Criterion offers a loose trilogy from Wim Wenders, king of the road movie

A few years ago, Rian Johnson, who’s currently shooting the next Star Wars installment, joked on Twitter that “Looper will complete what I’m calling my ‘I made three movies’ trilogy.” It was a lightly sarcastic jab at the increasingly fashionable practice, indulged in both by critics and filmmakers themselves, of grouping three unrelated films by the same director, based on thematic similarities, and proclaiming them a de facto triptych. (The latest variation on this is the “spiritual sequel”: Everybody Wants Some, 10 Cloverfield Lane.) There are cases where that feels legitimate, though, and Wim Wenders’ “road trilogy,” which Criterion is releasing as a box set next week, certainly qualifies. The three films in question were shot over three consecutive years (released in 1974, 1975, and 1976), and they all star Wenders’ favorite actor, Rüdiger Vogler, as an itinerant lost soul, traveling across Germany (plus America, in one instance) in search of something that’s never quite defined. As a crash course in New German Cinema, this is tough to beat.

Of the three, the purest road movie is the first, Alice In The Cities, which introduces Vogler’s recurring character, Philip Winter. (He doesn’t always appear to be the same person, but Vogler turns up with that name—later spelled “Phillip”—in four of Wenders’ films.) Shot in gorgeous black-and-white 16mm, the film begins with Winter driving across the U.S., ostensibly as research for an article about the American landscape, then shifts to Germany, where he’s saddled with a 9-year-old girl, Alice (Yella Rottländer), whose mother (Lisa Kreuzer) unexpectedly ditches her. Attempting to find the house where Alice’s grandmother lives, based solely on a photograph of its exterior, the pair wanders all over the country’s Ruhr area, and Wenders frequently subordinates their prickly relationship—Rottländer exhibits none of the usual child-actor affectations, coming across as a genuine little kid—to atmospheric detail. The most dramatic scene, set in a diner, gets evenly split between dialogue and a jukebox playing Canned Heat’s “On The Road Again,” beside which a little boy sits as if he were freezing and the music were a warm fire.

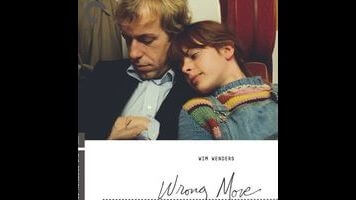

At the time, it’s unlikely that anyone saw Wenders’ next film, Wrong Move, as any sort of sequel to Alice, spiritual or otherwise. For one thing, it’s shot in color, giving it much more of a grounded, grubby vibe. For another, it’s a loose adaptation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, a bildungsroman that’s much more concerned with its protagonist’s psychological makeup than his travels. At 32, Vogler was a bit long in the tooth for the role of Meister, a young man leaving home for the first time, but Wenders mostly uses Goethe’s tale as a clothesline upon which to hang a series of increasingly moody and volatile encounters, involving Therese (Rainer Werner Fassbinder regular Hanna Schygulla), an actress with whom Meister becomes smitten after catching sight of her on a train, and Mignon (13-year-old Nastassja Kinski in her film debut), a mute acrobat keeping disturbing company with a middle-aged former Nazi (Hans Christian Blech). The film leans a bit hard on voiceover narration and is far uglier and more depressive than the trilogy’s bookends but perhaps serves as a necessary corrective to the other two films, suggesting as it does that there’s no escaping one’s own inner nature.

Returning to shimmering black and white (in 35mm this time), Wenders then went for broke with the epic, three-hour Kings Of The Road, which won the FIPRESCI prize at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival (but lost the Palme D’Or to Taxi Driver). Vogler’s character is here called Bruno Winter rather than Phil(l)ip—the slight chilliness and Shakespearean discontent signified by his surname remains a constant—and his job is to make the circuit of small-town German movie theaters, checking on and repairing the projection equipment. By chance, Bruno witnesses a despondent man named Robert (Hanns Zischler) drive his car into a lake; Robert then joins Bruno for a while on his route, helping him lug heavy equipment and so forth. Most of the film was reportedly improvised by the two actors, and that approach’s strengths and weaknesses both get amplified by the lengthy running time. Highlights include Bruno’s dalliance with a woman (Kreuzer again) who runs the ticket booth at one theater, as well as a repair job at a school that somehow turns into a slapstick shadow performance when a light mistakenly gets switched on. But Kings Of The Road loses its way when it delves into its characters’ personal histories, getting especially bogged down during an interlude in which Robert confronts his estranged father (Rudolf Schündler) about the way Dad treated Robert’s now-deceased mother. True to its name, the road trilogy is at its best when it foregrounds geography, functioning as a dreamy travelogue. When Philip Winter runs through an alphabetical list of almost every city in Germany, trying to jog Alice’s memory, you want to visit them all.