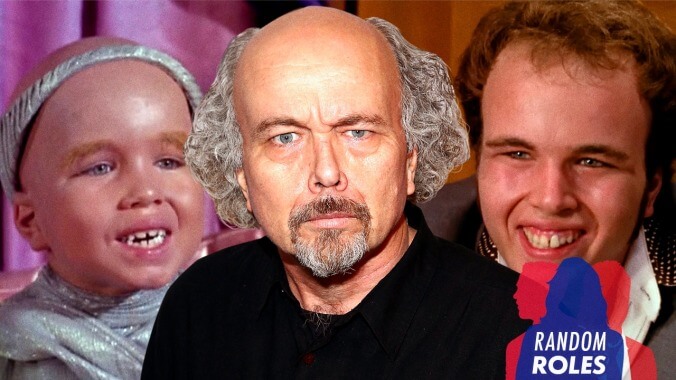

Clint Howard on working with the Ramones, a hungry bear, and big brother Ron

From Andy Griffith to a possible Ice Cream Man sequel, Clint Howard takes us through his six decades in show business

Image: Graphic: Karl Gustafson

The actor: Celebrating 60 years in show business this year, Clint Howard has more than 250 roles under his belt. The textbook example of a “that guy,” a character actor, a guest star, a child star, and just about any other Hollywood label you can throw on him, Howard has seen it all, done it all, and lived to tell the tale.

And that’s before getting into the family of it all. Along with his brother, Ron Howard, the blockbuster filmmaker who’s been Clint’s director almost as long as he’s been Clint’s sibling, the Howard brothers are spilling the beans in a new dual memoir, The Boys: A Memoir Of Hollywood And Family.

The Howards were raised on backlots and soundstages, with their father, actor and filmmaker Rance Howard, and mother, actor Jean Speegle Howard, shepherding them from the set of The Andy Griffith Show to the backwoods of Florida for series like Gentle Ben. Though frequently intersecting, their paths were very different, as Clint’s filmography can attest. Before The Boys’ release, The A.V. Club chatted with Clint over Zoom about the roles, big and small, that make up his long and storied career.

The A.V. Club: On your IMDB page, your first credit is for The Courtship Of Eddie’s Father as “Child Party Guest” in 1963, but your first appearance on Andy Griffith is 1962. Do you remember your first on-screen appearance?

Clint Howard: I don’t remember. What I remember are the conversations and the talks with Mom and Dad about all this, but I do not remember when I started in the entertainment business. I really tell people that I’m getting ready to have 60 years in the business. December of 1961 was my first day of employment and that was The Andy Griffith Show. Then, soon after, I worked on Courtship Of Eddie’s Father, which, by the way, here’s an anecdote: Liza Minnelli was the party choreographer.

These are all stories that my dad said. Vincente Minnelli directed the movie, and when it came time to do that party scene, he brought his daughter in. Liza was, like, 12 years old at the time, and Liza coordinated all the extras and did what extra coordinators do. I don’t know how much hands-on she had with me. I was still pretty much a babe-in-arms.

I really start having memories in show business at about the age of 5, so like I tell people, I’ve been paying attention for about 55 years and have actually been in the business for 60.

AVC: You have such a reveal as your first appearance as Little Leon on Andy Griffith. The camera’s pushing in and the crowd is moving away and there you are. What’s it like watching something like that from a distance?

CH: Well, boy, I was a cute kid. First and foremost, I can see why I continued to work because the camera obviously liked me. And also, the director, Bob Jones, who invented that first bit, he was a regular director on The Andy Griffith Show, he was the one that spotted me one day and said, “He’s too cute.” Because I would come to the set with Mom. Dad was working on something of his own. Mom would have to come down and watch Ron, and at the time, not wanting to hire a babysitter, Mom just brought me along, and I would wear my little cowboy outfit. Bob Sweeney saw me one day and said, “We’ve got to use him. There’s a bit we can do.” And it was that bit in the square dance, and then there was me, and I was leaning up against the door jam checking out the ladies and smiling—had a big smile on my face—and the bit worked really good.

The one thing if you really notice, and it’s something that I did a few years ago when I realized the technology to slow it down frame by frame, you can see that it wasn’t my first take because, if you notice, I blink. I tighten up a little bit as the man puts his hands over my eyes, so it’s one of those actor’s dilemmas, where if you do something a couple of times, your body gets used to it. But I held in there pretty good.

