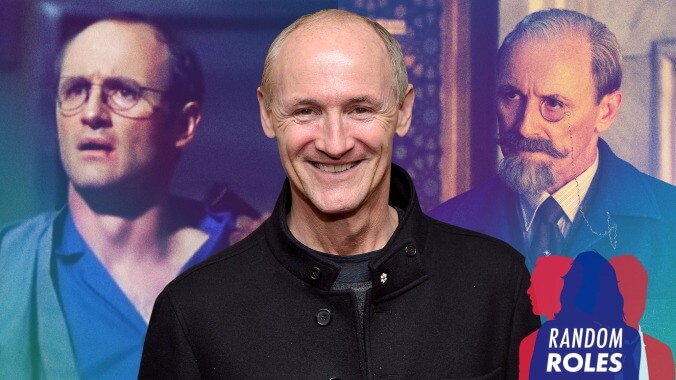

Colm Feore on fathering The Umbrella Academy and close calls on the sets of Face/Off and Iron Eagle II

Image: Graphic: Libby McGuire

The actor: Veteran character actor Colm Feore has primarily built his decades-long career on small but vital roles, like the doctor who performs the titular operation in Face/Off, or the calculating patriarch of The Umbrella Academy. Although he was born in Boston, so much of his career has been spent in Canada that most people just reasonably presume that he’s Canadian: He attended the The National Theatre School Of Canada, got his first on-camera acting job through the CBC, and has spent more hours working in Toronto and Vancouver than anyone would ever want to try and count. For 40+ years, Feore has been working steadily in film, TV, and the theater, including roles in The Chronicles Of Riddick, Thor, Stephen King’s Storm Of The Century, and the cult Canadian comedy Slings And Arrows, to name just a few. Ahead of his new action thriller Trigger Point (now in theaters and available on VOD), Feore sat down with The A.V. Club for an enlightening round of Random Roles.

A.V. Club: How did you find your way into this new project; did they reach out to you?

Colm Feore: Brad Turner, with whom I’d worked on 24 years before, was looking to hire me for this… and I didn’t know that. [Laughs.] I was busy doing theater here in Stratford, Ontario. And then in the middle of the pandemic, we got shot down, the film got pushed, and so I was suddenly available! And he said, “Well, now I’m going to do it in the fall. Would you like to come on?”

And the part’s terrific, it made great sense to me, and it wasn’t a huge stretch in terms of… Well, I mean, I could use my own hair… and everything else! And there were a lot of very nice people in it. Barry Pepper, of course, is fantastic. And Carlo Rota and Nazneen Contractor and Jayne Eastwood… I’ve known all these people for a long time.

AVC: How would you describe Elias Kane?

CF: Elias is… You know, he’s an old-soul leader of a gang of people so far undercover that they really are deep state and have told so many lies that they no longer know which way is up. It’s a very good exercise for an actor, because obviously that’s what we do for money. [Laughs.] And so there’s a moment in the film where we talk, Barry and I, about our characters not being able to tell any of our loved ones the truth about what we do, so we’re always living these double lives.

And I found that fascinating. I thought, “This is an exercise in acting on acting on acting, and who is deceiving who, if anybody is deceiving anybody! We’re just trying to get to the bottom of a mystery.” And so that’s how I threw myself into it: in a sense, wanting not to know the ending. I don’t want to know the answer. I just want to trust that when Brad says, “Do this,” I do that, and he’ll put it all together, and it’ll all make sense. It was kind of an interesting trust exercise in that sense. So when I saw the film, I was surprised.

AVC: We always try to go as far back in an actor’s onscreen catalog as we possibly can… Based on IMDb, it looks like it was playing a character named Rick in an installment of The Running Man.

CF: Holy cow! Okay, that’s only… 40 years ago or so. [Laughs.] That was kind of a breakout thing. I got that job, which was a young kid confused about his sexuality, and he’s on a track team, which was a lot of acting, because back then I was fat and slow. They shot me very strategically! That was the saddest part. But the track coach was going through the same kind of issues, and yet he couldn’t help me, so eventually I throw myself in front of a train!

