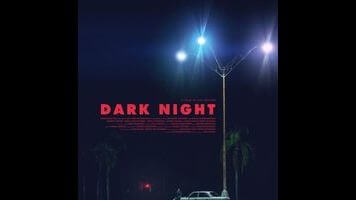

How soon is too soon? It’s a question that hovers around any movie that mines horrifying headlines for material. Back in 2003, Gus Van Sant risked hasty exploitation with Elephant, shaping the details of the Columbine massacre into a controlled, unsettling meditation on violence; the film provoked plenty of heated debate about representation, partially because it arrived when the atrocity it evokes was still fresh in the national consciousness. Now comes Dark Night, another enigmatic art movie being released about four years after the mass shooting that inspired it. One could certainly accuse writer-director Tim Sutton of too quickly depicting the events of July 20, 2012, when a gunman opened fire on a packed crowd at an Aurora, Colorado movie theater, killing 12 people and injuring many more. But the very concept of respectful distance has been hopelessly complicated in the years since Columbine. Simply put, mass shootings happen so frequently in America that it’s now impossible for a movie about them not to echo some real and recent tragedy.

Timeframe isn’t the only link between Van Sant’s movie and Sutton’s; the Elephant influence can be felt in everything from the elegance of the filmmaking to a closing shot of a cloudy sky to the queasy feeling that comes from watching a bunch of people go about their daily business, blissfully unaware of their impending death. Driven by the hazy blues noodling of Maica Armata’s guitar score, Dark Night unfolds over a single, lazy summer day that will only look significant in retrospect, following a group of mostly unnamed strangers during the mundane run-up to the rampage that will inevitably link them. Two kids skateboard around town. A young woman hangs out with her cat and snaps a few selfies. A military veteran attends a support-group meeting. Among these ordinary citizens, nearly all of them played by unknowns and nonprofessional actors, a disturbed young man (Robert Jumper) plans something terrible.

To call this a dramatization of the Aurora shooting wouldn’t quite be accurate. For one, Sutton, who previously made the atmospheric Willis Earl Beal vehicle Memphis, isn’t especially interested in drama; there’s not much plot connecting his observational vignettes, and no “arc” for his individual characters beyond an inevitable march into the dark night (and to the Dark Knight) of the title. Beyond that, the film deliberately fictionalizes its disturbing events by splicing in televised news footage and radio reports of the bloodshed in Aurora; the point may be that these shootings are now happening on top of each other, to the point where they seem to blur into a single scream of horror. That’s not the only choice that bends the reality of Dark Night’s world. The film’s dreamy naturalism is occasionally interrupted by faux documentary discussions with a troubled teenager, encouraged by his mother and an offscreen interviewer to talk about his feelings. These passages bridge the gap between opposing sides of a rigorous public debate: Maybe we need more thorough background checks and better communication with the damaged people who might commit such crimes.

A thick cloud of dread hangs over Dark Night, its violence teased from the striking opening scene, wherein the pulsing colors emanating from a movie screen—and dancing across someone’s eyes—are replaced by the flash of police lights. (Sutton loves these kind of transitions; he finds sonic equivalents, too, like the way the buzz of street lamps fades into the low chirp of crickets.) At times, the film’s relentless foreshadowing flirts with cheap shock-thriller tactics: A fake-out involving shrieking teenage girls in a parking lot is foul play, and Sutton beat Jackie to the punch with even crueler before-and-after mirror shots, bending the chronology to remind us that one woman’s fun night at the movies is going to go horribly awry. But Dark Night also twists certain suspense tactics to its thematic advantage; in its identification of several possible “suspects,” at least two with access to firearms, the film makes a powerful (if sidelong) case for stricter gun-control. After all, in a culture where anyone can get their hands on a weapon, everyone could be the shooter.

But Dark Night isn’t really a polemic. It’s a mysterious elegy for a community on the verge of a nightmarish crucible. Working with cinematographer Hélène Louvart, who provides both intimate close-ups and foreboding overheard overviews of the boxy suburban setting, Sutton exhibits a maturing eye for the tranquil beauty of middle-class American neighborhoods. His film would work as a haunting mood piece even if the violence never arrived—and in a sense it doesn’t, because the movie, unlike Van Sant’s spiritual ancestor, stops short of plunging us entirely into the carnage. Which is to say, while Dark Night is an uncomfortable film to experience in a movie theater, for obvious reasons, it manages to preserve the sanctity of that space, even while pivoting around the actions of someone who shattered it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.