CH: I don’t have memories of working on that one, but I do have memories the next year or so. It must’ve been about 1965 when we did the recording for the soundtrack of The Jungle Book. I do remember that, and the reason why I remember that is because Walt Disney came into the recording stage and I could see him, and—I will never forget—I saw his silhouette cross in the engineer’s booth.

Of course, I was a Disney baby. I knew him by seeing Wonderful World Of Disney. I knew what Walt Disney looked like. I saw this gentleman had walked into the engineer’s booth and my eyes were fixed on him, and in a second or two, he came to the soundstage door. Back in those days, they had a little window that you could peer in to see if there was any activity. Well, I could see Walt’s eyes in the little window of the studio door, and he opened the door. He took about three steps into the recording stage, and he waved to me, “You’re doing a good job, Clint.” I was actually at the grand piano. They were trying to get me to do “The Marching Song.” I was completely mesmerized by Walt. That left an impression. That is something I’ll never forget.

AVC: He just had an energy about him.

CH: He looked like Walt Disney! You know, I remember his suit and everything. He didn’t look schleppy. He looked like Walt Disney, and he gave me that wave. “You’re doing a fine job, Clint.”

Later on in my life, I got to fly in Walt’s private plane, The Mickey Mouse. Ron and I had done a movie for Disney after Walt died [The Wild Country], and they still had the plane. We did it up in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and after 10 or 12 weeks of working in Wyoming, we flew home and they invited us to fly home on The Mickey Mouse.

CH: First of all, I remember getting tested for the skull cap. I did not want to shave my head. I thought that would be a real sign of something bad, like going to public school if I showed up to school with a shaved head. So they honored our request to test for the skull cap. And I went in for a day of testing. The skull cap worked just fine.

The costume that they made for me, it didn’t really fit. It was scratchy. They didn’t bother putting any liner or anything, and it was a sequined material, and it was itchy and scratchy. That, I didn’t dig. But one wonderful moment that I’ll never forget was my scene being shot on a set that they had built on one corner of the soundstage—I was done with studio school—and they brought me to that set while they were still filming on the other side of the soundstage. So I was waiting, and I knew the way that the business worked. There was one bell that meant they’re rolling. When two bells sound, that means that they’re not rolling anymore. And when I heard the two bells, which meant that they were done with that shot, they were gonna come towards me.

I saw some of the actors and some of the crew come out from the shadows of the backstage of the soundstage and walk toward me, and it was a really empowering moment. I wasn’t getting arrogant or anything. I knew I was prepared. One thing that Dad was really brilliant about was having Ron and I fully prepared. I never felt intimidated. I never felt like I was less than.

In many cases—it wasn’t on Star Trek, I don’t recall having any issues with any of the actors—but I do recall when I was very little, me identifying actors that were stiff. Boy, I must’ve been an arrogant little kid when I was that age to think that Lorne Greene was a little cheesy. God bless him. He was fine. That was another episode I was really proud of was my episode of Bonanza, which I did right before I did Star Trek.

AVC: The Star Trek experience was one of several episodic television shows you did that year: The Virginian. Gunsmoke. As you said, Bonanza.

CH: Please Don’t Eat The Daisies. I did all the Westerns. Years later, I did The Streets Of San Francisco. I did two episodes of The Fugitive. I did an episode of F.B.I. In writing [The Boys], Ron and I went back—because we never talked shop at home.

Listen, I didn’t hardly know what he was doing. He would go off and work. I didn’t care. I was waiting for him to come home so we could play wiffle ball or something. But he had done episodes of F.B.I. He had done episodes of The Twilight Zone. I had done an episode of Night Gallery.

We both appeared in a couple of things together. We appeared in an episode of The Danny Kaye Show together, which is a fun highlight for us. We never worked together on The Andy Griffith Show. We worked together on that movie that I referenced, The Wild Country. That was later on, I was 12 years old and he was 17, or I was 11 and he was 16. And then he did a couple episodes of Gentle Ben.

CH: Whenever they would take time off from The Andy Griffith Show, Mom and Ron would jump on a plane and fly down to Florida, and [producer] Ivan Tors, he recognized that. He was the producer, and they immediately wrote episodes that Ron could be in.

