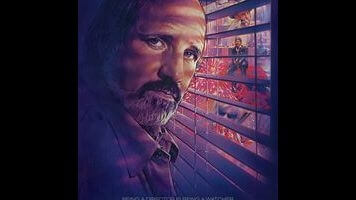

At the very least, De Palma comes much closer to capturing the long-form-interview spirit of Hitchcock/Truffaut (1966) than last year’s official documentary on the book did. De Palma, like his idol, submits to a complete survey of his filmography, discussing each movie at length and in chronological order, from the shoestring black comedies of his salad days all the way through to the gonzo power games of his recent Passion (whose title works as a neat summary of this project and the career it chronicles). De Palma is just De Palma gabbing for two hours into a camera, and that’s its ultimate limitation, but also its great strength. The director’s candid, reflective, and funny—a dream interview subject, imparting hard-won wisdom and telling juicy behind-the-scenes stories. At times, the movie almost functions like a makeshift film-school seminar, albeit one whose professor has assigned his own textbook: De Palma explains (and De Palma illustrates) the merits of the split diopter shot, while championing long takes as a tool for sustaining emotional beats and CGI as an enemy to craftsmanship.

Fans, of course, will gobble up the anecdotes. Obsession (1976) proves an especially fruitful source of those, as De Palma hilariously recalls pissing off composer Bernard Herrmann (an early link straight to Hitchcock) and makes no bones about Cliff Robertson nearly sinking the film. The earliest chapters of De Palma’s career arguably supply the greatest fascination, in part because they dual-function as an intimate origin story of his whole bound-for-glory entourage, the film-geek heavyweights who would soon reshape Hollywood. There’s a babyfaced Robert De Niro, already showing glimmers of the fierce talent he’d unleash only a few years later; there’s an adorably collegiate Steven Spielberg, filming from the front seat of a car. De Palma recognizes its subject as one part of a larger movement, while also acknowledging that his sensibilities—unsentimental, blackly comic, sometimes vulgar—made him the outlier in a group of more commercial-minded compatriots. De Palma, meanwhile, expresses a keen self-awareness about his own habits, failures, and voyeuristic impulses. (He sounds out-of-touch exactly once, while discussing his distaste for the way Scarface has been embraced by hip-hop culture.)

Is it even worth mentioning the name directors coaxing all this conversational gold out of the filmmaker? De Palma has been helmed by none other than Noah Baumbach (Frances Ha, Greenberg) and Jake Paltrow (Young Ones), though you’d never guess as much from the strictly utilitarian, talking-head strategy they adopt here; never once do they even speak from the other side of the lens. There’s a certain irony in a filmmaker this stylish, this obsessed with form, receiving his lionization in a documentary so functionally assembled. Then again, maybe De Palma and his madly, garishly inventive thrillers provide all the personality De Palma needs. Watching a sequential rundown of his greatest hits, all accompanied by some especially lively director’s commentary, it’s easy to imagine De Palma’s shadow engulfing a generation of imitators, the same way Hitchcock’s engulfed him. Will the glorious split-screen climax of Carrie one day serve as its own entryway into a different filmmaker’s oeuvre?

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.