The ongoing cinematic collaboration between André Gregory and Wallace Shawn is too peculiar for anyone to have possibly predicted. Both men started out in the theater—Gregory as an experimental director, Shawn as a controversial playwright—and they’ve carried their deep love of live theater’s immediacy into their work together on-screen. Said work is infrequent, consisting of only three features in the past 34 years. Two of the three are essential, however, and now Criterion has collected all of them into a box set with the catchy title André Gregory & Wallace Shawn: 3 Films. As with the Godfather box set, consumers will have to decide whether they want to pay for a third movie they don’t necessarily feel the need to own. (Each film can also be purchased individually.) But it’s pleasing to see this unlikely duo receive premium-auteur treatment, especially given the cheerfully unfashionable nature of their oeuvre.

An improbable sensation (by arthouse standards, anyway) at the time of its release in 1981, My Dinner With André ranks among the most daring conceptual stunts in cinema history. With the exception of a brief prologue and epilogue, the entire movie consists of Gregory and Shawn, playing barely fictionalized versions of themselves, sitting at a table in a fancy Manhattan restaurant (Café Des Artistes, which closed in 2009) and talking. That’s it. Just a movie-length conversation, in which Shawn asks Gregory what he’s been up to since they last met five years or so earlier and then listens, dazed, to a series of amazing anecdotes, eventually responding with an equally impassioned paean to his own ordinary, uneventful life. Directed by the late Louis Malle, the film works better than anybody ever thinks it possibly could; as Gregory eloquently recounts his adventures in vivid detail, each viewer’s imagination takes over, and yet the actors’ faces remain a crucial component. This odd alchemy proves more compelling than the central dichotomy between Gregory’s globetrotting spiritual quest and Shawn’s homespun defensiveness, which can start to seem a bit facile and overdetermined on repeat viewing (though it’s rooted in their real lives).

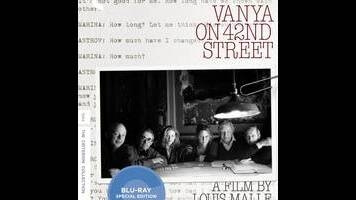

Thankfully, Gregory and Shawn didn’t perceive My Dinner With André’s success as a license to make a whole series of talkathons set in restaurants. (Take note, Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon.) Instead, they joined forces again 13 years later for Vanya On 42nd Street, a filmed version of a Chekhov production that they’d been workshopping on and off for several years, with Gregory as director and Shawn playing the title role. Shot in the then-vacant New Amsterdam theater, this Uncle Vanya, with English-language dialogue written by David Mamet, is acted in street clothes, with so little evident theatricality that those who don’t know the play well may not even recognize the moment when the cast stops horsing around and starts actually performing. Shawn makes for an overly peevish Vanya, but it hardly matters—the movie belongs entirely to the young Julianne Moore, whose interpretation of Yelena is dizzyingly counterintuitive; she somehow finds a deeper truth in every line by playing radically against whatever emotion the words seem to suggest. Malle directed this film as well—it would be his last, as he died the following year—and again succeeds in creating visual magic from a single-set, dialogue-driven picture. He must have felt truly liberated by the novelty of people who sometimes get up and move around.

With Malle gone, Gregory and Shawn turned to Jonathan Demme for their most recent collaboration, A Master Builder, based on the play by Henrik Ibsen. Reviewing the film upon its tiny theatrical release last year, I praised the performances—Shawn plays the elderly architect Halvard Solness, opposite Julie Hagerty as his wife and the little-known Lisa Joyce as a potential mistress—while complaining that Demme never manages to make this particular adaptation into something more dynamic than filmed theater. Also, Gregory’s choices, as the project’s original director, to change the entire story as Solness’ deathbed hallucination, don’t make a lot of sense in any medium. Still, Ibsen’s masterpieces rarely go before a movie camera, so those who get out to see live theater will find something of value here, even if this is unmistakably the least of Gregory and Shawn’s three collaborations to date. Since it also may be their last, given that both men are over 70, and that more than a decade elapsed between each previous film, Criterion’s box set serves as a fitting testament to a remarkable partnership.

All three films are available individually or as part of the André Gregory & Wallace Shawn: 3 Films box set from Criterion.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.