Columbus is a lovely ode to architecture and the people who love it

It’s become a mortifying cliché to call the setting of a movie “one of the characters.” (That goes double if the setting is New York City.) So say this instead for Columbus: Its setting is every bit as important as its characters. True to its title, this gentle and often quite lovely American drama takes place entirely in the small Midwestern city of Columbus, Indiana, where it was shot. Columbus’ claim to fame is modernist architecture. You could guess as much watching the film on mute. Spired churches, oddly shaped conference centers, skyways stretching photogenically against actual skies: Buildings dominate this movie. Even when the people are the main focus of a shot, there’s usually some marvel of glass and steel looming behind them or poking into the frame. And even when the camera plops down indoors, it captures a kind of architecture: the library bookshelves shot to look like rows of apartment complexes, or the designer chairs that would fit snugly into a futuristic skyline.

No, Columbus isn’t a character in Columbus. But it is a topic of conversation for the characters. Jin (John Cho) has come all the way from Seoul to see his estranged father, a renowned architect who’s fallen suddenly into a coma. Budding “architecture nerd” Casey (Split’s Haley Lu Richardson) is a recent high school graduate who works at the local library, terrified to leave for college out of concern that her recovering meth-addict mother (Michelle Forbes) will relapse in her absence. Drawn to each other’s loneliness, the two strike up a dialogue over bummed cigarettes and end up spending a few days, on and off, wandering the city—Casey waxing poetic about her favorite buildings while they both talk about and around the parental issues keeping them planted in this mecca for modernism.

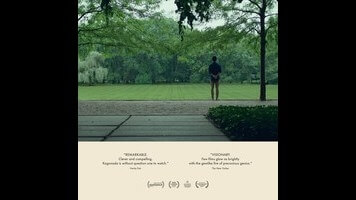

There’s a touch of Richard Linklater, he of the ambulatory two-handers, and also of Jem Cohen, whose Museum Hours asked similar questions about our relationship to art and history, in these digressive discussions. That makes sense, as Columbus is the first feature by Kogonada, a video essayist and film critic with a deep well of influences (including Linklater—he made a tribute to the director that ended up on the recent Criterion Before-trilogy boxset.) A lot of promising debuts wear their inspirations on their sleeve, but Kogonada has refined tastes. Adopting a style more reminiscent of contemporary Asian film than the average American indie, cinematographer Elisha Christian captures Columbus and its residents in static, carefully framed wide shots, sometimes shrinking the actors in proximity to striking structures, other times just leaving them out of the frame entirely. It makes for some of the most tranquilly gorgeous imagery of the year: a smitten sightseer’s view of the city.

As a film by a film critic, Columbus is sometimes self-aware to a fault. It often recognizes and acknowledges its own flaws; when Casey’s town trivia begins to resemble the rehearsed patter of a tour guide, Jin calls out the artificiality of the dialogue. There are moments when the people onscreen seem to be writing aloud the analysis of the movie they’re in: “Are we losing interest in everyday life?” asks Casey’s co-worker and potential beau, and only Rory Culkin’s pitch-perfect delivery of the speech keeps it from landing like a blatant mission statement. Still, there’s an unmistakable personal dimension to the endless chatter about what moves these characters and why. Like Jin, Kogonada was born in Seoul and later found his way to the Midwest, but Casey is the clearer onscreen surrogate—someone constantly working to square her growing knowledge of architecture with her complicated personal feelings about it. Sort of like a critic, no?

Even when it does sound like something you’d read in a city guide, the shop talk is a welcome accent. It makes a slender, perhaps overly familiar story—a platonic romance between two people running in place—feel a little more distinctive. The casting helps a lot with that, too. Cho, in a too-rare leading role, delivers the kind of sensitive performance that’s always banged at the lid of his franchise work. (He never gets the credit he deserves for making Harold of Harold & Kumar a real person, no matter how wacky the hijinks erupting around him get.) And Richardson, graduating to a grown-up headlining role after a run of supporting turns as high school kids, puts an appealingly mellow spin on post-adolescent anxiety, that paralysis before the scary headlong leap into adulthood. The two have a laid-back chemistry, an easy melancholy communion, that stops Columbus from ever feeling too academic. Come for the breathtaking architectural scenery, stay for the likable pair staring up at it.