AVC: While we’re on the subject of Gentle Ben, what was it like working with a bear? If the show were made today, the bear would be CGI, but you can see that chain around your waist. That’s no computer-generated bear.

CH: No, it wasn’t. No computer can generate that smell! He was always sweating. It was a black bear living in Florida, and he weighed 650 pounds and ate prodigiously. They had to keep weight on him. So he just sat around, made some prodigious dumps, and smelled just awful.

And, you know what, he was a vegetarian. Californian black bears would eat meat if they had to, they would eat fish if they had to. But primarily they were foragers. They showed me right away that he wasn’t interested in me as a meal. And he was always based on treats. They kept him a little hungry, so he would always respond to anyone that had a cookie. That’s how they would get him to follow me around: They would put some cookies in my pockets or some honey on my right ear and the bear would nuzzle up to me all the time.

I felt no fear ever with the bear. Also, we had some great animal trainers. Bear wranglers. There was one guy named Vern Debord. There was a guy named Monte Cox. They were all there to offer me protection—I didn’t need protection.

They were also there to move the bear around. We were doing 10 pages a day, and when you’ve got a big bear like that, he’s not always cooperative. And when it comes down to say a bunch of dialogue and the bear’s doing this [waves arms around] because that’s how bears cool themselves off. Here I was, 7, 8, 9 years old, and I had to do dialogue, and this bear is just making a lot of racket. I literally had to yank him by his chain and say, “Stop it, Ben. Knock it off!”

AVC: You really didn’t feel fear.

CH: No! No, I didn’t. There were other animals that you were supposed to have a healthy fear about. Like any time you work with big cats. There’s nothing they can really do with a panther or a cougar or a lion. They’re dangerous, you know? And the extra artillery came out.

I had a slight issue with the raccoon one time, and it had nothing to do with him being mean to me. But it was a scene in which my pet raccoon, Charlie, was supposed to come to me, and I was supposed to pick him up. Well, after we did the take two or three times, he started to get really used to this behavior, and in fact, I had cookies in my pocket, which was the end result treat. I’d pick him up, and he’d have cookies to pull out. He realized where those cookies were, and we finally did a take where he didn’t bother waiting for me to pick him up. He climbed me. They did not take the claws out of the raccoon because the raccoons would use their claws to eat, and when this raccoon climbed up my pants and tore into my cotton shirt to get to me, the day’s work was over for me. I had to go to the emergency room. I had scratches up my leg.

Show business. I had already been versed in show business.

The next day, the wardrobe lady made me this inside leather vest, so under my shirt, I would wear this leather vest, and she thought it was the cutest thing. It worked out great, and sure enough, it was going to keep this from happening. I questioned, “How come you guys didn’t think of this before?!?”

AVC: Let’s jump ahead to your Roger Corman movies: Eat My Dust, Grand Theft Auto, and my personal favorite Rock ’N’ Roll High School. Grand Theft Auto was the first time that you were working on a big movie with your brother as a director, right?

CH: Well, that was his first directing job, Grand Theft Auto. That’s how he broke into the business. Roger allowed him to direct a movie he would star in too. Eat My Dust was the first one, and Charles Griffith directed it. Then Ron got a chance to direct Grand Theft Auto. He wrote the script with my dad. My dad was in it. It was a family affair. It was a great experience.

AVC: You also had a bunch of Happy Days people in there, too: Marion Ross, Garry Marshall. And you also had Allan Arkush, who would direct Rock ’N’ Roll High School.

CH: Well, Allan Arkush was the second unit director on Grand Theft Auto.

AVC: Is that how you two met?

CH: Yeah, six months after we did Grand Theft Auto, he called me and said, “I’m doing this movie called Rock ’N’ Roll High School, and there’s this wonderful character that I’d like you to consider playing.” At this point in my life, you give me an offer, and I’d do it. I knew Roger didn’t pay, but it didn’t matter. It was a good role. I liked the script.

Allan Arkush was so afraid that Roger was going to say no to his idea that he had another script written called Disco High. Saturday Night Fever had come out and been a big wildly successful movie, and the disco craze was fully enveloping the world, and so Alan was smart enough to say, “We’re gonna make a movie called Disco High.” Of course, Roger is going to like that. So once they green-lit it, they sort of changed it to Rock ’N’ Roll High School because Alan’s love was rock ’n’ roll.

