David Morse on Outsiders, The Long Kiss Goodnight, and The Rock

Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

The actor: When David Morse started his acting career in the 1970s, it was with an eye toward theater, but after kicking off his on-camera career with a role in the 1980 film Inside Moves, he followed a path that soon led him down the hallowed halls of St. Elsewhere, where he remained through the end of the series’ sixth and final season. Since then, Morse has continued to shift back and forth between television and film, appearing in action blockbusters (The Long Kiss Goodnight, The Rock), cable dramas (Treme), and even the occasional primetime sitcom (Big Wave Dave’s), accruing more than enough credits to warrant a sequel to his Random Roles interview from 2008. Currently, Morse can be found within the ensemble of WGN America’s latest drama, Outsiders, which airs Tuesdays at 9 p.m. Eastern.

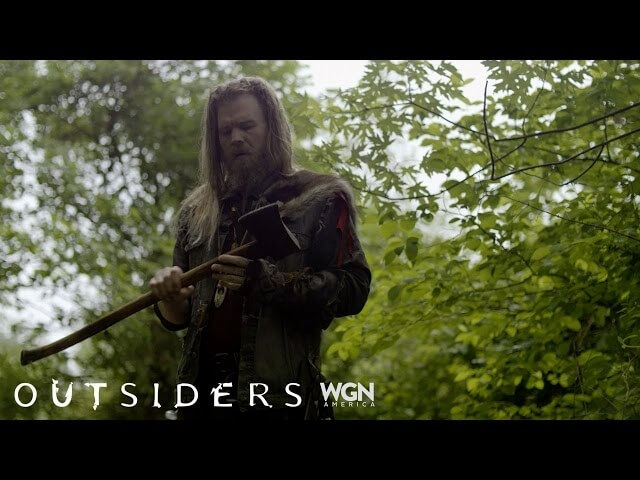

Outsiders (2016)—“Big Foster”

David Morse: I guess they came to me with the pitch, although it was a little different than some roles that come to me. Paul Giamatti and I have the same representatives, the same manager—we’ve been with Perri Kipperman for a long time—and his company was part the process of developing this show and getting it to WGN. But I didn’t hear anything about it or know anything about it until the call I got saying that I’d been offered the role of Big Foster and that Paul was an executive producer on it. So just hearing that he was involved, that was interesting, but also that it was on WGN, because I have a friend who’s a writer and executive producer who’d been developing a project with them. He’d been talking to me about it, so I was aware of them and that—like a lot of places—they’re looking for really different material, and when they choose something, they really commit to it. They do 13 episodes. So there was a lot of good already before I even got the script.

The A.V. Club: How would you describe Big Foster?

DM: Well, just in terms of when I got the script, the character I probably liked the least was Big Foster. Because even though he was central to the story and to that world, he was really written to be kind of a brute, a pig, a completely black-and-white bad guy. And I really wasn’t interested in just doing that, so I asked if I could talk to Peter Mattei, the creator. And we did talk, and we had a very good conversation. He was feeling like myself—that even though he was involved in creating it and writing it, seeing the scripts that he’d written and seeing the character, he felt there could be a lot more there as well. So we talked about him in terms of a real human being, and what his past was, and what he really wants from the world.

So Big Foster is a guy who was in line to be the head of this clan that’s been up in the mountains for 200 years, because his father was the leader or the Bren’in, his mother is now Bren’in, and they’re kind of royalty, so he was in line to be next, he’d been promised it from a young age, but it just hasn’t happened. And while he’s waiting, he’s become this sort of playboy drinker, getting away with anything because of who he is, and he’s kind of rotted inside. Anything that was good about him has really sort of been poisoned. The one thing that he is keenly aware of is the danger that their community is in, that their world is in, from the coal company. And because of his past, he probably understands better than anybody the real danger they’re in, and he’ll do anything to protect them.

AVC: People who don’t know anything about the series but just see the publicity photos of the characters on motorcycles are likely to think of Outsiders in the same terms as Sons Of Anarchy. Would you say there are any parallels?

DM: Well, I’ve never watched Sons Of Anarchy, so I’m not a good one to ask about that!

AVC: Well, just speaking in general terms, Sons Of Anarchy certainly had some Shakespearean elements, which Outsiders looks to have as well.

