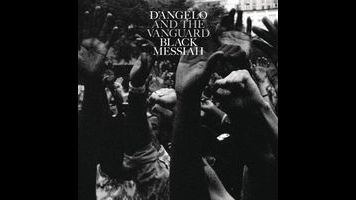

D’Angelo’s long-awaited Black Messiah is devastatingly great

What’s remarkable about Black Messiah, other than the fact that it actually exists, is how fresh D’Angelo sounds when slotted next to modern R&B artists. It’s the same trick The Roots pull off with every new album—sounding inherently classic yet completely of the present. There’s a thematic and sonic awareness to Black Messiah—credited to D’Angelo And The Vanguard—that makes it so much more than a long-delayed comeback album from an artist widely declared a genius some 15 years ago. It’s somehow the past, present, and future all in one.

The album most obviously akin to Black Messiah on a musical level is Sly And The Family Stone’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On; both are narcotic, weary, funky, and seductive. But there are also shades of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and Sign O’ The Times-era Prince, not to mention a heavy dose of Funkadelic and Stevie Wonder. The plethora of influences, instruments, and effects are revelatory; every arrangement feels like a living, breathing organism that can mutate and grow. On the politically charged “1000 Deaths,” it comes in the form of a shift from a blend of chunky, atmospheric riffs to a full-on, Eddie Hazel-inspired guitar freakout. It’s also present on “Sugah Daddy,” where a looping piano line and off-kilter handclaps occasionally recede into the background, making way for D’Angelo’s layered harmonies and panning studio effects.

For a record that obviously took a long time to produce, Black Messiah is surprisingly loose. Classical guitars weave around a wandering bass on the ballad “Really Love,” the inclusion of horns and strings never making the song feel crowded. The beauty of this record is in the balance: between the political and the personal, certainly, but also between tightly constructed harmonies and melodies, and the more free-flowing sense of rhythm. For instance, “The Charade” features one of the more ethereal arrangements on the record, with D’Angelo’s voice tweaked and layered to a surprising degree. It’s confounding, but then the lyrics poke through and suddenly there’s an urgency to the track, something to anchor it: “All we wanted was a chance to talk / ’stead we only got outlined in chalk / Feet have bled a million miles we’ve walked / Revealing at the end of the day, the charade.” Then there’s “Back To The Future (Part I),” a slinky funk jam that finds D’Angelo longing for the way things were. The singer is obtuse though, never really identifying what he wishes hadn’t changed. Himself? R&B? A romantic relationship? Black Messiah benefits from being so cryptic, managing to sound poignant, relaxed, and seductive at the same time.

Don’t mistake relaxed for complacent, though. Black Messiah doesn’t sound like anything else this year, or maybe even the last decade. It’s an album that pays homage to the history of black music, from blues, funk, and soul through to hip-hop and modern R&B while remaining in touch with current socio-economic and political struggles. Maybe that’s because those modern struggles aren’t so different from the ones in the past. Black Messiah confirms that music holds the power to challenge and comfort, to take us someplace spiritual, political, and existential. It’s beautifully, devastatingly human.