Danny Fields was the Forrest Gump of proto-punk

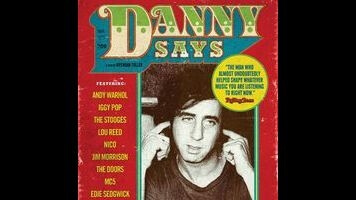

The music industry hasn’t traditionally earned much fame for its behind-the-scenes players—perhaps because the rock stars actually making the music are particularly difficult to outshine. Sure, the music biz has its share of names that don’t actually play instruments or produce records, but how many immediately spring to mind? Beatles manager Brian Epstein, maybe. Colonel Tom Parker. Interscope impresario Jimmy Iovine. But even those titans of the industry aren’t household names, or even close. Danny Fields, the subject of Danny Says—and of the Ramones song that gives the documentary its name—is several steps below those players on the fame ladder, though Brendan Toller’s film posits that he’s no less vital to the history of popular music.

To hear Fields tell it—and a lot of Danny Says features the man himself telling his own stories—he had great taste in forward-thinking music, and he was in the right place at the right time, many times. Like the Forrest Gump of proto-punk, he partied with Andy Warhol at The Factory, lived with Edie Sedgwick, befriended Lou Reed and Linda Eastman (who’d later be Linda McCartney), and introduced Nico to Jim Morrison. That’s not all. He got both The Stooges and MC5 record deals with a single phone call to Elektra Records shortly after seeing them play for the first time. He introduced Iggy Pop both to cocaine and to David Bowie. And in one of the last huge moments of his career, he guided the Ramones to their earliest fame, sending them to England where they hung out with Paul Simonon—whose band The Clash was afraid to play live because they weren’t technically skilled enough. (The Ramones taught them they didn’t need to be, apparently.)

The stories wouldn’t be half as fun if Fields weren’t so refreshingly cynical and candid. Unabashedly gay at a time when that was a considerably rarer thing to be, Fields spends nearly as much time talking—mostly in generalities—about freewheeling sex as he does about the music he was witnessing and helping to promote. He came to grips with his sexuality in college and dove right in, and he’s perfectly New York in describing those years, talking with a smirk about how he “hung out with dissolute faggots, shoplifted, and fucked a lot.” He’s also hilariously unafraid to call bullshit on things he didn’t connect to in his career: He can’t even remember which Winter brother he briefly helped out, so he dismissively says stuff like, “One of the albinos was playing.” In other words, he’s kind of an asshole—but the mostly likable kind.

Fields’ actual roles were widely varied: As an editor at a teen magazine, he brought the Beatles’ “bigger than Jesus” controversy to the public eye and helped end their touring career. Sometimes he was a journalist, sometimes a publicist, sometimes a manager. But in every role, his goal was to, in his words, “see a miracle and encourage it to be miraculous.” He had an incredible ear and eye for talent: He talks as much about artists’ looks as he does their music, though in a way that comes across more matter-of-fact than creepy.

A bunch of Fields’ war stories are rendered with simple animations, and while those aren’t as effective as the dozens of great photographs that dot the film, they do break up what might otherwise be an overly talky doc. His story about hiding Jim Morrison’s car keys—and, of course, seeing the Lizard King’s penis—are told and drawn crudely but effectively. He’s also got some audio of conversations with Iggy and Lou, including Reed’s first exposure to the Ramones. (He’s shockingly enthusiastic.) Beyond that, Danny Says sticks to archival photos, videos, and talking heads (and, at least once, archival photos and videos of Talking Heads). It effectively makes the case that popular music would have been considerably different without his enthusiasm and support. He’s described by friends and colleagues as both a catalyst and a midwife, helping spur on and birth music that unquestionably had a lasting impact. If he had done that with a little less brio (and maybe more tact), Danny Says wouldn’t be nearly as fun. Then again, if he were a guy with a little less brio and a little more tact, he probably wouldn’t have had the impact he did.