DM: Well, I think as the season went on, people started feeling more and more like my character is a King Lear kind of character. And I know when I was researching and preparing for the role, because of the language that we use—the old tongue—and some of the rituals that we have, I was actually reading Shakespeare and looking through Shakespeare just for the language, using that as well as Native American stuff. That, and watching documentaries about people who live up in the mountains, and that kind of thing. So for me, I can’t really compare it to Sons Of Anarchy, because I don’t know, but certainly there are feelings in the stories of these characters that are out of Shakespeare.

Inside Moves (1980)—“Jerry Maxwell”

AVC: By all reports, it would appear that your first on-camera role was in the film Inside Moves.

DM: That’s correct, yes. I’d never done any film or television. Well, I’d done one little stupid commercial in Boston when I was doing theater, but that was it.

AVC: Did you make an overt attempt to jump to on-camera work from theater, or was it just that there was an opportunity there and you took advantage of it?

DM: Well, because I’d only done theater, that’s really what I thought most of my life would be. I always figured that movies would be a part of it at some point. I didn’t know how or when. When I was in New York—I’d gone from Boston to New York—I studied with a man named William Esper for a couple of years where I wasn’t really doing any acting during that time. A little, but not really anything. And pretty quickly after that, I was just going out to do plays. I wasn’t even really pursuing an agent or anything. I just figured, “If I can do theater, agents will find their way.” And I was doing a play and met my first agent, Jane Feinberg, and she really was just getting me out to meet any casting people coming to New York. I went to audition for The Dogs Of War, which Christopher Walken was doing, and Mike Fenton, Jane’s partner, was casting that, and they offered me the role in The Dogs Of War, but she called Mike Fenton, who was also casting Inside Moves, and said, “You have to see this guy.” And I wound up seeing them the next day and screen-tested, and I ended up doing my first film!

AVC: The majority of your work was with John Savage. How was he to work with, given that you were a first-timer?

DM: Well, John Savage, I thought it was maybe some of the best work that he ever did. I thought he was great at that time, anyway, from the movies he’d done, like The Deer Hunter, Hair, and The Onion Field. So I was kind of a little bit in awe when I first met him and realized I was going to be starring in a movie with him. [Laughs.] But even the screen test… When I tested, I did the screen test with Ellen Barkin, and she was this hot young thing in New York. John Shea was there, and he was a big star in the New York theater at the time. He was the hot guy. So just to be in that world, going from where I was, which was really straight out of an acting class and doing a lot of theater into being around all these people, it really was another world for me. John was fantastic in that movie, but so was everybody in that movie, that whole collection. It was really an ensemble movie, even though we were kind of the leads in it. When you watch that movie, it truly is a great ensemble, and it really kind of set the stage for a lot of things I’ve done. You know, a lot of the things I’ve enjoyed the most and that I think have been the best are ensembles.

AVC: So how did you find your way into acting in the first place?

DM: Well, for a lot of people, if they’re lucky, it begins with somebody who recognizes something in them. When I was in school, in eighth grade, someone recognized something in me. She was an English teacher, and we read a play out loud in class, and she asked me to read one of the roles. I’d never done anything like that before, but something just lit up. And then when I got to ninth grade, there was another teacher who was the head of the drama department, and it was the same thing: she just recognized it. And then I went right from high school at 17 years old to a repertory theater in Boston. You know, it’s not something I looked for. It’s just something that really awoke in me, and there was nothing else I wanted to do.

16 Blocks (2006)—“Det. Frank Nugent”

AVC: You worked with Richard Donner a few other times after he directed you in Inside Moves, first on Two-Fisted Tales, and then later in 16 Blocks.

DM: I love that man. Working with him on 16 Blocks and Two-Fisted Tales—on Inside Movies, he really set a standard for how you treat people, how you create a family when you do work. You know, he’s a very big-hearted man, and when he gathers a company together, they become his family, and he treats them like a family in the best sense. I’ve been in productions where they are like family, but the most dysfunctional family you’ve ever been in. [Laughs.] And you want to get out of it! But he is really a good guy and I think a really, really fine director. When he has really good material, he’s really a fine director.

AVC: You’ve averaged a project a decade with him. Maybe you can lure him out of retirement for another go-round on something.

DM: Boy, wouldn’t that be great? Because, yeah, I think 16 Blocks was the last movie he did.

Homicide: Life On The Street (1995)—“Jim Bayliss”

Treme (2010-2013)—“Lt. Terry Colson”

DM: I had worked with Eric Overmyer when he was one of the writers on St. Elsewhere. He was there for a little while. I don’t think he felt comfortable there, but he was significant while he was there. And I did Homicide later—just an episode—with David Simon, so I had a little experience with the two of them. When they were putting together Treme, there was a role in there that John Goodman played, and I was asked to go in and talk to them about that role. So I went in and spent a good amount of time with them talking about it, my feelings about it and all that, and David Mills was there, who wound up dying during [the making of] that first season. When I left the meeting, I thought, “You know, this went really well,” and I really sort of expected to get the role… and I didn’t get the role, I didn’t hear anything, and I was really kind of disappointed. And a little bit hurt.

