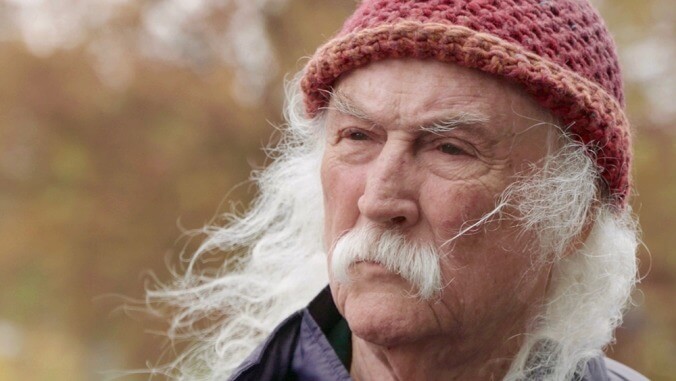

David Crosby somehow lived long enough to get the overdue documentary treatment

By all rights, David Crosby should’ve died sometime in the 1980s. From his emergence in the mid-’60s as a guitarist and vocalist for The Byrds to his stadium-filling days as part of the supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the singer-songwriter never denied himself any of the excesses of his era. Wanton sex? Sure! Extremist political views? Absolutely! Drugs? What are you holding?

If Crosby had been felled by, say, an overdose, it’s hard to say what his legacy would be. The critical reputation of Crosby, Stills & Nash declined after the band’s second album (more or less once Neil Young decided he didn’t want to be a permanent fixture). And in the punk and New Wave eras, cranky old hippies like Crosby were regarded as a joke. Plus, as the man himself points out in the documentary David Crosby: Remember My Name, he was the one guy in CSNY who never wrote a big chart hit.

And yet Remember My Name captures Crosby on an unlikely high, no pun intended. Here in the late 2010s, Crosby’s off hard drugs, he’s happily married, he’s touring regularly, he’s a Twitter favorite, and he’s been releasing acclaimed solo albums at a steady clip for much of the past decade. On the other hand, he’s also feuding with most of his closest colleagues and—again, in his own words—as he approaches his 80th birthday he finds he still has to work year-round to buy groceries and pay his mortgage.

Eaton’s film is built around multiple interviews conducted by former Rolling Stone reporter (and pretty good filmmaker) Cameron Crowe: some shot in Crosby’s home, and some shot in the Los Angeles area, where Crosby drives around and talks about the respective rock ’n’ roll heydays of Sunset Strip and Laurel Canyon. From those two scenes came some of the most vital music of the 20th century—The Byrds, Joni Mitchell, Buffalo Springfield, Cass Elliot, and more—and Crosby was intimately acquainted with all the major players, as a pal, a partner, a collaborator, or a lover. And one of his greatest weaknesses as a friend is one of his greatest strengths as a public figure and a documentary subject: He’s brutally honest, not just about his own mistakes but others’.

Remember My Name is a bit too thin when it comes to analysis and appreciation of Crosby’s actual music. There’s very little commentary about his style or technique, from critics, contemporaries, or Crosby himself. The first anecdote in the film is about how he was captivated as a young man by the intensity of John Coltrane. And from the start, what set his songs apart from other folk-rockers was the extent to which he drew on jazz, classical, and the avant-garde. The movie takes its name from Crosby’s first solo album, the 1971 masterpiece If I Could Only Remember My Name, which eschewed the pop concessions of The Byrds and CSN and just dedicated 37 minutes to pretty harmonies, mesmerizing rhythms, and the many different sounds a guitar can make.

Eaton’s documentary covers the making of that record at some length, but is less interested in its musical innovations than in its all-star team of guest musicians (including Mitchell, Young, Nash, and most of The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane), and in the personal crises Crosby was going through at the time. The choice to focus on Crosby’s troubled relationships and drug abuse throughout Remember My Name makes sense from a marketing perspective. For many casual viewers, the messes that Crosby’s made over the past 50-plus years are far better known than his songs like “Guinnevere” and “The Lee Shore.” But fans already convinced that Crosby’s one of the greats may be let down that the film doesn’t attempt any kind of scholarly deconstruction of “Tamalpais High” or the like.

That said, Remember My Name still works magnificently as a tragicomic character sketch, lead by a man who started burning bridges back when he was with The Byrds, when he’d hijack the band’s concerts to rant for minutes about who really killed JFK. (“David became insufferable,” sighs Roger McGuinn, who’s one of the few Crosby bandmates who appears in new interview footage, rather than archival clips.) Friends who stood by him during his worst moments won’t talk to him now, because even after he sobered up, and straightened out his family life and his musical career, he still tested people’s patience. “My biggest fuckup is getting mad,” Crosby says with weary resignation at the end of Remember My Name.

“I’m afraid of dying,” Crosby also admits, early in the film. “And I’m close.” Twenty or 30 years ago, the inevitably of that death might’ve taken some of the sting out of it, even for all those people who’ve worn the grooves down on their copies of the first Crosby, Stills & Nash album. But as Remember My Name makes clear, Crosby today is closer to having a happy ending to his life story than he’s ever been—if he can only stick around long enough to heal all the old wounds.