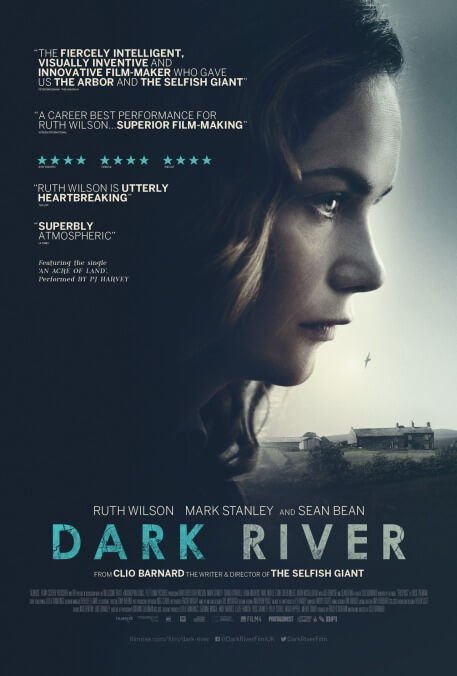

Dark River elevates generic drama through the sheer force of its conviction

A familiar tale told with intense conviction, Clio Barnard’s Dark River depicts two adult lives still caught in the undertow of childhood trauma. Alice (Ruth Wilson) has just returned to the English farm where she grew up, having spent the past 15 years as an itinerant worker all over the globe; her father recently died, leaving her tenancy rights to the family’s badly run-down property. Or so she believes. Her older brother, Joe (Mark Stanley), who took care of Dad solo during the old man’s declining years, understandably feels a certain possessiveness about the home he never left, and no small amount of resentment toward Alice. He initiates a competing claim that would allow him to evict her and sell off the farm’s assets, setting off a war of attrition—one that’s heavily complicated by Alice’s and Joe’s respective memories of what happened in that house many years earlier. Alice, in particular, experiences what are essentially PTSD flashbacks to those nights when her father (Sean Bean) would make his way to her bedroom.

This is surprisingly generic territory for Barnard, whose superb feature debut, The Arbor (2010), employed actors lip-syncing to documentary audio—a borderline avant-garde technique, at least on screen. (It has a more extensive history on stage.) Her sophomore effort, 2013’s The Selfish Giant, was more conventional, but still offered a wealth of specific details that made it feel unique. Dark River, by contrast, hits more or less the notes one would expect from its premise, which has fueled many an indie drama over the years (especially back in the late ’90s, when sexual abuse seemed to lurk in almost every protagonist’s past). Part of the problem may be that Barnard started out writing an adaptation of Rose Tremain’s 2010 novel Trespass, but wound up eliminating several of the book’s major characters and much of its flavor. (Tremain gets an “inspired by” credit.) What remains, while more direct, seems insufficiently rich or complex, hinging mostly on Alice and Joe avoiding the inevitable confrontation about the horror she experienced.

At the same time, though, Barnard’s sure hand with actors and intimate understanding of rural England are still very much in evidence. Wilson, who did sublimely creepy work in the title role of I Am The Pretty Thing That Lives In The House, ramps up the anxiety as a woman haunted by remembered helplessness, moving around every room as if constantly anticipating an assault. (Sean Bean, who appears in flashbacks, doesn’t really get much to do here apart from lurk with implicit menace, but does cleverly avoid being killed in this movie by virtue of playing a character who’s dead before it even begins.) Stanley, best known as Jon Snow’s buddy Grenn on Game Of Thrones (“And now his watch is ended”), vividly communicates Joe’s maelstrom of emotions upon Alice’s return, some of which don’t become comprehensible until we see what he saw, and badly misperceived, many years earlier. Throw in expert use of a picturesque yet oppressive location and Dark River almost manages to overcome narrative inertia via sheer force of will. It’s a beautifully crafted, moodily evocative film that’s missing just one spark of true inspiration.