Rave and Time Zone J illuminate the past with unique artistic visions

Jessica Campbell and Julie Doucet's new comic-book works explore the impulses and anxieties of youth

At its best, the comic book medium is a conduit for pure, unfiltered perspective. In the hands of a single artist, the fusion of words and pictures on the page provides an opportunity to show how one person interprets the world. That’s not to disparage creative teams where writing and art are handled by different people, but there’s a special kind of magic in works by solo cartoonists.

That magic is on full display in two new books from Drawn & Quarterly. Jessica Campbell’s Rave is an “auto-bi-fictional-ography” (a term coined by cartoonist Lynda Barry) pulling from her own past experiences to craft a fictional story about a teenage girl discovering her sexuality in a conservative religious environment. And Julie Doucet’s graphic memoir, Time Zone J, also takes a journey to the past, recounting a turbulent international love affair she had in her early 20s. It’s Doucet’s first new comics work in 15 years, taking her back to the start of her comics career to explore the heightened emotions and new discoveries of young adulthood.

Visually, the two books are completely different. Rave is built on comic-book fundamentals—square panels on a set grid, cartoony figures that make it easier for the reader to project themselves onto the story—whereas Time Zone J abandons panel borders and any conventional presentation of setting and character, unfolding as one long continuous image that embeds the narrative in a sea of other drawings. The printing for Time Zone J is particularly distinctive because the pages are folded over and uncut, allowing the art to flow seamlessly across the page turn. The stream of consciousness is never interrupted, and it’s a prime example of how Drawn & Quarterly’s impeccable production design supports the artist’s vision.

Julie Doucet became an alt-comics icon with her Dirty Plotte series in the ’90s, exploring the struggles in her career and personal life with unflinching honesty and an endearing sense of humor. Exhausted by the grueling hours of making comics and the stress of working in a male-dominated industry with few female colleagues and little encouragement to experiment creatively, Doucet left comics in the ’00s to pursue other artistic endeavors, like poetry, collage, sculpture, and even a short animated film, My New New York Diary, with director Michel Gondry in 2010. This year, Doucet was awarded the Grand Prix at the Angoulême International Comics Festival, the highest award in European cartooning.

The title of Time Zone J stems from the letter designations time zones (of which J is the only letter not used). Consequently, reading Time Zone J feels like traveling to a place that exists on no map, pulling you into the chaotic landscape of Doucet’s mind. It’s an initially intimidating read, demanding that readers rewire their brains to process the rush of visual stimuli and Doucet’s rapidly shifting thoughts. The book was drawn from bottom to top and should be read accordingly, but even then, it’s not always clear which way the eye should move. That’s a feature, not a bug, and there’s a level of trust involved here that makes for an especially rewarding experience if you embrace the spontaneity of her work, which is driven by the mercurial sensations of memory.

Time Zone J begins with Doucet grappling with her return to the comics medium and drawing herself again, creating tension between the past and the present. The need to tell this story was strong enough to pull her back to the art form she had left behind, and before she can delve into her doomed romance with a French soldier, she has to sift through the baggage she’s gathered since then. Once Doucet reaches the romance, she’s provided enough context for readers to place themselves in her shoes and get swept up in the throes of a dangerous and unsustainable passion. Rather than explicitly drawing those heated moments, the artist draws herself telling the story, inviting readers to shape those events in their minds.

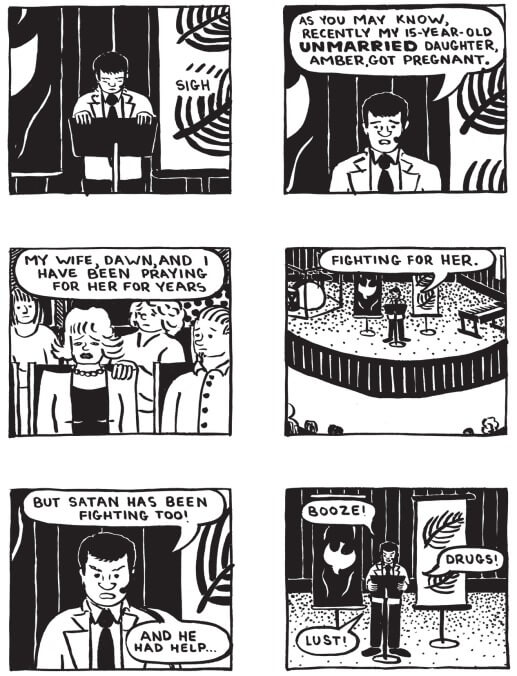

While Doucet challenges traditional comics structure, Campbell highlights why the formal conventions of comics are so effective at conveying expression while inviting personal interpretation. It’s been a pleasure to see Jessica Campbell develop her cartoonist voice over the last six years. Her works for Koyama Press, Hot Or Not: 20th-Century Male Artists and XTC69, spotlighted her talent for satire as she skewered the fine art world in the former and contemporary misogyny in the latter. Rave is a big shift from these previous works, an intimate coming-of-age tale that is especially timely in a climate where conservative groups are once again cracking down on sexual education and expression.

Campbell uses a set six-panel grid to invite readers into Lauren’s world, and then changes that rhythm to reinforce specific moments, whether it’s turning six panels into 12 to slow down the passage of time during a moment of acute embarrassment, or throwing in a two-page spread to emphasize the authority of the church. She repeats certain layouts to contrast emotional circumstances, and the six panels of Lauren talking to her crush on the phone have a completely different energy than the six panels of Lauren waiting for her crush to call.

A subliminal visual element in the six-panel grid speaks to Rave’s themes. The panel gutters make a crucifix shape (both right side up and upside down), and while this may not be intentional, it’s impossible to un-see. The influence of the church is always there, but so is that of the occult, offering a belief system that doesn’t restrict and condemn her desires. Lauren is drawn to that alternative lifestyle when she’s paired up with a queer, Wicca-practicing classmate for an assignment about evolution, but the fear-mongering and sexual shaming of Lauren’s religious upbringing is ultimately an obstacle too big to overcome at such a vulnerable age.

Rave and Time Zone J explore the impulses and anxieties of youth from distinct angles that showcase the versatility of the comic-book medium. Campbell uses the freedom of fiction to expand beyond her personal lived experience, delivering a more generalized story about the pressures of adolescence that takes advantage of the standard set of comics tools to be more accessible. That’s not a concern for Doucet, whose work feels like it’s been done solely for herself, using art to process a relationship that’s lingered in her mind for decades.