But then I was doing a movie with Martin Donovan called Collaborator up in Canada, and I got a call saying, “David Simon wants to talk to you about a new role on Treme.” Treme hadn’t come out yet, so there was nothing to see, so I didn’t know how the show turned out or anything. But David and I had a conversation, and he said he had a scene that he wanted to send me. He didn’t have anything else on the character, he just had a scene, but he wanted to bring the character into the show specifically as having a relationship with Melissa Leo’s character, which… I had known of Melissa, met her, and seen her on Homicide, which I thought she was fantastic on, so I kind of knew some of her story. And I thought, “Well, this’ll be interesting.” And David had done The Wire, which may be one of the greatest things that’s ever been on television.

I kind of had to go on faith. All I had was a scene and what David said about the character of Terry. He said I had to understand that it was a show about New Orleans, it wasn’t a show about police, so that wouldn’t necessarily be what the stories were about. But I thought, “How many opportunities are you going to have to work with David Simon and Eric Overmyer? Let’s just go for it and see where it takes us.” And almost four years later, we were finishing up the show.

The Hurt Locker (2008)—“Col. Reed”

DM: The Hurt Locker was one of those things that wasn’t much of a role, but Kathryn [Bigelow] was looking for… [Hesitates.] I shouldn’t say “wasn’t much of a role.” It was a really fun role, but in terms of screen time, there wasn’t a lot there. But her idea for that film was to have these relatively unknown lead characters who are really fighting for their lives and in incredible jeopardy, and then have these other characters, played by Guy Pearce or Ralph Fiennes, who you’ve seen in bigger roles in other movies, play these smaller things, and you keep thinking, “Okay, here’s the people who are gonna save the day and take control!” But the characters that Guy and Ralph play obviously don’t do that. I thought that was kind of a cool idea, to have these significant cameo roles with these people who you really don’t associate with anything other than that.

I knew Jeremy [Renner] from the movie Dahmer. He and I had both worked with the same director, so I knew his work from that and I knew he was terrific. And I was excited to work with Kathryn. I thought it was a great script. So it was an adventure, to get to go over there to Jordan. I felt connected to it because my great-grandfather spent a lot of time there. He knew the king of Jordan at one time, and I have a little pocket knife, this gold-inlayed pocket knife, that he gave my great-grandfather, and my great-grandfather gave it to me. So I’ve always felt sort of a connection to Jordan, so to actually get to go there and see it and work there was a great opportunity. It had a lot of meaning for me.

Twelve Monkeys (1995)—“Dr. Peters”

DM: I had just moved to Philadelphia. We had just lost our house in the earthquake in Los Angeles, we’d just moved, our lives were very unsettled, and we didn’t know if we were going to live there or—well, we didn’t know where we were going to live, but we’d kind of landed there to figure out our lives. I got the Twelve Monkeys script, which was at that time—and probably still is to this day—one of the most amazing scripts I’ve ever read. You really could not figure out where you were in that story until the very end. Again, it was one of those roles that so jumped off the page that, even though it wasn’t a huge role, it was so central to that whole story, and it was such a colorful character. And then there was meeting Terry Gilliam, who was a colorful man, for sure, and I’d loved his films. Again, with all those things, you ask, “How many opportunities am I going to get like this?” So I went for it, and I’m glad I did.

AVC: How did you find Gilliam as a director?

DM: He has a great consciousness, along with his great visual sense and his unusual choice of stories and films to make. He would walk around the city, and it would feel like he’d seen things around the city that people who lived there didn’t see, whether it was homeless people or corners of the city where, unless you lived there, you wouldn’t know them. And he was dealing with two phenomena at the time: Bruce Willis was at the height of his stardom then, and Brad Pitt was just becoming a star, so he was balancing the two of them. Brad Pitt would be kind of sitting in a corner unless there was a party and kind of hiding, and then he’d go outside and there’d be girls out there screaming. And Bruce, he was a movie star, living the big movie star life, with all his movie star quirks and demands. I was very taken with Terry and how he balanced those things while making the movie.

Our Family Business (1981)—“Phil”

DM: [Uncertainly.] Our Family Business? Are you talking about the pilot?

