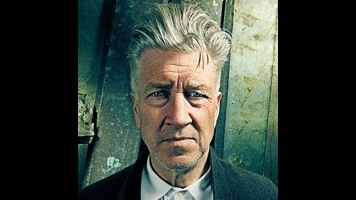

David Lynch: The Art Life is as close a look as the director has ever allowed

Lots and little of David Lynch are on view in The Art Life, as is so often the case. For the filmmaker behind enigmatic masterworks like Eraserhead, Mulholland Dr., and the cult series Twin Peaks—whose upcoming revival makes this new documentary from Janus Films especially timely—ambiguity tantalizes in a way linear storytelling never could. That vagueness typically extends to Lynch himself, whose reserve in interviews matches the elusiveness of his movies, which so often proves frustrating to anyone digging for some tidy, armchair psychologist’s interpretation of the Freudian nightmares in his work. Lynch usually demurs that he’s just a vessel for his many unsettling creations, comparing their genesis to catching fish or putting together puzzles whose pieces have been flipped over one by one for him—presenting himself as merely the interpreter of notions received from some mystical source, and all but removing himself from the process. But because this assertion belies what is clearly one of the most recognizable authorial voices in cinema, it rarely satisfies. Critics, fans, and interviewers keep probing Lynch in hopes that, eventually, he will confess to the many emotional traumas that must surely be roiling just below his serene, folksy surface.

The Art Life comes as close as anyone ever has to cracking that. Directed by Jon Nguyen—whose 2007 documentary, Lynch, tracked the director while he assembled Inland Empire, and who, along with Olivia Neergaard-Holm and Rick Barnes, spent four years compiling the audio interviews that serve here as narration—it’s a notably more intimate study of the man, rather than his movies. In fact, anyone looking for behind-the-scenes clips or anecdotes will leave disappointed: The film assumes an audience familiarity with his oeuvre that will fill in the subtext behind its various insights into Lynch’s impulses. What it offers is a more personal chronicle of Lynch’s formative years, told through extensive use of old photos and home movies, that ends just as he’s beginning to put together Eraserhead.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.