But what was really key about it—and really useful for me—was that I’d come out of theater school, I’d been in to some auditions, I’d done some plays, but I wasn’t really sure about TV. So the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation would do blanket annual auditions to see all the new people, and I got one. And I went to one of my old teachers and said, “What the heck do I do to go in and show them that I’m not just a theater actor?” And Michael Mawson—a great mentor and friend—very cynically said, “Just show them a couple of moments of intensity… and a couple of moments of quandary.” I said, “What?!” He said, “Just trust me: Go in, act like you know what you’re doing… and occasionally act like you don’t!” “…Okay.” [Laughs.]

So I go to the studio, and I’ve got a speech; I think it was, if memory serves, David Rabe’s play about the Vietnam guys. Anyway, it was a really cool speech to do in, like, 1980 or whenever I did that. So I go in, and I literally do a couple of moments of intensity… and a few moments of quandary! I’m telling you, they came out of the booth, shaking my hand, and I had that job on The Running Man the next day! [Laughs.] And from that moment on, I thought, “This is a racket!”

AVC: How did you find your way into acting in the first place?

CF: You know, I’d been doing it throughout high school and even junior school, and I had just fallen into it as something to do, an extracurricular activity where you’d get checked-off marks for being engaged and agreeable… So when it came to my high school years, I was a pretty average student, but I was doing a lot of these plays. So one of the drama coaches and a literary teacher there said, “You know, you could audition for the National Theater School as well as applying to universities.” So I did that. I applied to these universities, kind of thinking I’d make a fairly middling English teacher at some high school if I was lucky. But there was nothing really outstanding about me. So I agreed with him. And he gave me some coaching, he drove me to the audition, because we were in Toronto. And then… I got in! I don’t know how, but I got into this theater school. And because people applied from across the country and very few people got in, I thought that was kind of cool and that maybe it’d be worthwhile investigating actually going.

So I called my parents to say, “Look, this is a little awkward, I know it’s not quite what you had in mind for me, but it looks like I’ve gotten into the National Theater School in Montreal, and…maybe I should do that!” And they said, “Oh! Crap! We should’ve told you! The letter of acceptance came in a week ago, and it was time-sensitive, so we’ve already accepted on your behalf!” And that was an enormously encouraging vocal support of the whole idea. You know, my dad was a doctor. An actor? No! He thought. “That’s for rogues and vagabonds! That’s not really a job!” But—God rest him—I didn’t ask him for money an awful lot in the last 43 years, so… so far, so good!

CF: Oh! Stephen King, one of my heroes. That was a particularly great get, because the character of André Linoge, with the hat and everything… [Starts to laugh as he puts his hand on his head, which is covered by a familiar-looking hat.] It’s like I haven’t really changed! God knows that was many years ago, but I liked the look of him, so I just kept it! But he was so remarkable as a creature, because he was articulate, he was intelligent, he was mysterious, and he was scary as hell.

And the thing had come straight out of Stephen, not as a novel, not as a redo of a movie, but absolutely a screenplay for television, and I think we shot his first draft. He just sat down and said [Miming the act of typing.] “I need six hours of TV, and I need 70 characters.” And there were such extraordinary people in it—Tim Daly, Casey Siemaszko—just delightful human beings and great actors, and we had an awful lot of fun doing it. And I thought it worked out very well. It’s one of those things that I can return to, or if I turn the TV on in a hotel and it’s on, I’ll actually stay and watch it, just for the old time’s sake, and it’s still scary.

And I was very pleased to get it, because I auditioned for him a year or two before when he was redoing The Shining, and I didn’t get it. But I was standing with Stephen at the producer’s house, because we’d all been flown in to audition with the leading lady—I think it was Rebecca De Mornay—so it was an awful lot of fun, and one felt very lucky to be there at all. And I remember standing there, looking out over the hills in L.A., in this producer’s magnificent backyard, with Stephen King. I’d just arrived in L.A., and I didn’t know anything, so I said, “What do you think about L.A.?” And he said, “I don’t like L.A. And the people I like, I don’t like ’em when they’re in L.A.” [Laughs.] And that was kind of the trepidation with which I faced that strange thing.

But then a couple of years later, up came Storm Of The Century, and I got the part. And I see it as a real high point. I think it was a real gamechanger for me. I don’t know if it changed my career particularly, but I felt really good about the work we all did, and it was such a lot of fun. It was a remarkable thing to be a part of.