AVC: That’s the one.

DM: You’re really stretching here.

AVC: We can just skip to the next one if you don’t have anything to say about it.

DM: Well, no, I sort of do. I didn’t want to do television at all. I really didn’t want to do it. I really thought I was just going to be doing theater and doing movies. And after I did Inside Moves, having gone from doing no movies or television to suddenly starring in a movie and now competing with people like John Travolta for work, I was just at a level that I was completely unaccustomed to. And people didn’t really know me, because Inside Moves… The distribution company went bankrupt as soon as the movie opened, or two weeks after it opened, and it was pulled from the theaters, and there was no video to speak of or anything else yet, so nobody had seen the movie. And yet here I was competing with all of these movies stars and not getting work. And I wound up broke and running out of unemployment and running out of borrowed money, so I said “yes” to a pilot.

I went out and auditioned for this pilot that was supposed to be like—or was inspired by—The Godfather. It was supposed to be the Los Angeles mob, and I was the Al Pacino character, and Ted Danson, who was in it, was the Sonny, the James Caan character. He was the bad, bad boy, and I was the good boy, and Sam Wanamaker was our father. And it was… [Snorts.] Well, thank God nobody saw it. And thank God it didn’t become a series, because Ted went on to do Cheers, and I went on to do St. Elsewhere.

AVC: I thought it was interesting that the pilot also featured Ray Milland and Vera Miles.

DM: Ray Milland I saw at the other end of the table from me in one scene, and I knew he was somebody special, but I didn’t remember him from movies. I didn’t watch a lot of old movies. I wish he had meant more to me at the time—now I understand more about who he was—but I just kind of watched him down there at the other end of the table. Vera Miles, it was fun to have her as my mother. It was sort of surreal, after having seen her in TV for so much of my childhood, to actually have this woman playing my mother in a show!

The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996)—“Luke / Daedalus”

DM: I have so many people who still talk to me about The Long Kiss Goodnight, about that being one of their favorite movies, and it really was a fun movie. You know, with Samuel Jackson, who’d just begun really taking off, and Geena Davis. I just thought it was terrific. There were a bunch of things that happened all around the same time—there was that, The Rock, Extreme Measures, and that one… I auditioned with Geena, who I really liked, and it felt like we had something happening together. And I guess something was happening, because I got the job! [Laughs.]

There’s a scene in there where I try to drown her, and she’s on that water wheel, this big thing, and she’s going underwater. It was amazing. I mean, Renny Harlin just does everything big. And when that scene was shot, I think he had something like 11 cameras going on all the time. To shoot that thing, I think it took three days, with these scuba divers underwater so that, when she went underwater, they’d give her air, and then she’d come back up. So it was all on her for three days. And then at the end of the third day, they sent her home at midnight, and they turned a camera on me. And I had to do the scene all by myself with a script supervisor but with nobody else there, and everybody was exhausted and just wanted to go home. It was not very satisfying. It’s kind of the worst of movie-making. And I can’t personally watch myself in it, because all I think about and all I see is that kind of stuff: me trying to pretend that somebody’s out there. It just makes me cringe. [Laughs.]

The Rock (1996)—“Maj. Tom Baxter”

DM: I was doing a one-person play in Los Angeles called An Almost Holy Picture at the La Jolla Playhouse, I had an afternoon off or something, and I had gotten the script for The Rock. I don’t think Ed Harris was in it yet—I knew that Nicolas Cage was in it, and Sean Connery—but I went up and met Michael Bay and read with him, and Michael… [Hesitates.] Everybody knows that Michael is… Well, he’s really a tyrant on the set. There’s a lot of directors who do this, who have a reputation for this, where they yell at everybody and it’s like nobody can do anything right. But when you meet him in person, you know, he couldn’t be nicer. I’ve worked with a few directors like this, who—once they cross the threshold onto the set—it’s like a Jekyll and Hyde kind of thing. And Michael is one of those people. So I had a great meeting with him and a great time, and I liked him, and I got offered that role.

Originally my character was the bad guy who went all the way through the story, even into the climactic battle with Nicolas Cage, so I was looking forward to that. When I got there for the first read-through, Sean Connery was there and Nic was there. Everybody was there—Ed Harris was now there—but I was no longer the bad guy. I was now a good guy. Even though I was part of the team, I didn’t go all the way through to the end. You’d think somebody would’ve told me that I wasn’t playing the same character that I thought I was! But apparently that wasn’t important. But we had a pretty good read-through, and then we got to go out and play with the Navy SEALs that were on our team, and suddenly this movie became really cool. [Laughs.]

