There’s something extraordinary about how comic books depict environments. Because pages are composed of individual panels, creators have the opportunity to spotlight many different parts of a setting. These separate images come together in a layout that moves through the space, and the larger page functions as a single piece of art reinforcing the overall atmosphere by uniting all those distinct pieces. A graphic novel like Richard McGuire’s Here gains an almost mystical quality in its intricate layering of panels showing a single physical space at different points in its millennia-spanning history, building a narrative entirely around how a setting changes over time.

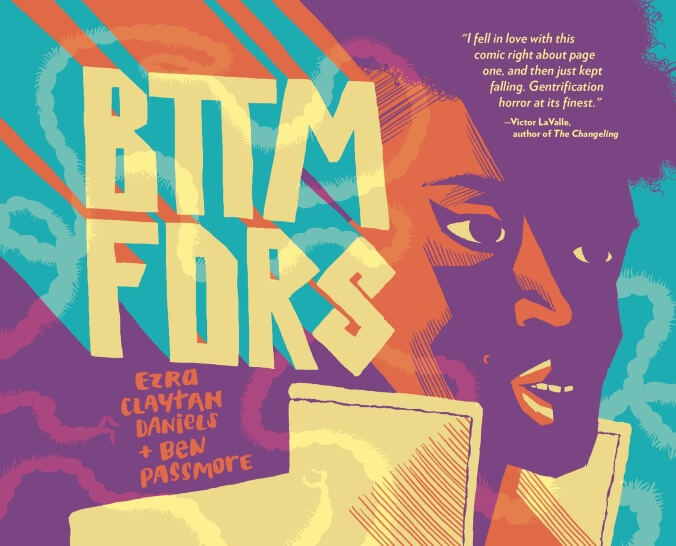

Two new graphic novels do exceptional work establishing a sense of place, taking readers into home spaces that become prisons over time. In Seth’s Clyde Fans, a poignant meditation on memory and family over 20 years in the making, the titular storefront and the domestic quarters above it have soaked up decades of resentment and disappointment from two brothers forever changed by the abandonment of their father. Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore’s BTTM FDRS is far more fantastic, telling a creepy, grotesque story about a living building in the Bottomyards, a fictional neighborhood on the south side of Chicago.

Brothers Abraham and Simon have lived in the Clyde Fans space for decades whereas Darla is just moving into her doomed Bottomyards buildings. Their stories reflect their relationships with these locations: Clyde Fans makes the home a container for bad feelings to fester, trapping inhabitants with their grievances against the world. BTTM FDRS turns the home into a living monster, making new inhabitants suffer because of past structural damage. The truth behind the horror exposes a history of marginalized people having their accomplishments exploited by an amoral authority, and future generations end up paying the price.

There’s not much overlap between these two books, but reading them together offers a fascinating comparison of how to use settings to conjure emotional reactions. The emotions in Clyde Fans mostly fall on the downer side of the spectrum; Seth establishes a lonely, somber tone from the start with a series of two-page illustrations of eerie empty rooms. Readers will become very familiar with these spaces over the course of the book, and Seth provides a comprehensive tour in the opening scene, a 64-page monologue that has an elderly Abraham musing about his past and sharing what he’s learned from his years as a salesman. He speaks confidently about his sales prowess during this speech, but when the story flashes back, his attitude at the time is much less self-assured.

After that monologue, the story jumps back 40 years to follow Abraham’s brother on a sales trip to Dominion, the fictional town that also exists as a miniature cardboard replica in Seth’s home studio. (Check out the documentary Seth’s Dominion to learn more about this.) This trip convinces the introverted, neurotic Simon that he has no future in sales, but it also leads to a moment of transcendent self-realization, presented later in the book in a surreal, poetic sequence that sends Simon’s consciousness outside of his body, traveling across a slew of locations as he realizes that his place isn’t out in the world, but inside the childhood home he’ll never escape. Simon has a more intense connection to the home than his brother, and scenes like Simon recalling every object in his mother’s room go into micro detail to emphasize how the space has left a profound mark on Simon’s mental state.