CF: That thing’s turned out to be an absolute monster hit, particularly in the States, on the Independent Film Channel. It’s kind of modeled on the kind of repertory classical theater right around the corner from my house here at Stratford. And although the writers will claim, “No, no, no, we didn’t base it on that,” they’re all actors who’ve worked here and, in fact, Stephen Ouimette, who plays the artistic director who gets run over by a pig truck and comes back as a ghost… He stole that from Richard Monette, the actual artistic director for the Stratford. So the whole thing is an homage.

I feel a bit guilty about the show because when they asked me to do it—and the guys who were producing it, I’d done a lot of stuff for before, The Red Violin, with its Oscar-winning score, 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould, and I’d done some other work for them—and now here they were doing this thing. And they thought, “Well, we’d like you to be part of it, and because you’ve got an enormous amount of experience with Shakespeare, we thought, ‘This is a no-brainer.’” And I kind of turned my nose up at it. I said, “I don’t really want to play that part. That’s obvious.” And they foolishly said, “What do you want to play?” And I said, “Sanjay interests me!” And there was a pause, and then they went, “We’re going to have to get back with you.”

Now, the back story of this is, I’d just done a production of Coriolanus here, in which was a wonderful actor named Sanjay, who was a pal of all these guys. They’d actually written this part for him! [Laughs.] But when I said I wanted it, somebody had to call and say, “Listen, um… Sanjay, the thing is, Feore wants your part, we think he might be more of use to us… We’ll write something else, but are you cool with that?” But they didn’t change anything about the part! So that, I think, added to the spectacular weirdness of it.

So that, too, was a lucky grab. And I just threw myself into it, thinking, “This is absolutely ridiculous, but if you do it full out, you know what? It will be less ridiculous!” And there are still people who come up to me on the street and go, “Sanjay, if you wanna be an EMS person? You just get on that ambulance, and you become that person!” And again it goes back to that business of acting: You’ve just got to believe. And the more you believe, the more we believe. So is he a charlatan? I don’t know! But, of course, it used to drive [Mark] McKinney crazy, because I remember we were in prison, and I’m in a jumpsuit, and he’s going, “You’re in jail! How can you think like this? This is not right! It’s not real!” “Yeah, but it worked!” And they’re thinking of bringing it back, too. I’m hoping they’ll call!

The thing about Slings And Arrows is that is was made essentially for free. We all work for scale. And it was so successful that, after three seasons, they could hardly ask us to work for scale when they were making money. So they just went, “Okay, that’s enough.” [Laughs.]

And I got a call, actually, from the producer, Niv Fichman, because I was doing another show for him that day for his Rhombus Media… also for scale. So I did the morning for one show, Slings And Arrows, got into their little Jeep and drove across to the next show for the rest of the afternoon, also for scale. He calls me from a sushi bar in London, England, I’m in Toronto, shooting in the freezing cold. He said, “I just wanted to say how pleased we were that we’re finally able to offer you double scale!” [Laughs.] And I said, “I’m doing two different shows for you. You’re paying scale twice. That’s not double scale! And there’s twice that much in raw fish on your plate in front of you in London! Don’t try and trick me!” This is how we have to make a living.

CF: Reginald Hargreeves came kind of out of nowhere, and I don’t know what they’d seen of mine that tempted them in my direction, but it’s been a fantastic amount of fun. It was kind of a laugh to start, because my agents and managers weren’t allowed to see any of the scripts and weren’t allowed to see any of the storyline. You know, the deals were good, they were terrific, and I was grateful for the work, so I said, “Yes.” So we go along and we start, and it’s a riot to do.

Everybody in it is delightful: Robert Sheehan, an Irish actor; Tom Hopper; Elliot Page; Emmy Raver… They’re all just delightful, and we’re having a riot. And I’m mostly playing—in the first season—with their younger selves. I only see the adults once in a blue moon. But about episode seven I get a call from my managers and agents saying, “Hey, how’s it going?” I said, “It’s going very well, and I have every hope that it’ll succeed!” They said, “Oh! Any chance you’ll come back?” And I said, “I’m sorry to have to break this to you, but I don’t think so.” And they said, “Why? Does your character die or anything?” And I said, “Actually, he starts dead. Before the credits roll, he’s already dead. So I have to say that, no, I don’t think there’s any chance for me coming back.” And they slunk away, kind of dejected, and thought, “Well, that wasn’t quite what we expected…” [Laughs.] And then—lo and behold!—I get a call from [Steve] Blackman and company saying, “So! What about season two?” And I said, “Well, is this like Jesus? Is it Easter? How the heck does that happen?” And finally they had to say, “Welllllll, we’re messing with the timelines…” And I thought, “Okay, I’m in. This is fun!”

