Complete Unknown is beguilingly mysterious, until it isn’t

The first six minutes of Complete Unknown constitute the most arresting, confounding opening sequence in recent memory. One of the film’s stars, Rachel Weisz, is first seen looking at a room for rent; she tells the landlord that her name is Connie, that she’s just back from touring the Amazon rainforest with a group of botanists, and that she’s planning to study environmental law. No sooner does she say this, however, than the movie abruptly cuts to Weisz in a surgeon’s smock, attempting to calm a badly wounded patient on an operating table. The doctor’s name is Paige. Seconds later, Weisz is Mae, a magician’s assistant in what appears to be China. Then she’s in business dress, surveilling a house in Ohio. Then she’s in bed next to a man with an Australian accent, talking about her years as a teacher back in the U.S. Finally, just before the title appears, we see her swimming out to sea, despite “Connie” having told the landlord a few minutes earlier that she didn’t get into a boat in the Amazon because she can’t swim.

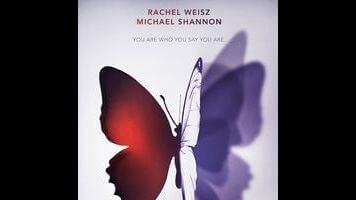

These could easily be scenes from five or six completely different movies starring Rachel Weisz, especially since she looks strikingly different (hair, makeup, clothes) in each one. But Alice—the name Weisz’s character uses for the bulk of Complete Unknown—isn’t an actress, and these seemingly random interludes genuinely represent her bizarre life. That history gradually comes into focus when she attends a dinner party with a guy she’s just started dating and immediately starts getting funny looks and fielding semi-hostile questions from Tom (Michael Shannon), whose birthday everyone is celebrating. Tom eventually corners Alice and confirms that she’s who he thinks she is, though he can hardly believe it. Revealing anything more than that would require stripping the film of one of its key pleasures, which is simply provoking the question “What the hell is going on here?” Let’s just say that Alice revels in the liberation of not being tied to anything—not even a personal identity. She’s “like a rolling stone,” one might say.

It’s an intriguing premise, and while writer-director Joshua Marston (Maria Full Of Grace, The Forgiveness Of Blood) never quite figures out where to take it, he sustains the sense of mystery for as long as he possibly can. The birthday-party sequence, which takes up roughly the first third of the movie, is a formal tour de force; Marston uses glancing, nervous camerawork to foreground Alice’s restlessness and Tom’s anxiety, all the while juggling half a dozen other guests with consummate ease. Later, Alice and Tom encounter a couple played by Kathy Bates and Danny Glover, and when Alice improvises an utterly phony backstory for Tom, without warning, he finds that he rather enjoys playing along with the fiction. Even toward the end, as suggestion gradually and inevitably gives way to exposition, there are still captivating pleasures to be found, including an interlude in which Alice takes Tom on a tour of a frog-filled swamp. It’s the sort of tantalizing enigma that one desperately hopes will end powerfully, rather than just sort of fizzling out.

Unfortunately, Complete Unknown completely fizzles. Apart from the moonlit frog bit, Marston and his co-writer, Julian Sheppard, can’t think of much for Alice and Tom to do once they’re alone together; the last act of the movie consists largely of Alice explaining her philosophy of life in tedious detail and Tom insisting—with logic that’s hard to fault, frankly—that said philosophy is selfish and deranged. It’s a drastic turnaround from the disorientation that reigns early on, and while that’s thematically apropos for a story about reinventing oneself at will, without looking back, the shift from abstract to concrete just doesn’t satisfy. It’s as if a first-rate Roman Polanski movie suddenly metamorphosed (ohhh, frogs, duh) into a third-rate Michael Crichton adaptation. The visually magnificent final shot only compounds the frustration, as it’s in service of a real shoulder shrug of an ending. Marston, whose previous two features looked like fairly standard no-budget indie fare, has made a huge leap forward here as a director. Next time, hopefully, his script will provide the images with a more esoteric, less pedantic context.