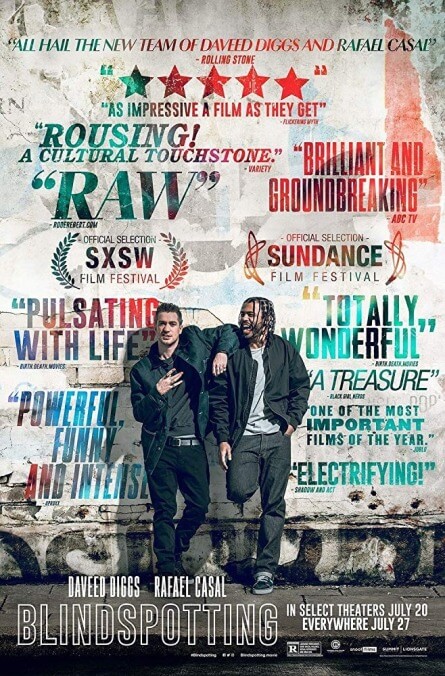

Daveed Diggs blends comedy, drama, and a portrait of Oakland in the impressive Blindspotting

If the recent Sorry To Bother You presents a head-trip, music-video vision of trying to get by in Oakland, California, then Blindspotting offers a more grounded tour of the city, addressing some of the same or related problems: racism, gentrification, systemic oppression. Given the proximity of the two movies both at Sundance and in general release this summer, Blindspotting has every opportunity to look more staid, earnest, and traditionalist in its approach to the subject matter. As it turns out, this may be why such a small-scale, sometimes predictable drama can still feel, at times, downright revelatory: It crackles to life without a surfeit of surface flash.

That’s not to say that Blindspotting lacks style or energy. Director Carlos López Estrada indulges in quick-hit close-ups but also frequently lets his camera just linger on best friends Collin (Daveed Diggs) and Miles (Rafael Casal) as they walk around Oakland or goof on each other in a locker room. Despite the jocularity, Collin has to be cautious. He’s staring down the last three days of probation, eager to leave his curfew-dependent halfway house and maybe rekindle his relationship with Val (Janina Gavankar), who also works the front desk at the moving company that employs both Collin and Miles. Collin sometimes has to cover for Miles, who will show up late to work or curse out a well-to-do Whole Foods shopper too focused on his phone to notice when he’s blocked the moving truck in. More urgently, Miles is the type of friend who will buy an illegal firearm out of a car with his on-probation buddy along for the transaction, very much against his will.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.