One of the great things about it is that, of course, I’m so disguised that I’d meet people in the street, and they’d say, “Oh, have you seen this thing, The Umbrella Academy? It’s fabulous!” And I say, “Yeah, I like it a lot! Particularly the old guy. You know, the mean dad? I like him very much.” “Oh, yes,” they say. “Very good!” I said, “That’s me.” “No, it’s not.” “No, no, yes, it is. I can show you a picture on my phone!” [Laughs.] And I take it as a great compliment. It’s a testament to the acting and the makeup that they have no idea… and hopefully that means that we can do other things!

CF: [Laughs.] Mind you, it got me a trip to Israel and to Egypt briefly, at the end of the shoot. And it was fantastic. Sidney Furie directed that, a Canadian director who’d achieved a considerable amount of success in L.A.; he’d done really super cool films with people like Michael Caine, like The Ipcress File, one of those wonderful spy-drama things. Super groovy. And so it was a lot of fun.

But I remember the audition, and I thought, “How am I going to do this?” They said, “Okay, well, he’s gotta be Russian.” I thought, “Russian… Who do I know that’s Russian?” And one of my favorite movies at the time was a thing with Peter Riegert and Burt Lancaster called Local Hero, a small Scottish film by Bill Forsyth—one of his trilogy with Comfort And Joy and Gregory’s Girl—and it’s a brilliant movie. Very charming, very funny. But in it, there’s a Russian actor, Christopher Rozycki, and I’ve always liked him. [Begins drifting into Russian accent.] And, you know, he’s a fisherman, and he’s been buying some fish at the village… So whatever Russian accent he had, I tried to steal, right? [Laughs.] So I stole it for the audition, and I thought, “I can fix it on the plane if I get the job, and off we’ll go.”

The trouble with the internet, if one is ever foolish enough to Google one’s self just out of sentimentality and things like Iron Eagle II pop up… [Starts to laugh.] I read somewhere, “Oh, yes, Iron Eagle II: the second in a series with Uncle Lou Gossett…” A delightful man, by the way, but I had taken it because David Suchet, a very respected Royal Shakespeare actor, was in the first one. I thought, “If it’s good enough for David Suchet, it’s good enough for me!” And we were surrounded by great classical actors: Neil Munro, Alan Scarfe, Gary Reineke, Clark Johnson, Maury Chaykin… Wonderful people and just a lot of delightful actors to be stuck in the deserts of Israel with. And foolishly, years later, I’m looking at this post… “And then there’s Colm Feore, with a ridiculous Russian accent…” And I just thought, “I’m not reading any farther. Point taken. I’m going to try and get better at this.” [Laughs.]

I remember that we got into these Israeli jets, and… I was too tall! So I get in, and the canopy comes down and bashes me on the head and squishes me down into thing. I didn’t look very cool.

Also, Lou Gossett nearly got us all killed! There we were, on my last day. Keep in mind that I’m in Israel, in the desert, somewhere between the Gaza Strip and Israel proper. We’ve taken over a great chunk of desert, and we’ve made it look like a firing range. So there’s a lot of weapons, a lot of targets, and there’s a lot of people standing around in army uniforms with guns… only I’m dressed as a Russian.

So Lou’s got a facing-off scene with all of us Israelis and Russians and a couple of Americans—actually, Canadians masquerading as Americans—not getting along, and he’s got to tell us what for and to behave like a team. And in order to get our attention, he takes the Uzis from Uri Gavriel—brilliant, the Clint Eastwood of Israel—and Mark Ivanir, another great Israeli actor, and Lou fires the weapons and fires about 30 rounds of ammunition from each of them into the air.

So Lou wants to practice this. “Let’s do a little rehearsal.” I’m, like, “Oh, geez… Okay, it’s my last day. Please don’t get me killed.” Well, he turns around and blasts straight into the sky two fully-loaded semi-automatic Uzis… just as a Cobra gunship helicopter filled with a lot of very confused Israeli soldiers who’ve just come on a refueling mission from their trip over to Gaza comes across the dune to see what the eff is going on! This Cobra gunship sees a rifle range, guys with guns, Russians… and it drops out of the sky and comes FWOOM! hovering down over us. Guys start leaning out of the window with their weapons, going, “What’s going on here?” I’m now crapping my trousers, because I’m dressed as a Russian.

