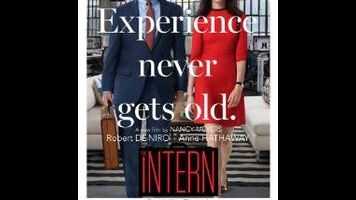

De Niro and Hathaway charm their way through Nancy Meyers’ The Intern

What might have once seemed like heresy now feels like an inevitability: Given Robert De Niro’s late-career embrace of big-studio comedies and dramedies, sooner or later he had to find himself in a Nancy Meyers film. Over the course of her successful Hollywood career, Meyers has endeavored to hire name actors of a certain age, having given late-career hits to Jack Nicholson, Diane Keaton, and Meryl Streep; hers is a filmography where Steve Martin, Alec Baldwin, and Mel Gibson count as relatively young bucks.

Even with plenty of Focker experience, De Niro doesn’t seem like a great fit for the copper-pot, white-sweater aesthetic favored by movies like Something’s Gotta Give or It’s Complicated. But in The Intern (somehow not titled You Know How It Goes) Meyers taps into De Niro’s sometimes underappreciated talent for conveying warmth. Ben Whittaker, the retiree De Niro plays, doesn’t exist to administer grumbly dressing-downs and grimaces to young people; he responds to an ad for a senior intern program in all earnestness, looking for something to occupy his time as a lonely but still energetic widower. Interning at About The Fit, a burgeoning ecommerce start-up run by thirtysomething Jules Ostin (Anne Hathaway), beats the workaday boredom of retirement—a sentiment that presumably applies to actors signing up for a Nancy Meyers comedy, too.

“Comedy” may not be the right word. Though Jules is initially disinterested in her company’s intern program, the movie doesn’t place her and Ben at comical odds. She ignores him, he begins to learn the ropes at a company with no walls and lots of email, and she takes notice of his unflagging loyalty. Soon he’s serving as Jules’ driver and sometime confidante as she receives pressure to hire a more experienced CEO to run the company she founded. Thankfully, their closeness never turns into a May-December flirtation. After a sometimes-grueling series of romances, Meyers has made a movie about male-female friendship—about two people who come to really like each other. Jules admires Ben’s old-fashioned work ethic and positive attitude; Ben admires Jules for her toughness and business sense; and Meyers, it seems, really digs both of them, and with far less toxic self-regard than some of her other films. The obligatory scene where she writes dialogue complimenting her own writing comes early and just once, when an About The Fit employee mentions that Ben’s application video—the narration of which Meyers has just used to open the movie—made some people cry.

Meyers also limits her usual conspicuous displays of wealth, at least as much as she can. Hard-charging Jules and mild-mannered Ben both live in well-appointed two-story homes, with beds covered in throw pillows, because Meyers cannot conceive of a world where a successful person might not buy dozens of throw pillows. But the ostentatiousness is confined slightly by the movie’s Brooklyn setting (still: watch out, Brooklyn; you just became Nancy Meyers territory), and more so by its leads. In the past, Hathaway has appeared overly studied in her glossy comedies, but here, juggling her job, husband, and young daughter, she gives a more relaxed performance, even when playing high-strung. (She nearly sells the notion that a thirtysomething woman would wistfully pine for the days of real men like Jack Nicholson and Harrison Ford—in other words, nearly makes Nancy Meyers’ tastes sound like her own.) De Niro, too, slips into his role with ease. He sometimes looks at her like an admiring father might, but never tips into condescending lecturing.

Their relationship is very sweet, but it’s not very funny. It’s also not, save for a few dilemmas that pop up in the final stretch, particularly dramatic or compelling, beyond the smiles of its magnetic leads: De Niro’s, small and crinkly, and Hathaway’s, wider and flanked by parenthetical dimples. They make good company, and for much of its running time, The Intern proceeds through a series of extended pleasantries. Ben helps Jules; Jules appreciates Ben; Ben helps some likable goofballs (Adam DeVine, Zack Pearlman, Jason Orley) at the office, and they engage in the movie’s single instance of comic shenanigans: the mildest, slightest possible style parody of the Ocean’s movies as they bumble through the retrieval of a mis-addressed email.

The lack of comic goals allows Meyers to write and write; a key emotional scene between De Niro and Hathaway late in the movie rambles on like a first draft, and the movie swells to the two-hour mark. This kind of unhurried, low-conflict story coming from a mainstream filmmaker might be more invigorating if not for the eventually wearying idealization of the De Niro character and the odd implications that come along with it. Absent an object of romance, the usual Nancy Meyers fantasizing creates an employee who lives only for his job, comes to treat his co-workers (and no one else!) as family, and does it all for no money, indefinitely. De Niro and Hathaway, then, reveal themselves as almost dangerously charming. They nearly disguise that Meyers, while trying to make a feminist movie about friendship, has cheerily advocated for the enslavement of the elderly.