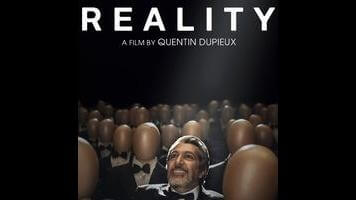

Daydreams become nightmares in Quentin Dupieux’s Reality

In Reality, the latest meta-whatsit from musician-turned-filmmaker Quentin Dupieux (Rubber, Wrong), a cooking show cameraman (Alain Chabat) is given the chance to direct a sci-fi horror movie, provided he can bring the producer a genuine scream of agony in 48 hours. There’s a pinch of satire there, but only for flavoring; Dupieux, who records as Mr. Oizo, is mostly interested in constructing sequences and loops.

The cameraman calls himself from a dream, or he is being dreamt by someone, or he is a character in a movie within a movie within this movie, directed by an ex-documentary filmmaker named Zog. The producer—who is named Bob Marshall (Jonathan Lambert), but doesn’t speak English—keeps offering cigars or cigarettes and moving the conversation between his desk and the balcony, where he keeps a sniper rifle to shoot surfers. Sometimes, his desk is in the woods.

Maybe it has something to do with the little girl who found a blue videotape in the belly of a wild hog shot by her father—or maybe it was the cameraman that her father shot, in the leg, in her dream. Or maybe it’s all in the head of the cooking show host (Jon Heder), who wears a rat suit and thinks he has eczema, but doesn’t. Sometimes, it’s his dermatologist—who really does have eczema—that hosts the cooking show.

Scenes—some of them very funny, some tedious—coil into one another. People wake up from dreams within dreams. It’s nothing deep—just an absurdist riff on the way the creative interior life can start collapsing in on itself under the weight of performance anxiety, and how daydreams can turn into nightmares when they become practical, which is to say, when they becomes realities and you have to go out and make them.

Dupieux—who writes, shoots, edits, and scores his own films—seems to know a thing or two about this. Reality is a comedy about perfectionism, built around imperfect repetitions, as though it were constantly being re-drafted. The place is Los Angeles, the Paris-born Dupieux’s adopted hometown—the dream factory, taken at face value. It’s a personal and unreal L.A., seen through the filmmaker’s signature acid-washed color palette of sky blue and off-beige. People drive oddball cars: Army Jeeps, identical early ’80s Toyota Supras, 50 Series Land Cruisers. Almost everyone speaks French.

In other words, this is Dupieux’s personal headspace of electronic beats, funky obsolete technologies from the wood-panel era, and nondescript L.A. street corners, seen as comically unreal through the eyes of a foreigner. A viewer can’t help but take it as an artistic statement, even though nothing—not even the nods to Mulholland Dr.—suggests that Dupieux’s motivated by anything more than a hankering to make something weird and funny. He succeeds on the first part, and fitfully accomplishes the second.