Now, I thought the fact that we had some cinema klieg lights out would’ve tipped people off that there was a guy with a camera crew over there somewhere, that it wasn’t just a documentary, that we were probably pretending. But the Cobra gunship is hanging down, the guys are out of the windows… Sidney Furie, God love him… [Starts to laugh.] He turns to the first A.D. and says, “Go talk to them! We’ve got a permit! We’ve got a permit!” So the first A.D., with a radio and a piece of paper, starts walking toward the helicopter gunship full of Israeli soldiers, who are confused, and tries to explain, “We’re just makin’ a movie!” I thought, “This is the end of my career.” And, indeed, Iron Eagle II very nearly was!

CF: That was a huge milestone for me because it was essentially an art-house hit. It did things like the Venice Film Festival, the Berlin Film Festival, Toronto… And it was made for pennies. It was about the great Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, done in 32 short little pieces. It was really cool. In fact, the same guy who wrote Slings And Arrows and was in Slings And Arrows was a writer on that. Anyhow, bottom line, I’m here doing Shakespeare—I was playing Mercutio in Romeo And Juliet at the time—and he doesn’t live for the second act, so the director, François Girard, and Don McKellar, who was the writer and actor I referenced, they come to Stratford, they see me do this, and then in the second act, because I’m dead, we go out for dinner. And I try to pitch them my prep for being Glenn Gould. So I’m in a big, fuzzy sweater and cap, I wear the gloves, I’ve got the mannerisms… I try to sell these guys on my being able to play this fellow. And I succeeded, sort of.

François is a pain-in-the-ass director. We had many, many auditions. It was a grueling process. And finally he let me do the job. It wasn’t like there was any money in it, but what happened was, with that I had for the first time a clear sort of calling card. And by the time it came out on VHS or laser-disc… [Laughs.] I was still here in the theater doing stuff. And François had said to me, “You know, you could do more film and TV. The only thing is, you’ve got to be available. You can’t sit here in Stratford on your duff just being a classical actor. But you’ve got to be available.” And I said [Sounding vaguely annoyed.] “Well, how long do I have to be available to find this work?” He said, “Probably two years.” And I had obligations already. I couldn’t just wander off looking for this work. But in the end, I took him at his word.

I waited until 32 Short Films came out, something where I could buy a box of these VHS tapes or DVDs and go around to folks in New York and L.A. and say, “Do you want to see this? I’m in this.” Robert Redford programmed it about three or four times at Sundance. Sidney Lumet had seen it. Milos Forman had seen it. So suddenly I got into rooms I really never should’ve gotten into, on the strength of this. Now I realize you should never ask these guys if they’ve seen it. But I’m in these glamorous offices in L.A., and they say, “So… 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould,” and like an idiot, I’d say, “Oh, which of the films did you like best?” Only to realize that the secretary had seen it and the secretary liked it. They’d have the poster in their office, but they hadn’t seen it. They didn’t have time to see it. What was I thinking? [Laughs.] And sooner or later I learned not to care about that and just take the meeting. And that kickstarted a bunch of things.

I got auditions, I got roles… Sidney Lumet hired me a couple of times, Redford met with me and auditioned with me, and I was part of a ruse where the actor he actually hired was trying to up his fee and therefore was playing hard to get. I was just a pawn in a game! [Laughs.] But then I was making all these connections! So it turned out to be a huge help toward kickstarting something for me that otherwise I don’t think would’ve ever happened… It was a critical success, but it was the same cheap guys for whom I did Slings And Arrows, so it was still for lunch money! But in terms of its impact, it’s held up pretty well.

CF: The Caveman’s Valentine! Kasi Lemmons directing. My second picture with Samuel L. Jackson, the first being The Red Violin. I was playing photography, so I was really into photography at the time, and I still am. It was a very interesting learning curve. Sam was delightful. Kasi was fantastic. You know, it was a great murder-mystery picture, but something happened to that. It came out, and I forget what else was going on in the movies, but it kind of got buried, which was too bad. It was remarkable for having more producers than any other film in history, Danny DeVito being at least one of them. If you look at the list of producers on that, you think, “How did we have enough money to pay them all?”