AVC: What was it like working around the Ramones?

CH: It was really cool. I wasn’t really a Ramones fan. I didn’t have anything against the Ramones.

One little side note: Cheap Trick had been offered the parts in Rock ’N’ Roll High School, except Roger wasn’t offering them any money. In Color, their album, had broken, and they wanted $100,000 to be in the movie, and the Ramones did it all for $20,000, which is amazing. Four guys recording the music, appearing in it, showing up to L.A., you know, doing their parts. All that for $20,000? I mean, it was basically for free. Rock ’N’ Roll High School was made for about $200,000.

As much as I love Cheap Trick—I mean, I know them, I’ve always been a huge fan—there was something about the Ramones that made Rock ’N’ Roll High School really special. The cheese factor. The fact that they weren’t really good actors. You could go back and quote some of the lines: [imitating Dee Dee Ramone] “Pizza, Joey! Pizza!” I didn’t have an appreciation for that movie until about 10 or 15 years ago.

In fact, back in Scranton, Pennsylvania, they had a double feature at a drive-in, Clint Howard Night, they had Rock ’N’ Roll High School and Ice Cream Man. We sat through all of Rock ’N’ Roll High School. Didn’t quite make it through all of Ice Cream Man, but that’s another story.

AVC: We’ll get there.

CH: Rock ’N’ Roll High School had a spirit about it that Allan and Joe Dante—and there was a whole Corman team—brought. Listen, making movies is not a solo thing. Being an actor is not a solo thing. It takes a team. You’re only as good as the prop guy that gives you the good props. You’re only as good as the writers that give you the good material. The director that shapes it and channels it. You may think it’s Clint Howard doing all that stuff. Well, yeah, my face is up there on screen, but it does take a team.

AVC: The props for Eaglebauer’s office are incredible, like the charts and—

CH: And down to chains.

AVC: The little Superman chain.

CH: The Superman chain. And I remember when we picked that stuff out. The wardrobe lady had some selections, and then I chose through ’em and picked some and talked about it, and she went and got some more. That’s why it’s a very collaborative effort.

AVC: About two years later, you made a movie called Evilspeak. The tagline is “Remember that little boy you used to pick on? Well he’s a big boy now.” Is that a reference to your child acting or is that just a tagline?

CH: Listen, I think it was a story. It was a script that was written. A fellow named Eric Weston was the director and he had co-written the script with [Joseph Garofalo]. Carrie had been out, and what they were trying to do was a male version of Carrie. In fact, I was not the first choice. There were other actors that were considered to play Coopersmith, and I came in and auditioned, and Eric said I did a really good job at the audition, and they re-thought their other choices, and they landed on me. I don’t think it had anything to do with my child acting. I had a baby face, and I played that innocent guy, and I was carrying a little extra weight, so I was kind of a little chubby.

And also, too, on that movie, that was the first time I needed a hairpiece. I was 19 years old or 20 years old when that movie got made, and I had a hairpiece, you know? Of course, I tried wearing a hairpiece for about six months in the business, and it wasn’t working for me, so I decided to go au naturel.

AVC: Very ironic for the kid who played Balok, who demanded a cap because he didn’t want to shave his head.

CH: I did the [Comedy Central Roast Of William Shatner] years later. It was probably 10, 12 years ago they did this. The fellow, Joel Gallen, who was directing the roast thought of me. They said, “Well, let’s get Clint Howard in to get them to do Balok.” And by that point my hair was pretty bald, so I didn’t mind at all.

AVC: After that, you did a string of your brother’s movies: Night Shift, Splash, Cocoon, Gung-Ho, and Parenthood. Do you have any thoughts on his evolution from the other side of the camera, seeing your brother grow as a director? These were all pretty big movies at the time.

CH: Well, first of all, I had the utmost confidence that Ron could handle anything that was in front of him. I mean, I saw right away when he was 16 years old doing little short films with me and my friends that he had all the chops it was gonna take to be a director, and so I didn’t think anything was gonna be above his pay grade. And he did a bang-up job on Cocoon.

