David Simon may be television’s most self-effacing brand-name storyteller, but he’s not immune to the joys of reverse prestige, reveling in his shows’ small, exclusive audiences. In interviews pegged to his HBO miniseries, Show Me A Hero, Simon has become fond of talking about how no one will watch the show, which depicts the harrowing true story of a brass-knuckled fight over public housing in Yonkers, New York. Simon’s work has never been widely consumed (not even The Wire), a natural consequence of his devotion to telling stories about municipal conundrums, systemic breakdowns, and the residents living alongside roads paved with good intentions. But he might be disappointed by the warm response to Hero, which could become his most popular series so far. It’s not only his most concise and accessible work yet, it’s also the most timely—a neat trick for a period piece set in 1987.

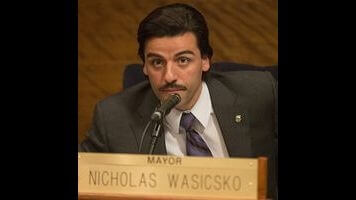

Simon reteamed with his former Baltimore Sun colleague William F. Zorzi to adapt Hero from the non-fiction book by Lisa Belkin, which chronicles the racially charged conflict around a plan to build 200 units of affordable public housing in the relatively tony east side of Yonkers. Human beings need safe, comfortable homes to live in. It sounds simple enough, at least to Nick Wasicsko (an Emmy-worthy Oscar Isaac), who at 28 has just become the country’s youngest mayor. “The thing is, people just want a home, right? It’s the same for everybody,” he says, in one of his many displays of willful naivete. But Wasicsko cruised to victory on the support of the middle-class and mostly white residents of west Yonkers, who were fighting tooth-and-nail to block the poor and mostly black residents of a infernal, east-side housing project from moving into their neighborhood. They rightfully expected an ally in Wasicsko, and got just the opposite.

Wasicsko quickly learns the folly of campaign pandering when a state judge makes good on his promise to levy a million dollars in fines against the city of Yonkers for every day Wasicsko can’t convince his intractable city councilmen to approve a housing resolution. Faced with the prospect of near-immediate insolvency, cooler heads prevail, and the leaders of Yonkers agree to build the housing, to the consternation of many of their constituents. The townhomes are built, the residents move in, and the community begins the process of learning how to live together. The post-resolution phase is where Hero becomes a gripping saga of what poet Robert Burns called “man’s inhumanity to man.”

Public-housing regulations are complex and dreadfully boring, even by Simon’s television-as-civic-lesson standards. But much as he did in The Corner, The Wire, and Treme, Simon digs human stories out from under the avalanche of legal briefs. Despite being a scripted television show, Hero makes a passionate case for the vitality of careful, dogged journalism at a time when the public’s faith in the discipline has waned considerably. Simon and Zorzi didn’t settle for an as-is adaptation of Belkin’s meticulously reported book, first released in 2000. Zorzi returned to Yonkers and tracked down the characters depicted in the book, proof of his dedication to accurate and properly nuanced storytelling.

A battle like the one waged in Hero is, after all, about nuances. It’s about small but heartbreaking moments, like when Norma (LaTanya Richardson Jackson), a former home nurse aide forced into early retirement by diabetes complications, sits with her son waiting in vain for a nurse aide of her own to show up. He tries to convince her someone will be brave enough to stroll into their urban war zone to take care of her, but she knows better. “Son, no one’s coming,” Norma says, as if she never believed it to begin with. There are real people on the other side of the issue too, people like Mary Dorman (Catherine Keener) who elevate pretzel logic to an art form as they explain why their opposition to the housing—so fierce that someone planted a pipe bomb once construction began—is anything but racism. Hero’s issues and themes are even thornier than those tackled by The Wire, and it doesn’t provide the audience the comforting cop show framework to process them. Between its unsettling subject matter and celebration of shades of gray, it’s almost as if Paul Haggis, who directed all six episodes, is doing penance for the broad, bludgeoning Crash.

Hero serves as a reminder of how little progress the country has made toward racial harmony. It isn’t always easy to watch, but it’s always compelling, and almost unfairly stocked with stellar performances. It’s also sadly still relevant. When the furious white citizens of Yonkers voice their concerns at a town hall meeting, the sentiments are startlingly similar to those heard in a recent This American Life piece on school integration in Missouri. Much like that piece, Hero manages to avoid cynicism simply by focusing intently on the humanity beneath the rhetoric.