But it was a terrific movie to work on, and I thought it was going to be a huge help to my career. And I’ve realized subsequently that nothing is really a huge help to my career. The only thing that you can do is keep showing up. If you get asked to work, just say “yes,” cash the check, and go home, and if the check doesn’t bounce, it’s a hit. I’ve never understood the mystery of post-production, advertising, global domination, whether it sells in Taiwan or Australia… [Waves away dismissively.] So if they’re fun for us to do, I just check them off as a fabulous experience.

AVC: And The Red Violin, that was also generally an enjoyable experience?

CF: Oh, yeah! And The Red Violin only got made because Sam agreed to do it! You know, when he said, “Yes,” suddenly a whole lot of international money fell into place. It won the Oscar for John Corigliano for the score, with Joshua Bell playing the music. I mean, just beautiful. And a beautiful film to work on because it was so fragmented. How was it going to work? Yo-Yo Ma, who was a friend of Niv Fichman, our producer, said, “Hey, I’ll get you a Stradivarius in there somewhere. I can get you this extraordinary violin. We’ll figure something out!”

You know, when you do these kinds of art films they’re for love, really, because nobody’s getting rich doing them, the work is worthwhile, and you’re with friends. I just saw a quote from Tony Hopkins, who said, “I love to work, and I like to have a bit of a laugh with it.” I’ve worked with Tony a few times, and I couldn’t agree more. If you can get some work and have a laugh doing it, what else is there?

CP: Titus was my first film with Tony Hopkins, and Thor was my second. I’d played his little brother for Julie Taymor in Titus, so when Kenneth Branagh—Sir Kenneth… and Sir Tony!—called me up to do Thor, I was absolutely delighted to be part of it. First of all, Ken was very gracious. He said, “Look, I’m going to put you in a whole lot of special effects makeup, it’s gonna take about five and a half hours to get into, it’ll probably take two hours to get out of. You’ll be there long before any of us, and you’ll be there long after us. However, I promise you, I will never use you for nothing. I will get you ready and shoot shoot shoot shoot shoot.” And he was as good as his word.

But when we were rehearsing There’s not much time to rehearse when you’ve got tens of millions of dollars at stake and hundreds of people standing around looking expectantly at you. You’ve got to do your homework! But because it was me and Tony, Ken could talk in a Shakespeare shorthand, He’d just say, “Tony, that’s King Lear; Colm, a bit of A Winter’s Tale, Act Two, Scene Two, you know what I’m talking about…” And that was fantastic. It saved us an enormous amount of time and kickstarted what we put on screen.

Also, I think the reason—well, I’m hoping the reason—that I was hired was that Ken had some faith in me… You know, I think when he’s hiring for big, classical, mythological-sized stories, like Thor is, he needs actors who grasp the size and scope of the thing. And he spent a year, I think, working on the script to make it more like Shakespeare, to give it a real classical foundation, so we were enormously recognizable mythological archetypes, whether we were Norse gods or King Lear or whoever. And in order to play that stuff, it doesn’t hurt if you have decades of classical theater training, because we instantly know, “Oh, it’s poetic, it’s pitched, but it’s not insincere. There’s nothing disingenuous about it. In fact, it’s hyper-real!” So I’m hoping that’s why I got the part. [Shrugs.] But doesn’t matter: I got to do it, I cashed the check, I came home, and it cleared. [Laughs.]

CF: So I got that role because they were looking through pictures, and there were pictures all laid out on the table, and I had at the time a rather gaunt and frightening-looking… I mean, look at this face. [Laughs.] It’s good for classical acting. You put on a mustache, you put a beard, you put a monocle, like in The Umbrella Academy. You know, I can change. But it’s mostly scary. It mostly looks like a death’s head in a ring, as someone said to me. And I asked David Twohy, “How did I end up here?” And allegedly… he said, “Well, I saw this picture, and I said, ‘That’s the face under the mask!’” I don’t know if you remember the film, but at some point he comes down, having conquered this world, and the magnetic piece just comes away, and essentially it’s the same features underneath. So it’s as good a way to get a job as any. And I wasn’t going to complain!