We spent two weeks with the Navy SEALs, and these guys are fantastic. And they were really into doing this movie. I think in a lot of ways those Navy SEALs, what they brought to it was the heart of that movie. Even though Nic was great and Ed was great and Sean Connery was great, really, the real heart of that movie to me was the authenticity that these men brought to it. And to get to spend those two weeks with them, and then spend all the time on the set with them out on Alcatraz—two months or whatever it was—and then two months on a stage in Hollywood… I really admire those guys, and I’m grateful to them for what they brought to that movie.

Extreme Measures (1996)—“FBI Agent Frank Hare”

AVC: As long as we’re in the ’96 zone, if you’ve got any sort of Gene Hackman story from working on Extreme Measures, we won’t turn it down.

DM: I don’t know if I have a Gene Hackman story, but I think it’s the only drama that Hugh [Grant] has ever done. He just got so burnt by it that he never did another one! [Laughs.] He and Elizabeth Hurley were producing it, and Michael Apted—who’d been directing forever and is one of the great film directors—he was kind of caught between the producer Hugh and the star Hugh, and that’s a tough place for a director to be, as far as how to negotiate those two people in one. You want to be able to direct your star, but he’s also the producer, and he’s watching the whole thing, and he’s watching you, the director. I hadn’t really been around that before, and I think it’s an uncomfortable situation, not just for the director but also for us on the set as well.

Sarah Jessica Parker, she was on there, and she was really being an actress. She had dyed her hair brown and made herself kind of mousy, and I don’t think she’s ever done that again in her life, not after Sex And The City. I thought that was interesting, because I’d seen her on a couple of series, and she’s another person who I thought was really good, but to see her go for it like that… I mean, not just for her, but for actresses in general, I think that’s really risky to make yourself unsexy, because the business demands that women be sexy. I liked it that she did that in the movie, although I think it’s interesting that I’ve never seen her do that again. Maybe she did. I don’t know.

But Gene… I had a few scenes with him. I had auditioned for a movie that he did awhile before that—Andrew Davis directed it, and Tommy Lee Jones wound up getting the role—but he had heard that I might be getting the role, that I might be doing the film. Well, I wound up not doing it, but we ended up just meeting on the street—he was out walking his dogs—and we talked for a little bit, and he said at that time that he was ready to retire. He thought that maybe he was going to do another film, maybe a couple more films. And 10 years later, he was still doing movies. [Laughs.] You know, I think he’s an actor like all of us: as long as people are hiring us, no matter who you are, we’re all afraid that the job you’re doing is the last one you’ll ever do. And even at that time of his life, I think there was probably part of him that thought that if he really did retire, and then he decided that he wanted to come back, they might not have welcomed him back, or there might not be roles for him. And that little insecurity probably kept him going for another 10 years.

Bait (2000)—“Edgar Clenteen”

DM: You know, that was a fun movie to do. I had done The Green Mile for Castle Rock, and they asked if I would do it. Kris Kristofferson was originally going to do the role, but he dropped out at the last second, so they called and asked if I would do the movie. And I read the script, and there was a lot of comedy in it—you know, obviously, it had Jamie Foxx—but Clenteen was the only character who was not funny. [Laughs.] And I thought, “I don’t want to be the only unfunny guy in this movie. I really would like to be somehow involved in the comedy if I’m going to do it.”

So I went and talked to the director, the writer, and the producers at Castle Rock, who I’d met while I was doing The Green Mile, and I said that to them. I said, “I’d love it if you could find some stuff.” And they said, “Well, we can’t really change the script, because it’s so close to when we’re going to shoot.” I think we had two weeks or something. “But we’ll do the scenes that are there, and then we can add some stuff at the beginning and at the end of the scenes, and then we’ll have it.” Well, I fell for that. [Laughs.] So the little things that we did at the beginning and end of the scenes, of course they cut all those things out, and all they had left was the original scene that they’d written. And my character was not funny or part of the fun.

But I’m glad I did the job. That’s another one of those films that, to this day, people—especially in the African-American community—say it’s one of their favorites. They love Jamie. And rightly so! I don’t know if it was the second movie he’d done or what, but he’s one of the funniest people that I’ve ever been around. He had an entourage at that time that did nothing but get him in trouble. I think at this point in his life he probably is living his life a little differently. But at that time, he was… Well, he liked to live his life. And, boy, could he get into trouble!