There’s a really wonderful evolution of his career. He made a couple of really good movies early on. Night Shift was really funny. Night Shift had some big laughs, and Michael Keaton was friggin’ hilarious in that.

AVC: You have a really funny scene in that movie.

CH: Well, thank you! Yeah, it was Jefferey Durkin. “You like music?” “Yeah!” [Sings “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.]

Then he tackled Splash, and that story can be mishandled in so many ways, and yet, Ron has this wonderful sensibility, this wonderful touch. I wouldn’t know how to put a label to it. It’s not Frank Capra. He directs with a lot of hope. And being an actor, he’s really an actor’s director, and I believe he’s also a character’s director. He’s not interested in the way something looks. He’s interested in the ways that characters behave. The roles that I’ve done for him, he’s given me lots of latitude to bring me to the table. I have a great relationship with him as a director.

Although, I tell you what, especially early on, there were parts in his movies that I wish I would’ve played, but it was going to be his decision, not mine. It’s his call. I’m not the casting director, he is. So you know there were a few times, and actually, the first movie that I did not appear in—a lot of people think I’m in all of them, and that’s just simply not true—but I wasn’t in Ransom. He called me, and I remember us having a conversation, and I knew he was getting ready to start casting. He said, “You know, Clint, I really need this to look East Coast. I need this to be New York, and if there was any of these guys that you could play…”

He has treated me really well as an actor, but you know I treated him really well, too, because I feel like I have delivered above and beyond, and he’s recognized that. He’s recognized that I’ve been put in a lot of situations, and I always find a good way to elevate the character and not elevate the character to where the character is bigger than he should be but just make him come to life.

There’s a trick to being an actor when you only have a few moments on screen, where your character arc is all going to happen in a minute. You’ve got to be able to give those goods, and you need it to still seem natural. It needs to be organic, but by god, you gotta get your beats in because, next thing you know, you’re going to be out of there.

CH: I was on a professional roll in the early- to mid-’90s. I had started to really find my footing as an actor, and I had confidence playing Sy. But again: team, team, team. Ed Harris is a friggin’ great acting partner. He gives a lot more than he gets. We had so much fun, and he brought my game up to a new level. Also, another thing about Apollo 13, the props, the technical advisers. It does, and I don’t mean to keep banging on this, but it does take a team.

AVC: Do you think the role in Apollo 13 led to the roles in Austin Powers and Night At The Museum? Because you’re doing this radar tech character, hunching over the computer.

CH: I’m sure it had something to do with that. But for instance, the Austin Powers movies, the fellow that directed those movies was a guy named Jay Roach. Jay and I had worked on a TV series back in 1992 called Space Rangers, where Jay had been kind of on the writing team of this television program. So Jay knew me from Space Rangers, and, of course, I did have the experience of working in Apollo 13. And also I was willing to do it. Some actors would’ve shied away from making fun of themselves.

I thought about it for two seconds when I started getting asked to sort of spoof myself. It’s a job. It pays. I’m going to give them my social security number, and they’re going to give me a paycheck, and this is what I do for a living. I feel like it’s going back to Dad’s philosophy of “take it seriously.” Even with the Austin Powers things, I didn’t make fun of being a radar operator. In Night At The Museum, I didn’t make fun of a NASA flight controller. I took the role, realized it was a comedy. I knew that I had to lean into certain situations a little differently, but go ahead and do it. And also another thing, shit, if I don’t do the job, someone else is going to.

CH: I’ve only turned down a couple of jobs in my life. Remember the original Flintstones movie with John Goodman and Rick Moranis? I got offered a role being one of their bowling buddies. I don’t know why I was feeling so self-conscious at the time, but I could not see myself in one of those fur costumes. I just did not see myself wearing one of those big stupid ties and a little funny bowling outfit or something, so I passed on that. It was probably a mistake because that movie ended up doing very well.

AVC: Well, you did end up working with a dinosaur that year. You were in Carnosaur in 1993.

CH: Another Roger Corman movie!

AVC: You’ve continued a working relationship with him?

CH: I believe it was 12 or 13 Roger Corman movies.