And we had an awful lot of fun doing it. We had a set built. What you see for our sort of throne room set was actually built two stories high, all filmable, playable, stand-on-able. The things you can do with styrofoam! And out there in Vancouver, we became one of the biggest draws on electricity… and I say this not with pride but with a certain amount of wonder. We were like a small city next to Vancouver. We were number two only to them, because we were drawing for all these lights, this huge warehouse full of studio equipment. But it was really a cool thing to shoot, because as you could see, it was going to have an enormous amount of post-production and CGI. But we could do an awful lot of that otherworld, off-world stuff right there, because they’d built those things! And that was enormously helpful, because I’ve got a fairly vivid imagination, but not that vivid!

So they were spending a lot of money, and we were hoping that once the studio saw how good we were, they’d give us a lot more money. Because some of the producers got fired for overspending early, so we had to batten down the hatches and be a little tighter. And then the studio didn’t trust David [Twohy]’s cut. They thought, “Well, it’s got to be quicker, it’s gotta be this, it’s gotta be that.” Turns out the director’s cut is the best version of the movie. When you take a lot of the other stuff out that they thought streamlined it, it didn’t make any sense. So his cut is the one you need to see, and it’s become a cult film. It’s fantastic! It keeps playing and playing, so I’m enormously proud of being a part of it. In fact, if somebody says, “I think I know you from something,” I use it as a gauge to figure out who I’m talking to. “Storm Of The Century? 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould? Chronicles Of Riddick?” But it was a really tough film to shoot, because it was so rigorous and all the gear and gak we had to get into.

And Judi Dench—they had wooed her, because Vin’s a very smart guy. He said to David, “Look, we’re going to announce this film…” The first one was Pitch Black, which they did for pennies in Australia and which was super cool. And then you had David and all these folks who came back and were also in Chronicles. So Vin knew that he needed a hook, and he knew he had this ethereal creature, and he knew he wanted someone completely unexpected. So he gets David Twohy on a plane, they fly to London, and they fill Judi Dench’s theater dressing room with flowers. And they go to her show, and then they knock on her door afterwards, saying, “Judi, you’re extraordinary. Hope you enjoyed the flowers! We need you to be in our movie.” And she’s like, “Oh, I don’t know if I can! I’m doing James Bond, I don’t know…” [Firmly.] “You need to be in our movie.” [More enthusiastically.] “It won’t take long! You can fly into Vancouver, it’ll be lovely, you can bring whoever you like.”

So she had a few conditions. “Well, will I be floating and airy and can you not see my feet? Because that would certainly be different from my M stuff for Bond! And could I sort of disappear, and be sort of unrecognizable?” [Laughs.] Sort of, “Can I be in the movie but not be in the movie?” But she agreed, and she was absolutely delightful and absolutely fantastic to work with. And people said, “Vin Diesel’s doing The Chronicles Of Riddick with Judi Dench—what?!” Judi Dench? Dame Judi Dench is doing an action movie, a sequel to Pitch Black, with Vin Diesel?” “Yes! It’ll be massive! And they’ve got Linus Roache, and a bunch of unknown people who come very inexpensively! The clothes are more costly than the actors!” But her presence had exactly the desired effect.

At one point, they kind of forgot that me and Vin have this enormous fight to death at the end. And then they thought, “We’ve got to shoot this after lunch!” And usually these things take months to rehearse! So I said, “Okay, you’ve got to do a huge swordfight or stickfight between me and Vin, and most of it’s got to be me.” Yes, there are some stunt doubles, but back in the day, the technical method of choice for doing that stuff was face replacement. So I’d do some of the stuff, and then they’d clone my face and put it on the stunt guy, who was better at this than me—and, y’know, expendable! And he’d come around and do half of it. But I had to do an enormous amount of it. And so I said, “Listen, I’m a classically trained actor—Hamlet, Romeo, Macbeth—so just give me the sword, give me the stick, give me a few moments with the stunt coordinators and guys, and I’ll be able to do this.” And they said, “Really? You can do that?” I said, “Have you not seen Hamlet? The fight’s after three and a half hours of talking, but trust me.” [Laughs.] So we did it, and we got on with it—and just by the skin of our teeth! I would’ve liked six weeks to rehearse it, but we got about 20 minutes. So you do what you can. But it held up, and it works.

