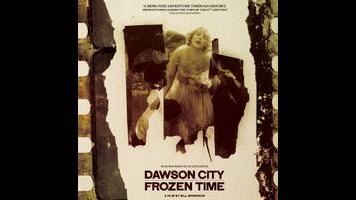

Dawson City: Frozen Time unearths history in 500 reels of rotting film

Anyone who has tried writing about history can tell you that the hardest part is knowing where to stop. This is the problem with Bill Morrison’s intelligent but at times exhausting avant-garde documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time; at two hours, it’s just too long and deliberate for its own good. There comes a point when even the attention span of the niche audience that exists for a narration-less documentary about silent film begins to lag behind Morrison’s own interest in archival and historical minutiae.

But this isn’t a boring subject. In 1978, a Pentecostal minister and part-time backhoe operator in the small and far-flung Canadian town of Dawson City discovered a stockpile of 500 nitrate film reels, dating mostly to the mid to late 1910s, buried behind the local gambling hall, Diamond Tooth Gerties—a case of the past being literally unearthed. An archive can become a skeleton key to the doors of the past, and the trove of poignantly degraded silent films discovered in Dawson City provides Frozen Time with an entry into a variety of subjects: Dawson City’s heyday as the center of the Klondike Gold Rush; its ties to the fortunes of Sid Grauman (of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre fame) and the Trump family, whose first hotel was an inn and brothel in the Yukon that served prospectors bound for Dawson City; the extreme destructive potential of nitrate film stock, which was eventually replaced by cellulose acetate for safety reasons; the forced displacement of indigenous communities in Canada; and even the role Dawson City played in the history of nonfiction film, as the subject of the 1957 documentary City Of Gold (viewable on YouTube, courtesy of the National Film Board Of Canada), which popularized the now-ubiquitous technique of panning and zooming across archival photos.

Morrison, who is best known for Decasia, an experimental feature artfully cut together from distorted and decayed nitrate footage, conveys these bits of history through dry little captions superimposed over black-and-white photos and silent footage; aside from some interview excerpts at the very beginning and end of the film, the soundtrack consists of nothing but muffled sound effects and ambient music composed by Alex Somers. Thus, Frozen Time puts itself in an odd spot. Its scope and subject matter aren’t very different from those of any number of popular works of nonfiction that use an esoteric point of departure to get into the currents of an era. But it’s much more involving as a work of pure and hypnotic collage than as a researched narrative of facts, dates, and names. Because of its remoteness, Dawson City was a final destination for film distributors in the silent era, not worth the trouble of return postage. Although Morrison found at least one historically significant film in the process of making Frozen Time—namely, some one-of-a-kind footage of the notorious 1919 World Series—it’s in forgotten newsreels, serials, and features that he finds the spirit of a lost era, given a frail and somehow human quality by the tumors and barnacles of severe nitrate decay that riddle the sharp but intentionally unrestored footage. One montage deftly cuts together scenes of characters melodramatically reacting to newspaper headlines in different movies that were found buried in Dawson City, turning a forgotten cliché into an insight. Frozen Time is at its best in moments like this, when it uses Morrison’s obsessive interest in cinematic detritus to express rather than inform.