David Oyelowo’s bravura performance anchors HBO’s unsettling drama Nightingale

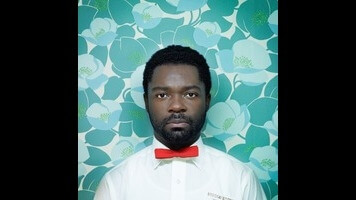

Social isolation feeds on itself, creating a relentless cycle that is remarkably difficult to break once it has begun. The fewer human connections a person makes, the less worthy he feels of making them, and his relationship to the outside world slowly deteriorates. The progression is a logical one, but that makes it no more conceivable for anyone who hasn’t experienced it. Hence, HBO’s unsettling psychological drama Nightingale isn’t a universally relatable film, even as it explores common emotions. David Oyelowo, fresh off his ballyhooed performance in Selma, is the film’s only star. His character, Peter Snowden, is the only face seen in Nightingale, his voice is only one of three heard, and Peter’s home is the only location. Peter’s abject loneliness makes the audience his only companion for the duration of Nightingale, and to watch his downward spiral is to be torn between equally powerful impulses to empathize and escape.

First-time screenwriter Frederick Mensch doesn’t elaborately define Peter or lay out his background in detail. The film only reveals that he lives in a ranch-style home filled with dainty, dated furnishings, and that immediately before Nightingale begins, he committed a heinous crime of passion, forcing him to tighten his grip on what’s most important to him. Peter isn’t invested in his work—he rings up groceries to keep busy—nor does he keep hobbies outside of documenting his humdrum life through a series of video diaries he broadcasts to an unspecified audience. Peter’s only focus, to put it euphemistically, is Edward, an estranged Army buddy with whom he made fast friends 18 years prior during the ride to basic training. All Peter wants to do is rekindle his relationship with Edward by cooking him the perfect gourmet meal, and Nightingale charts the acceleration of his psychosis as his desire to connect goes unrequited.

A single-character film rests squarely on the shoulders of the actor, and Oyelowo (who is also credited as an executive producer alongside Brad Pitt) turns in a breathtaking, visceral performance made more impressive by the strenuousness of the role. It’s certainly stagy, but that’s an unavoidable quality considering Nightingale is a story better attuned to the stage. In Oyelowo’s able hands, Peter isn’t a pure menace, and though he’s a limerent manchild with rage issues, it’s impossible not to feel for him. Peter spends the bulk of the film with a phone pressed against his ear, trying in vain to reach Edward as his wife Gloria runs interference. He can’t help but betray the depth of his neediness, even when he’s doing his best to play nice: “May I speak with Edward, please? I promise I won’t steal him from you. I just wanna… just want him for a moment.” Peter’s behavior eventually drifts toward stalker cliché, but Oyelowo still manages to keep him human.

Director Elliott Lester deserves equal credit for permitting the audience to empathize with Peter even though Nightingale introduces him immediately after he’s committed an indefensible, vicious act. Cinematographer Pieter Vermeer bathes Peter in gauzy light when Lester wants to show Peter in a stupor or state of alarm, literally softening him. Lester resists lurid angles on Peter’s crime, and forces the viewer to share Peter’s perspective. The audience never gets to see past Peter, to the point that when a newscast details his misdeeds, the camera doesn’t even scan over the television screen, it only captures Peter’s reaction. Lester’s directorial choices cut both ways. The narrow perspective creates the disconcerting intimacy on which Nightingale thrives, but Lester’s strict adherence to it often feels compensatory and makes the film come across more like a conceptual exercise than a story.

Still, the film is spellbinding and au courant, and not only because a character named Snowden is puncturing the privacy of one named Edward. Nightingale is also a decidedly yet subtly queer film. In a purely textual interpretation, Peter and Edward’s friendship is platonic, and the audience is left to guess exactly how one-sided the romantic feelings may have been. At no point in the film does Peter self-identify as a gay man, nor does the film place his relationship with Edward—whatever its parameters—within a larger context. But the circumstances around Peter’s crime suggest his same-sex longing, and an intercepted letter confirms that his sexuality has been an ongoing source of conflict within his religiously intolerant family. Mensch’s script wisely avoids putting too fine a point on the root cause of Peter’s mental imbalance, but it seems to lie at the intersection of his sexual identity and his military service. Soldiers exorcise battlefield traumas by ridding themselves of the memories, but that recovery process is fraught, if not impossible, when those memories are interwoven with the intoxication of first love.

Whatever the source of Peter’s instability, Nightingale goes slightly too far in absolving his actions, closing just after a treacly bit of dialogue in one of his video diaries. Peter’s parting sentiments are maudlin but his delivery is sober. His composed side is the one he allows his “audience” to see. The actual audience knows that the more histrionic Peter’s behavior, the less he’s acting.