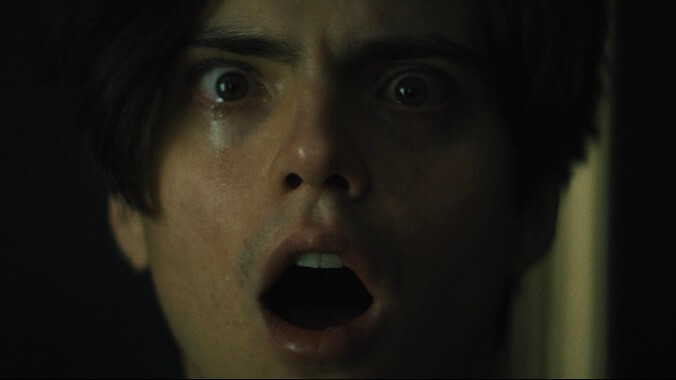

Photo: Samuel Goldwyn Films

Daniel Isn’t Real, a new horror movie from director Adam Egypt Mortimer, explicates its title almost immediately. From a foreboding opening image of a cosmic vortex, the film cuts to a brutal mass shooting, the aftermath of which 6-year-old Luke (Griffin Robert Faulkner) wanders upon while his parents are fighting in their New York apartment. When his frazzled mother, Claire (Mary Stuart Masterson), eventually finds him in a nearby playground, he asks if his friend Daniel (Nathan Chandler Reid) can come for dinner. Although she sees no one else, she plays along, too preoccupied with her impending divorce to deal with a harmless imaginary friend. But things soon go horribly wrong when Luke, at Daniel’s behest, laces his mom’s drink with a bottle of pills. (“They’ll give your mom superpowers,” Daniel says.) As a consequence, she orders Luke to lock Daniel in his grandmother’s antique dollhouse (an amusing bit of Jungian symbolism). Flash-forward a decade, and Luke (Miles Robbins) is now an awkward, mopey college freshman. It’s not so much a matter of if the dollhouse will be unlocked, but when.

Adapted from the novel In This Way I Was Saved by Brian DeLeeuw (who also co-wrote the script), Daniel Isn’t Real soon brings to mind David Fincher’s cult classic Fight Club. While attempting to help his mentally ill mother—he later checks her into a psychiatric ward—Luke decides to free Daniel (now played by Patrick Schwarzenegger), who becomes a kind of Tyler Durden figure. Eminently attractive, creative, and charismatic, he coaches Luke through various social interactions. Though previously sullen and reclusive, Luke starts hanging out with an aspiring artist named Cassie (American Honey’s Sasha Lane), though because of Daniel’s meddling, he also gets involved with Sophie (Hannah Marks), a psychology major he meets at a house party. (In one of the film’s more bizarre, blatantly homoerotic touches, Daniel takes his shirt off to help Luke during an exam, revealing a set of formulas and answers written on his torso.) Inevitably, as Daniel becomes increasingly malevolent, things spiral violently out of control, and Luke becomes desperate, wondering whether he might have inherited his mother’s schizophrenia, or whether Daniel’s presence is something else entirely.

It’s to Mortimer’s credit that none of this really feels like it was adapted from a novel. The director makes no attempt to replicate the subjective ambiguity of DeLeeuw’s novel in the way that Fincher did for Chuck Palahniuk’s; he opts instead for effects-heavy set pieces (including two gnarly body-horror scenes), as are only appropriate for a film from the producers of Mandy. But the story’s general trajectory isn’t exactly novel, and plays like a mélange of familiar tropes: Viewers need only look to Ari Aster’s Hereditary for a thematically similar blend of psychological horror and supernatural fascination. And even more than that, Mortimer’s film ultimately lacks a behavioral or emotional acuity to match its over-the-top imagery. Beyond the central Luke/Daniel dynamic, there’s no appreciable interest in Luke’s social or domestic life beyond what’s required to set the story in motion, which makes the film’s violent turns (not to mention its ostensible preoccupation with childhood/family trauma and mental illness) ring especially hollow. Mortimer builds Daniel Isn’t Real to a conclusion that, in concept, should be both tragic and terrifying. Here, it just feels perfunctory.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.