What I was really hoping for, though, was that the film would be really successful, because one signs deals in perpetuity for those kinds of things, and I really fancied a second and third part of this. Because I’m sort of now dead, undead, totally dead, in some other world, and it’d be me and Judi Dench in white flowing robes, trying to help out Vin Diesel. “Vin! Vin! This way!” [Laughs.] And then for the third episode, he comes back: “Sorry! Sorry! This way!” And we’d guide him there, we’d cash our checks, and we’d go home!

CF: Again, it’s post-Glenn Gould stuff, so I get there and John Woo, an absolutely delightful man who subsequently hired me again in Paycheck, my third Ben Affleck movie, the one with Uma Thurman and Aaron Eckhart, where I play Wolfe, an executive assistant with guns. But in Face/Off, I’m the guy who takes their faces off. And as I said recently to the 20-year Canadian Medical Association meeting, which I was hosting, “You know, some of you may know me from an operation that is now commonplace, but I did the first one. The first face replacement, and, y’know, I reversed it two hours later! So not bragging, but… that happened. I was groundbreaking, obviously…”

But John was so delightful. I was offered the part, I think, because of my classical acting background, I was pretty good at the technical gobbledygook that needed to be done as you’re explaining to John [Travolta] and Nicolas [Cage] how their faces are going to be removed and put back, how their voices will change, etc., etc. And John [Woo] sort of thought that was fun. So I get the offer, I get down there, and on my first day, John comes up to me, he’s fit, he was smoking at the time, and he said—and he had an accent, so I’m not making this up—“So! Welcome! You meet John?” “Yes.” “You meet Nicolas?” “Yes.” “Okay! Uh… You make character. Have fun!” And he walks away! [Laughs.] But it was wonderful! I thought, “He trusts me! He trusts me to do this!” And I had such immense affection for him. And it is a marvelous film. It broke records. The action boat scene alone is extraordinary. The things John could manage to do when he was given tons of money, never mind his Hong Kong action films, which are extraordinary and which is presumably why Travolta said, “I want him! And you’ve got to let him do what he really does, but on a Hollywood scale!”

But at the end, it got rather bad, because… Tommy Flanagan, the brilliant Scots actor, was in it, playing one of the bad guys, and there was C.C.H. Pounder and I and another actor, we were all scheduled to die. And because the film had gone rather over… the bad guys are rounding us up, and one of us was supposed to go off a cliff, one of us was supposed to die in his lab. But at the end of it, they’d run out of money, and they’d run out of time, and John said, “Are these people available?” And there were three of us. He said, “Can you just get all together? We’ll tie them in a rope and light the room on fire!” Finally, they say, “Okay, we’re gonna kill all of your characters today. But we’re going to do it together. So the scene that you were going to do? You’re not doing. You’re doing it together. And we’re going to tie you to all these other actors.”

Now, one shoot or another had gone wrong over the course of filming, so I had at reservation at Wolfgang Puck’s Chinois, the one that did the lobster thing. It was brilliant. And I had a reservation with a friend and his partner, and we had been meant to go a year before, and the credit was expiring… and it was this night that we had the reservation. So we had to go! So if you look at one of the most dangerous scenes in Face/Off… You thought the guns and the explosions and everything else were dangerous? No, when they were lighting this on fire, this was many, many years ago, so they had some gas propane bars and then a lot of liquid glue that they just lit on fire! The whole room was up in flames with a bunch of special effects guys going, “Uh, I’m not sure… I don’t think that was supposed to happen!” And in the middle of it, we three actors are tied together, and the other actors are going, “Oh, my god! I don’t want to die this way!” I’m going, “Just burn me! I have a reservation at 7 p.m.! Just light the damned thing on fire and let’s get on with this!” And I wish I could tell you that that’s not what I was thinking, but it is. But it looks like gritty determination, a man accepting his fate. [Laughs.] But it was a riot to do!

Listen, I’ve been so lucky. Here in 2021, in the middle of this stupid pandemic, I am nothing but grateful for the hundreds of things I’ve managed to do in the theater, in the cinema, on the TV, everywhere else. And so I know I say like a broken record that these were delightful people and that they were always fun to do, but… I haven’t worked with any assholes. I just haven’t. Only delightful people. And when I list these directors I’ve worked with, like John and Sidney, Clint Eastwood and Michael Mann, Julie and Francois, all these people… I want to pinch myself, I feel so lucky and grateful.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.