It’s not really spoiling anything to acknowledge that the Swiss visual artist H.R. Giger wasn’t long for this world when he participated in filming Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World. Though there’s a twinkle in his eye on occasion, the Giger of 2013 and 2014—he died in May of that year—never seems terribly interested in talking about himself or his work, so much of the documentary sort of follows him around his house, hoping that something telling or profound will spill from the brain of the man whose dense, intense art clearly inspired so many.

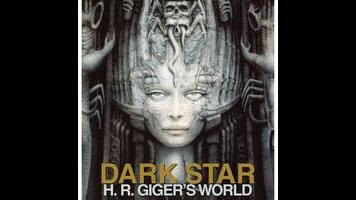

Giger’s house actually tells far more about the man than his own few words: It’s overstuffed with the artist’s work and memories, with every wall and corner covered with a drawing, a stack of books, or a random bone. That’s how Dark Star begins, with Giger literally fondling a human skull—the first he ever owned, as a child—and talking, very briefly, about his lifelong fixation with death and its emergence in his art. When the documentary tries—mostly with slightly inappropriate, macabre music—to make this sweet-seeming, time-damaged man more fascinating and dark on the surface than he actually is, it’s a bit of a slog. When it turns attention to his work—which is, no question, fascinating and groundbreaking—it finds surer footing. Giger’s paintings, drawings, and sculptures are almost exclusively concerned with the intersections of sex, death, and machines; his most famous pieces are of monochromatic “biomechanical” creatures that blur the line between the built and the created. They’re creepy as hell, and there’s no mistaking them for work by any other artist.

But Dark Star probably doesn’t do enough for the average viewer, who’ll no doubt know Giger mostly (or only) as the man behind the appearance of Ridley Scott’s Alien. After being passed a book of Giger’s artwork, Scott hired Giger to help design much of the film’s look, including the Alien itself. His work won Giger an Oscar, which sits dusty on a shelf in his overstuffed house, no more important than various books or pieces. The film touches very briefly on the idea that Giger gaining Hollywood fame brought him down in the “legit” art world, though it’s depicted as little more than a bump in the road that would eventually lead to art shows, awkward autograph sessions, and the H.R. Giger Museum.

What’s perhaps most telling about the artist himself is a later-in-life project he builds in his cluttered backyard, a sort of funhouse ride through his own psyche: It’s a tiny train that seats one, and it wends through foliage, sculptures of fetuses, and walls that look like viscera. It’s the only moment in Dark Star when Giger seems to be enjoying himself, letting the lightness of his personality—some of which is also seen briefly in archival footage—come through. It’s an odd bit of humanization in a film that otherwise seeks to mythologize him. But on the whole, Dark Star feels like only a partial portrait, not exactly a biographical history of an important artist or a glimpse into his soul.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.