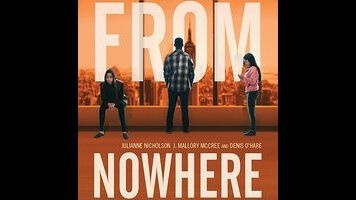

With so much media attention being paid to the court battles involving President Trump’s travel ban, his administration’s aggressive actions toward undocumented immigrants already in the country threaten to fly under the radar. It’s not that enforcement has been stepped up—Obama actually deported people in record numbers over the past eight years—but that the emphasis on potentially dangerous individuals has been considerably relaxed, leading to high-profile, heartbreaking cases like that of Guadalupe García De Rayos. No doubt we’ll soon see outraged documentaries on the subject. In the meantime, however, From Nowhere, a measured but fundamentally sorrowful drama about three undocumented teens applying for asylum, receives an ideally timed release this week, almost a year after its SXSW premiere. Back then, with Clinton an apparent shoo-in, the film was merely perceived as excellent. Today it also seems urgent.

While the three kids in question have all lived in the U.S. since early childhood, and barely remember the countries of origin to which they’re perpetually in danger of being shipped back, they come from wildly divergent backgrounds. Moussa (J. Mallory McCree, recently seen on Homeland) originally hails from Guinea, and has deliberately been told nothing about the nightmare from which his mother (Chinasa Ogbuagu) fled many years earlier. Sophie (fiery newcomer Octavia Chavez-Richmond) sometimes longs to return to the Dominican Republic, though that’s mostly because she’s being mistreated—and sexually assaulted—by the extended relatives who’ve reluctantly taken her in. We learn comparatively little about the third teen, Peruvian-born Alyssa (Raquel Castro), who’s relentlessly optimistic and is about to graduate as valedictorian of her class. Alyssa’s disposition is so sunny, in fact, and her prospects so bright, that any savvy viewer will eventually recognize that the character is being stealthily positioned as an upsetting worst-case scenario. She’s the equivalent of the war-movie grunt who makes the mistake of heaving a huge sigh of relief after surviving the initial onslaught. Wave bye-bye.

Even at its most mechanistic, though, From Nowhere largely avoids preachiness and sanctimony, preferring to wrestle with the real world in all its stubborn complexity. The film has two ostensible “white saviors”—a teacher (Julianne Nicholson) who’s trying to help all three kids and the immigration attorney (Denis O’Hare) to whom she refers them—but the former inadvertently causes as many problems as she solves, and the latter, while sympathetic, necessarily thinks in terms of what’s most likely to sway a judge, which means prodding Moussa, Sophie, and Alyssa to come up with traumatic personal histories that he can sell. Screenwriters Matthew Newton (who also directed) and Kate Ballen have no interest in creating cartoon villains, but they likewise refrain from creating plaster saints: Two cops who choose to ignore Moussa’s fake ID seem as motivated by their desire to avoid paperwork and get out of the cold as by kindness or empathy, and a landlord who refuses to take a family’s last penny, because he can’t bear to think of them going hungry, nonetheless still threatens to evict them soon if their back rent isn’t fully paid.

Most crucially, From Nowhere builds a wholly credible world around its issue of choice. Apart from the strategically marginalized Alyssa, every character is a person first and a pawn second—Sophie, in particular, has emotional problems that are distinct from (but exacerbated by) her legal predicament. Classroom scenes are utterly credible in their precarious mix of order and chaos; petty rivalries among the students would fit snugly into any other high school movie. (“Was I talking to you?” a girl belligerently demands of Sophie. “No, good choice” is Sophie’s smartass reply.) For a while, the movie even trusts the viewer to notice that Moussa speaks with an American accent at school but has a slight Guinea accent when at home with his mother and sister. Eventually, the sister brings this discrepancy up in dialogue, and there are a few other clunky moments that needlessly underline what’s already apparent to anyone paying attention. On the whole, though, this is a smart, sensitive, and subtle portrait of needless suffering among people who’ve built solid, respectable lives in the U.S., even if they (or just their parents) broke the law getting here. That it reflects what’s happening in the real world right now only makes it more distressing.