BTTM FDRS is a thrilling sci-fi horror story rather than a psychological deep dive, with plenty of humor to provide relief from the tension and endear readers to the characters. When Darla’s toilet overflows with a gory mess of blood-red viscera, she glares suspiciously at her friend who just used the bathroom. When Darla argues with her DJ neighbor about profiting from colonial practices in his art, they bury the hatchet by agreeing that white people are the enemy, and the entire bar laughs in agreement. One of those enemies is the shady landlord of their building, who bought it as an investment property and is filling it with young art students to facilitate the neighborhood’s gentrification process. Darla grew up in the Bottomyards so she has roots in the neighborhood, but as a trust fund kid, she plays a part in changing the economic demographic.

Daniels built this story around cultural appropriation in the world of hip hop, with Darla’s best friend, Cynthia, representing white artists like Iggy Azalea and Miley Cyrus who co-opt hip-hop sounds and styles when they are profitable and ditch them when they aren’t. Cynthia wears a cap with “RAP” printed on the underside of the brim, and all she does is talk shit about Darla’s new neighborhood until she finds out a trendy artist lives in her building. Darla notices how quickly Cynthia’s opinion of the Bottomyards changes once she sees how she can use it for her personal gain, leading to a fight where Darla calls Cynthia out on her privilege and Cynthia breaks down because she can’t help being white.

The building needs a pilot organism, and Cynthia literally stumbles into the role. Once the building bonds with a pilot, its functions all activate under the control of the pilot’s subconscious. Presumably, someone would be able to train themselves to have a stronger grip on the building’s nervous system, but Cynthia has no preparation before symbiosis occurs. The system ends up being run by Cynthia’s worst impulses, the ones that seek to sabotage her friend’s success and even eliminate her if necessary. The tension between friends is clear early on, with Daniels’ sharp dialogue and Passmore’s animated artwork heightening their animosity. That animosity turns into something more deadly once the building forces itself on Cynthia, and Passmore depicts the carnage with ferocious energy that sends the book’s momentum skyrocketing in the back half.

BTTM FDRS is steeped in social, political, and cultural commentary, which only becomes more pronounced as the building’s tragic history is exposed. By contrast, Clyde Fans doesn’t spend much time addressing the external world around its main characters, and when it does, the circumstances are very different depending on which brother is in the spotlight. When Abraham signs away the family business, he’s confronted by the grizzled faces of the workers he’s just put out of work, people who need employment after the recession of the early ’70s. For Simon, larger social issues come into play through pickaninny toys he acquires, symbols of the prejudiced, hateful views that are widely shared at the time. In an interview with The Comics Journal, Seth explains the significance of the pickaninny imagery:

I’m often called a nostalgist but I’m aware of the racism and misogyny of that white man’s world I’m portraying. I don’t want some golden fog of the past… Why is it that Simon goes back to his room with the racist toy instead of any of the other cheap novelties Whitey was peddling? Because the vulgar toys are a symbol of emasculation, humiliation, servitude and the loss of human dignity, something Simon is allowing to happen to himself but is also complicit in.

One of the most unsettling scenes occurs when Simon talks to a pickaninny figurine that sits on his shelf, which speaks in empty word balloons while staring intensely at nothing. Simon projects all of his insecurities onto the talking toy, and while we don’t see the words he’s hearing in his mind, his reactions reinforce this idea that the pickaninny is there to tear down Simon and make him feel unworthy. This racial commentary is one of the few places where Clyde Fans and BTTM FDRS intersect on a thematic level. While the former doesn’t focus on tools and methods of oppression like the latter, Clyde Fans acknowledges the ways that white people feed a system that keeps marginalized communities down and prevents society from making positive changes for all.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.