Yeah, I worked for Roger a lot. One story that we talked about in the book: Ron was trying to get Roger to spend a little more money on a few extra extras, and Roger said, “No, Ron, you’re not going to get anymore extras, and if you do a good job for me, you’ll never have to work for me again.” And Ron never worked for Roger again, and I did. I had a great relationship with Roger. I haven’t seen him in a few years, but a few years ago, we got together for a Rock ’N’ Roll High School tribute, and he was in great spirits. He’s about Dad’s age. He’s in his mid-90s by now. I have very fond memories of Roger.

AVC: While we’re in that horror zone, I wanted to get your thoughts on Ice Cream Man because that is a very iconic VHS box cover. I remember seeing that at Blockbuster every week.

CH: I was just trying to churn work. They called and asked for me. I went in, and I met with them, and they wanted to hire me, and I was excited. I was really excited that I was going to get to play the lead of this. I met with the director, Norman Apstein, and he was trying to do this kids horror movie, and it was kind of an interesting approach—it wasn’t all completely serious but it wasn’t all farcical. I liked that. Immediately, I got along with Norman. We’ve remained friends over the years, and in fact, we are seriously, not just contemplating, we are figuring out how we’re going to make a second Ice Cream Man.

It’s something that really excites both Norman and I. There was a time in our lives where we just didn’t mess with it. Because listen, the original Ice Cream Man’s a little spotty. If you watch it from the cinema eye, it’s a little spotty.

About 15 years ago, Norman and I got together with the idea of trying to raise some money to get a second made. Then we watched the first one and he goes, “I don’t want to do this because if we make a good Ice Cream Man 2, that means that people are going to go back and watch the first one.” But we have shed that skin.

We’ve landed on what the tone’s going to be. We’re not going to have a lot of kids in the movie. It’s going to be more of a horror film, a demented man my age, a demented ice cream man. I don’t believe it’s going to be the same character. We’re going to make a movie called Ice Cream Man starring me.

Lovely memories working on the movie. I still talk about it all the time. I still go to science fiction or horror conventions, and besides maybe Star Trek, the title that most people want to talk about is Ice Cream Man.

CH: [Laughs.] That was cool. A director named Tony Randel asked me to be in it, and I didn’t have a lot to do, but it was one of those times in my career where I needed to get paychecks and take the job. I remember that was the O.J. Simpson low-speed chase. On one night we were filming, and I’ll never forget the soundman who had a little video monitor on his sound cart, he had it flipped over to the O.J. Simpson slow-speed chase. He wasn’t even paying attention to what we were filming in Fist Of The North Star.

AVC: Did Corbin Bernsen actually scrape your teeth?

CH: Yes! Corbin Bernsen was awesome, and that was a wonderful experience. One of those collaborations that was really cool. Brian Yuzna, the director, let us do what we wanted. It was fun. A lot of improvisation. And, of course, the bullets are flying so fast in the low-budget horror genre, we were done with that scene in about three hours.

CH: Great experience. Man, made me cry when I got there and I saw that they were letting my big brother be the tip of the spear of that billion-dollar project. It made me really proud because of the way Ron was handling the crew and handling the cast. It was a collaborative effort. They were really rooting for Ron to do good, and Ron stepped in after 70-some odd days. The two guys that they ended up replacing, they had been working for 72 days or something like that. Ron called me because I was going to fly there to work, and Ron mentioned that, for him, it was the third day on the call sheet, and it was, like, day 77 for the movie.

But again, a very proud moment. And fun! I had fun doing it. I love working for Ron. I didn’t have a whole lot to do in the story, but it kept me busy, and I got a trip to London out of it.

AVC: What was going on with the BloodRayne: The Third Reich and Blubberella split production?

CH: Well, Uwe Boll—a director I’ve worked with a bunch, and I really like him—he doesn’t make the best movies in the world, but by god, he’s honest and he treats the actors well, and he’s a good man. Any time Uwe calls me, I pay attention and listen to what he has to say. He was going to do BloodRayne: Third Reich, which was the latest installment of the BloodRayne franchise, but he couldn’t do it unless he made another movie simultaneously, so he invented the idea of doing this big, heavyset woman as a superhero vampire. It was almost spontaneously invented. Michael Paré and I wrote most of our dialogue. Lindsay Hollister played the big vampire. She wrote most of her dialogue.

We shot it in Zagreb, Croatia. It took about a month to shoot two movies. There was one day that I did 18 pages of dialogue. I did, like, eight pages from one script and eight pages from another script.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.