Cosmos is a fittingly strange swan song for the late Andrzej Żuławski

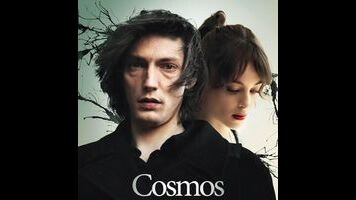

The late, one-of-a-kind Polish writer-director Andrzej Żuławski liked to set movies around vortices, at least figuratively. His final film, the Witold Gombrowicz adaptation Cosmos, offers three of these: the dinner table of a French bed and breakfast, a stormy seaside, and a misty forest, each like the accretion disk of a black hole. In this droll, free-associative send-up of vacationing detective stories, a law student with the looks of a Byronic vampire becomes obsessed with a dead bird he finds hung from a string in the woods, its enigmatic significance just one sign of the invisible and unexplained force that warps the movie, freezing characters in tableaux vivant or leading them to scurry around the floor like the cast of an overheated stage farce.

Accompanied by his buddy Fuchs (Johan Libéreau), who often shows up with unexplained bruises all over his face, the pale-skinned Witold (Jonathan Genet) searches for truth in dinnerware and literary allusions, sometimes erupting into uncontrollable fits of convulsing, retching, and Donald Duck voice. In a movie where one character is inexplicably dressed like Tintin and another talks in a Professor Irwin Corey-esque mix of pseudo-Latin and baby talk, Witold counts as a viewer surrogate. He’s looking for meaning, which puts him in the same position as an audience confronted with close-ups of spoons being fondled or with an actress playing two different characters.

From the hold-music smooth-jazz score to the overtly theatrical performances, everything about Cosmos is designed to confound. It’s an adaptation of a Polish novel, filmed in Portugal, where the dialogue can shift from playful parody to grandiloquent allusion in a breath, and the camera is often slowly dollying back, as though it were about to reveal something just out of frame. The mutant aesthetic of Alain Resnais’ later movies (namely Wild Grass and You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet) comes to mind, perhaps because Resnais’ wife and muse, Sabine Azéma, plays the batty owner of the B and B. Even Cosmos’ visual style (short lenses, low angles, tracking shots) becomes distorted as it wears on, until Żuławski starts bringing in moviemaking artifice as yet another layer of unreality.

Made 15 years after Żuławski’s last film, Cosmos makes for a fittingly offbeat and mystifying statement of purpose for a filmmaker fascinated by confrontations with the cosmic unknown. (He could have made one heck of a Lovecraft adaptation.) It might seem weird for weird’s sake, and in some ways, it is; at any moment, the characters might drop to all fours to pick up peas or go off about Stendhal. Cosmos isn’t asking its audience to solve a riddle, but to accept the unexplained as the state of the universe, in which every random object or gesture seems to carries an aura of meaning yet resists interpretation. Hence the title.