Big Wave Dave’s (1993)—“Dave Bell”

AVC: Speaking of being funny, Big Wave Dave’s is very much an anomaly for you, in that it’s the only time you’ve ever been a regular on a sitcom.

DM: Ken Levine was one of the creators of that, along with David Isaacs, and why they took a chance on me for that show, I don’t know. They were two of the writers on Cheers, and they had such status in the comedy world.

It wasn’t too long after St. Elsewhere, and I’d done The Indian Runner with Sean Penn at that point, but I wasn’t getting movies, and I needed money. Sean had asked me to do The Crossing Guard while we were doing The Indian Runner. He ran over to my trailer one day and handed me a scene and said, “Read this.” I read it, and I said, “That’s really cool.” He said, “I want you to play this role of Booth in here, but I don’t know what the movie is yet.” But over the next couple of years, he kept sending me scenes as the script was evolving. And I wasn’t really getting any other work that was paying—just a little bit—but I kept believing that we were going to do this movie. Harvey Keitel was supposed to do it, but he dropped out because he was a big shot at the time, and then Jack Nicholson said he would do it, but we had to wait a year. I was broke. And if I was going to have to wait a year for The Crossing Guard, then I had to audition for television.

So I auditioned for a bunch of pilots, I got offered every single pilot I auditioned for, and they were all dramas except for this Big Wave Dave’s. Nobody would ever hire me for a comedy… and suddenly these two guys were interested in me. And I had to go and test for the network and the studio and do that whole thing, which I hadn’t had to do for awhile, but it was a comedy, so I did it. And I got to do it with my friend Adam Arkin—I’d known him for a long time, and he’s a good friend—and we got to do six episodes.

Because I’d never done a comedy and I heard we were going to have rehearsals, I thought, “Fantastic! This will be like theater: we’ll do rehearsals, and then we get the day that we shoot it!” What I didn’t realize is that the writing process for comedies is that you do your table read, and if you aren’t funny on that first day during the table read, they take your jokes away and give them to somebody else. Or they change it. And the next day, when you do rehearsals during the day, all the writers come, and they all line up at the edge of the stage, and you have to perform for them. And, again, if you’re not funny, they take away your jokes and give them to somebody else. I went, “Wow, this is not the rehearsal process that I’m used to…” I thought the rehearsal process was, you actually get to work on things, and then when you’re in front of the audience, you get to be funny.

It was a little painful for me, that process, and by the sixth episode, I started getting into the swing of it, understanding that I can’t take all this personally, that they just want their jokes to work because this is a comedy, and we’re here to make them work. I wouldn’t mind having another shot at doing comedy, but I’m not sure that’s the way I’d want to go.

Prototype (1983)—“Michael”

AVC: This one seems destined to either make you laugh or groan.

DM: That one will only bring out fond feelings.

AVC: Oh, good.

DM: I don’t know why I’d groan about that one. [Richard] Levinson and [William] Link, who wrote that, were very esteemed writers in the television world. I didn’t know anything about them because I didn’t know television. I hadn’t owned a television for 10 years, so their names meant nothing to me. But it was during the period when we did the first season of St. Elsewhere. I was actually up in Idyllwild, in California, with my wife, and I had my kind of long hair from the show, and I heard about this role. And somehow I got the role FedEx-ed to me or something, and I read it. I’d heard it was going to be with Christopher Plummer, and I thought, “Well, he’s one of the great actors of our time!” So I drove back from Idyllwild early with my wife to do this audition, but I knew I had to be different for this role, and I knew I couldn’t go in with my hair long. So I stopped in Westwood and went into a random barber shop and asked them to cut off all my hair, and then I went in to do the audition. [Laughs.] And—obviously—I got the role!

I’ve been lucky to be involved with some very smart people and very smart scripts, and I thought this was a very smart re-telling of the Frankenstein story. It was even more in line with the original Frankenstein story than the movies we traditionally see with him as the monster, being kind of a sensitive and intelligent creature. And there was a lot of love in that movie. It truly was a movie about the love between the creator and his creation, and it’s an unexpected love for a guy who’s never had a son: his creation becomes kind of a surrogate son, and he can’t let him go to the military, who wants to use him as a weapon. I’m incredibly fond of that experience. I think it’s one of the best experiences I’ve had in the television world.

AVC: Just to clarify, the “laugh or groan” remark was based solely on the fact that I don’t think I’ve seen the movie since 1983, and sci-fi TV that seemed great in ’83—as Prototype did—hasn’t always aged well.

