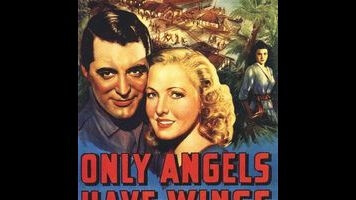

Cinephiles frequently cite 1939 as Hollywood’s greatest year, rattling off an impressive list of widely beloved classics: Gone With The Wind, The Wizard Of Oz, Wuthering Heights, Stagecoach, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, and so forth. Rarely mentioned, however, is Howard Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings, a stealth contender for the single greatest Hollywood movie of all time. That this glorious amalgam of romance, adventure, melodrama, and musical doesn’t have a loftier reputation is to some degree understandable—even more than most of Hawks’ films, it’s an ode to pragmatism and professionalism, dismissing almost any powerful display of emotion as a distraction from the task at hand and/or an admission of weakness. That sensibility only appeals to a very particular mindset… but for those viewers, Only Angels Have Wings achieves a seismic force that conventionally open-hearted movies can’t hope to match. With any luck, its forthcoming release as part of the Criterion collection will yield new converts.

The film’s first half-hour alone constitutes a dazzling tour de force of shifting dynamics. Initially, it appears to be an “exotic” variation on the fast-talking romcom, as showgirl Bonnie Lee (Jean Arthur) disembarks a ship in the (fictional) South American port of Barranca and immediately has a couple of mail pilots (Allyn Joslyn and Noah Beery Jr.) competing for her affections. When their boss, Geoff Carter (Cary Grant), insists that work come before pleasure, one of them winds up crashing his plane in his eagerness to keep his date with Bonnie, who’s subsequently appalled when Geoff and the other men show no outward signs of grief at their friend’s death. The movie turns heavy, only to soon lighten up again, as Bonnie talks to some of the locals and begins to understand what purpose this stoic behavior serves. Before long, she’s performing a jaunty number on the saloon’s piano, and in no particular hurry to get back on her ship, even though Geoff’s best friend, Kid (Thomas Mitchell), warns her that she’s setting herself up for heartbreak.

That’s more than enough for a whole feature, but it barely even scratches the surface of what happens in Only Angels Have Wings. While Bonnie seems like the protagonist for a while, she’s really just our point of entry into the film’s offbeat community; the primary set—a combination saloon-restaurant-office run by Sig Ruman’s blustery Dutchy—serves as a stage upon which multiple dramas and crises play out. The burgeoning love affair between Bonnie and Geoff gets puts aside for long stretches so that Hawks can turn his attention to Kid’s failing eyesight (which threatens to ground him—something he perceives as akin to death), or to the tiny airline’s newest pilot, Bat MacPherson (Richard Barthelmess), who has an ignominious history that puts him in conflict with Kid and a wife (Rita Hayworth, pre-stardom) who once dated Geoff. Hawks flits effortlessly back and forth among all of these strands, equally interested in everyone. One of the movie’s best jokes sees Geoff abruptly stop in the middle of a conversation, walk across the room, and throw open a door, causing an eavesdropping Bonnie to fall inside—it’s a slapstick moment, but it’s also a puckish reminder that wheels are turning outside of the frame at every moment.

The film offers genuine intrigue and excitement—including the pilots’ climactic, death-defying effort to save the airline by demonstrating that they can reliably deliver the mail even in treacherous weather. But its ultimate power derives largely from its unusual ethos, which celebrates pragmatism at the expense of emotional behavior while simultaneously acknowledging just how profound a pragmatist’s emotions can be. In particular, the resolution of Bonnie and Geoff’s relationship (which is also the final scene of the movie) eschews romance in a way that, paradoxically, makes the gesture in question achingly romantic. That’s par for the course in a film that’s built on internal contradictions, repeatedly engineering massive upheavals and then watching the characters blithely pretend that nothing of note has occurred, even as they die inside. One could carp that this represents a warped, toxic notion of masculinity (not an uncommon criticism of Hawks), but that would require ignoring the tenderness in Kid’s voice when he talks to Bonnie about Geoff, or Geoff’s willingness to give Bonnie what she needs from him even as he makes it appear that he’s withholding it (in order to protect himself from a potentially disastrous surge of unaccustomed vulnerability).

Thankfully, people are starting to come around. When Sight & Sound held its most recent poll in 2012, 11 critics (including this one) named Only Angels Have Wings one of the 10 greatest films of all time; only The Wizard Of Oz and Renoir’s The Rules Of The Game placed higher among titles from 1939. And that was before Hawks’ masterpiece got the Criterion stamp of approval, and the attention that inevitably follows. Check back again in 2022, and don’t be surprised if it’s inched its way even past Dorothy and Toto.