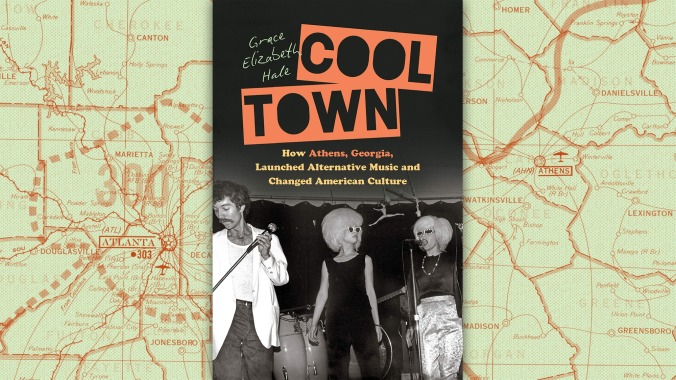

The modern alternative music scene began, most appropriately, at a house party on Valentine’s Day, 1977. The performance was simultaneously an embrace and a kiss-off of just about everything new, old, and in between that contemporary pop music had to offer: punk, new wave, disco, dance, surf, and funk. In their first-ever public gig, three gay men and a pair of beehived women, all dressed as if a thrift store had exploded on stage, sang songs about marine animal beach parties and a pink-aired planet named Claire. Starved for something, anything, new, the crowd had so much fun that they watched the band perform the six-song set of weirdo originals a second time through. At The B-52s’ second concert, another house party a week later, a friend of the band could be heard, over the dance-mad din, screaming again and again, “I can’t believe this is happening in Athens, Georgia.”

Athens was nothing if not happening in the dozen-plus years following that first mythic show. And in Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music And Changed American Culture, historian Grace Elizabeth Hale makes the case that without the small Southern college town, there would be no grungy Seattle, no hipster Williamsburg, no weird Austin.

Like those boho hotspots, Athens was overwhelmingly white. Unlike those places, Hale argues, Athens’ scene incorporated many female and queer artists, none more soon-to-be-famous than Michael Stipe, lead singer of R.E.M., arguably the most influential post-’70s rock band (just ask Kurt Cobain, Thom Yorke, or Patton Oswalt). Hale enrolled at the University Of Georgia in Athens just as R.E.M.’s debut EP, Chronic Town, hit record bins and college radio stations, and she does a good job of reconstructing the band’s fabled early years, from their first performance in a ramshackle former church to the love-hate relationship with the town they called home—even as endless tours beckoned. In 1983, Rolling Stone named R.E.M. “the important Athens band.” Local scenesters denounced them as conservative and the “‘digestible-by-frat-boys’ version of the Athens sound.” The band’s guitarist, Peter Buck, bit back. “I think the whole Athens thing is blown up,” he said in an early interview. “It’s just a dumpy little town.”

Hale does an even better job resuscitating those bands that did not play Japan numerous times, those artists the frat boys hated. People like Jeremy Ayers, Athens royalty who escaped to New York and joined up with Warhol’s Factory, where he took the name Silva Thinn. He returned home to become a townie Svengali who wrote songs for the B-52s and R.E.M. and mentored many gay young men-turned-artists (he even briefly dated Stipe who, Hale claims, copied Ayers’ angular, akimbo, scarecrow dance style.)

The Athens sound of the ’80s had no unifying aesthetic, Hale writes, beyond a creative, DIYer amateurism. Many of those bands were able to score national album reviews and patch together tours simply by billing themselves as hailing from what one music journalist called, “the most famous city of its size in the world.” Hale documents groups long lost (like the Bar-B-Q Killers and her own band, Cordy Lon, in which she played the cello before heading off to grad school), those you might remember (Love Tractor), and at least one with serious indie cult cred (Pylon, Pylon, you should be listening to Pylon, who opened for the Talking Heads, U2, and, in 1987, was named the nation’s best band by R.E.M.’s Bill Berry).

Eventually, bands like Butthole Surfers and Flat Duo Jets relocated to Athens for brief stays to capitalize on the town’s renown. A second wave, most notably Vic Chesnutt, the Drive-By Truckers, and the Elephant 6 collective (including Neutral Milk Hotel, Of Montreal, and others), found greater success. It’s likely that your favorite hometown band also attempted to make a go of it in Athens—shout out to Lafayette, Louisiana’s UrboSleeks—and Cool Town should inspire widespread ransacking of old shoeboxes to dig up forgotten cassette tapes.

Many of those bands, big and small, have packed up their gear and relocated elsewhere. The B-52s still tour, but R.E.M. stopped performing together nearly a decade ago. Today Athens looks more and more like any other university town: gentrified, hellscaped with student condos, frat- and football-obsessed, but also friendlier to outcasts of all stripes, a glorious city, an alternative forebear in a world where most every municipality can claim an alternative scene. “Don’t feel out of place,” The B-52s sang on their debut album “’cause there are thousands of others like you / Others like you / Others like you.” Thanks to Athens, there are others like us.