DM: [Laughs.] Yes, well, I haven’t seen it in a long time, either. All I know is my experience on it. But we got sent a DVD of it at some point, and although it’s about a sweet character and features this love story, the cover of the DVD is something like out of the movie Alien! You think you’re going to see some incredible horror character, and it couldn’t be further from that.

Desperate Hours (1990)—“Albert”

DM: I met [director] Michael Cimino—I think I was the second one cast in the film at that point—and I really liked him. I really liked spending time with him. And when he cast me in that role… You know, it was right after St. Elsewhere, and I really hadn’t done a movie in 10 years. I did an independent movie [Personal Foul], but after having gone from Inside Moves saying, “I will never do television,” I then wound up doing 10 years of television and almost nothing but that. So I was so happy to be able to audition for a movie and actually get a role, and then because I was cast so early, I did all the readings with all the other actors that came in after that, which was fun to do. I got to meet a lot of people and spend a lot of time with Michael Cimino. Along the way, Anthony Hopkins became involved, and Mickey Rourke—I believe he was already cast. I think he was the first one.

But we did this pre-shoot before anybody else got there, where it was just me. We did three days up in Zion National Park, where my character… There’s a sequence in there where, after we escape the house where all the things have happened, I somehow manage to run into Zion Canyon. I don’t know how I managed to do that with that character, but that’s where he wound up. [Laughs.] But this is one of the great things about filmmaking: it really can be an extraordinary adventure. And these three days really were an adventure, going way, way up, with just the DP and myself and the sound guy, plus somebody to carry the equipment. We went way up this river, up in the canyon, where the walls go straight up to 2,500 feet or something, and they were filming us running down there, and then the spectacular death that I had, out in the middle of the river, surrounded by horses. You know, Michael Cimino, he just thought big. He had just orchestrated this great scene, where I’m standing in the river, and the SWAT team is up so far on the cliffs that I can’t even see them, and I’m down there with the horses, and then the horses all disperse, and it’s me alone in the river.

I had a wetsuit on with probably 200 squibs in it where I’m gonna get shot, and the wetsuit is underneath my clothes, but I’d never done anything like this before. The stunt guy said, “Just stand up as long as you can while these things are going off. Just let your body loose, and let the squibs do all the work, and stay on your feet as long as you can.” And when I was shot, these 200 things come off and it jerked my body all over the place. I was supposed to fall down the river and float away, but it was pretty shocking when I fell down in the water and all that water went right down my back. It was like an electric jolt! And I shot out of the water, because it was so cold, and I just ruined everything. I ruined the entire shot. They were all thrilled. [Laughs.] But we spent the rest of the day with me floating down the river, getting hypothermia, while they shot up in the canyon from a half mile away. I literally wound up with hypothermia by the end of the day! But it was such an adventure. And it was a great experience with Michael.

But as soon as we got to the set in Salt Lake City and Mickey Rourke showed up, Michael transformed into a monster. Again, it was one of those things where a director is one way, and then suddenly you see this whole other thing. I think Michael has done extraordinary work, and I won’t take anything away from that, but that relationship that he had with Mickey at that time was so incredibly dysfunctional. And he couldn’t take it out on Mickey, because Mickey was the star, so he had to take it out on the rest of us—except for Anthony Hopkins. Tony. So overall it was not a very happy experience. But I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Magic Kid II (1994)—“Jack”

AVC: You discussed St. Elsewhere at some length the last time we talked with you, but something that wasn’t tackled was Magic Kid II, which was directed by Stephen Furst and features appearances by William Daniels, Howie Mandel, and yourself. The best part, though, is that your characters’ respective names are Manny, Moe, and Jack.

DM: I didn’t even know what I was doing. Somebody asked if I was in Magic Kid II, and I didn’t have a clue what Magic Kid II was. And I told people for years, “No, I wasn’t in that. I don’t even know what that is!” I finally figured it out: It was this afternoon—or whatever it was—that we spent with Stephen Furst on the movie he was directing. You know, it really wasn’t all that long after St. Elsewhere, and we were all happy to help Stephen with his directing and to get together.

One of the things that happened there was that we had this poker game we were shooting, and all of us from St. Elsewhere were sitting around the table, and we started talking about the show. As amazing as St. Elsewhere was—and it really was one of the great shows on television, and the writers of that show deserve a lot of credit for that—those writers and producers were bastards. And I thought I was the only one who suffered for six years on that show. It was not a happy experience, and I had always just kept that private. Well, it turns out that, as we were sitting around that poker table in Magic Kid II, we all started sharing our stories, and we all thought we were the only ones who were suffering on that show. And we all started sharing our stories of pain from doing it, and it was sort of cathartic, actually, to have that experience. So I’m kind of grateful to Stephen for bringing us together, so we could all have our little catharsis and share our stories.

The Slaughter Rule (2002)—“Gideon Ferguson”

AVC: Is there a favorite project you’ve worked on over the years that didn’t get the love you thought it deserved?

DM: Well, there’s probably a lot of them. Even though they got love from the people who saw them, it’s just that they didn’t get a wider experience of love. It’s hard to single out one, but there’s a movie called The Slaughter Rule that I did with Ryan Gosling when he was 19, by Alex and Andrew Smith. I was at Sundance one year, and I heard there were these two young filmmakers who wanted to talk to me about a movie they had. And I met Alex and Andrew, they brought me the script to The Slaughter Rule and I read it, and I loved it. I really loved it. And they asked if I’d do the role, and I said, “I’d love to do it.”

I think it took them three years, maybe four years, to do it from when they asked me. Originally they couldn’t get it done with me doing that role—there were two starring roles—and they were very heartbroken that they were going to have to ask other people, like Nick Nolte or other stars. But I said I understood that they had to get their movie made. So they went to other people, and those people, for whatever reasons, wound up not doing it, and eventually they came back to me, which I think they were happy they were able to do, because I was who they originally wanted. And they eventually actually got their money together.

At the time, Ryan had only done Remember The Titans, I think. He’d been a Mouseketeer with Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, and Christina Aguilera, and he really did not want to go down the Mouseketeer road. He’s one of the smartest people I’ve met. I auditioned with a number of young actors in Los Angeles with Alex and Andrew—some of them are now famous—and I’d go off-script and try to challenge them or whatever, and I sort of pushed him in these scenes. Ryan was really the one who could stand toe to toe with me when we did these scenes, and after we saw him, it really felt like there was nobody else who should do the role.

And he was offered another movie at the same time, which was a traditional Hollywood movie, and he was offered a bunch of money considering how inexperienced he was. But he really felt as an actor that he could go make the money, but it wasn’t the same quality of role as The Slaughter Rule, and he just felt like the best thing for him as an actor was to not take the money and to do the role that was really going to challenge him more. I absolutely loved doing this movie with him. He really had a quality—and now you can see it—that was shared by the best people I’d worked with and known, like Sean [Penn] and Jack Nicholson. He had that same quality as a young actor, and I felt lucky to have been a part of his experience as an actor and lucky that we all got to do it together. I’m just sorry more people didn’t get to see it.

Concussion (2015)—“Mike Webster”

True Detective (2015)—“Eliot Bezzerides”

DM: You know, I was a big fan—like most people I know—of that first season of True Detective, and when that came up, I’d just done Concussion out in Pittsburgh, and I’d been asked to do Outsiders, so I knew that was coming up, and there wasn’t a lot of time between the two to do anything else. But I was asked to do True Detective, and I was told that it would be… I don’t know, three episodes out of the seven? Something like that. And I’d be Rachel [McAdams’] father. It’s so incredibly top secret, this thing. Now there’s a number of things that do this, but the scenes, I was the only one allowed to see them. Agents couldn’t read the scripts, nobody could read the scripts, I wasn’t allowed to know anything about the story. I just knew it was for her father, and I could read this scene that was, like, written in lemon juice on parchment, so it would disappear as soon as you’d read it. [Laughs.] But I read the scene, and I thought, “You know, this is a really fun, kind of cool character, this isn’t something I’ve really gotten a chance to play, and they did an amazing series last year.” It was kind of like with David Simon: You have to go on faith and see what will come of it, because I don’t know anything about the other episodes, so I don’t know what’s coming, but it’s a chance to play a fun character on a potentially fabulous series.

So I did it. And I got to have really long hair, and I got to work with Rachel. Actually, the inspiration for the hair from Outsiders came from True Detective. When they were trying to figure out the look of the clan, there needed to be a look that, when we went into town, everybody immediately knew that we were Farrells, that we were of the Farrell clan. We needed to be identified. So I sent a picture to the producers of this hair from True Detective, and I said, “Look, if we just add stuff to the hair, bones or whatever, we can use it as the look on Outsiders.” And they all got really excited and wondered about how long it took to put on the wig and all that stuff, so that’s sort of the genesis for that. So I’m glad I did True Detective for a couple of reasons. [Laughs.]