Debut feature The Mend is delectable, if familiar

Part of the fun of watching a new filmmaker develop his or her own voice involves noting early influences, then seeing them get integrated into a unique personal style. Rian Johnson’s feature debut, Brick, was a superb Coen brothers pastiche; by the time he made Looper, seven years later, he’d come into his own. It took Paul Thomas Anderson a while to fuse his love for Scorsese and Altman into something that’s now unmistakably PTA. So here’s an opportunity to get in on the ground floor with a talented fellow named John Magary, whose first film, The Mend, plays like an American take on the work of French filmmaker Arnaud Desplechin (Kings And Queen, A Christmas Tale). Desplechin’s pictures can be as maddening as they are exhilarating, and the same is true of The Mend, which sometimes seems in danger of over dosing on its own stylistic flourishes. Nonetheless, it’s a hugely promising introduction to a director who’s just getting started.

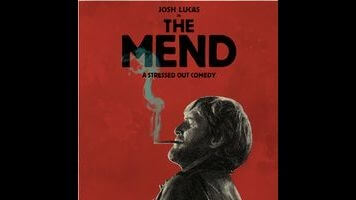

Like the aforementioned Desplechin films—best described as “sprawling”—The Mend is difficult to summarize. Indeed, it takes a while even to work out which characters are central, as the movie’s first half-hour is devoted entirely to a New York house party, with Magary’s camera lightly glancing across everyone who’s stuffed into the small apartment, eavesdropping on random conversations, demonstrating little to no favoritism. The presence of Josh Lucas, who’s more famous than anyone else in the cast, is a big hint, though, and eventually it becomes clear that the story, such as it is, concerns two brothers, Mat (Lucas) and Alan (Stephen Plunkett), who have little in common apart from trouble with the women in their lives. Mat has just been tossed out of the place he shares with single mom Andrea (Lucy Owen), and shows up at Alan’s apartment during the party, uninvited, to crash. Alan and his live-in girlfriend, Farrah (Mickey Sumner), then depart for a vacation in Canada, unaware that Mat is still passed out in a spare room. When Alan returns home early—and alone—this already strained fraternal relationship gets tested further.

That’s not much of a narrative, but it’s the idiosyncratic details and chaotic rhythms that distinguish The Mend from the bland personal melodramas that populate Sundance. (Magary premiered the film at SXSW last year.) Right from the start, there’s a jagged vitality at work: A scene of Andrea arriving home to find Mat playing hide and seek with her young son (Cory Nichols) abruptly cuts to Andrea and Mat having sex, then cuts again seconds later to Andrea screaming at Mat to get the fuck out, with no indication of what happened. What follows is similarly disorienting and arresting—a maelstrom of strong emotions and offbeat episodes, peppered with pungent dialogue (“Your voice! Someone should bottle it up and throw it at terrorists.”) and stubbornly resistant to conventional catharsis. Lucas and Plunkett aren’t terribly convincing as brothers, but they’re well matched all the same. Alan, in particular, deepens over the course of the film, revealing a wounded soul beneath the exterior of an over analytical tightass. Lucas occasionally overdoes Mat’s dissolute fuck-up routine, but he’s more present and engaged here than usual. And this is the rare male-driven movie that does right by its female characters, who are equally complex and thorny.

The Desplechin influence has its pluses and minuses. Magary throws in some iris effects that don’t serve much purpose, and one scene, in which Alan visits an elderly friend of the family (Austin Pendleton) at the request of his mom, seems too directly indebted to the monkey-behind-the-radiator bit (don’t ask) in the French filmmaker’s My Sex Life… Or How I Got Into An Argument. On the flip side, The Mend’s secondhand whirligig approach provides terrific nervous energy, and its prominent use of a string-based score—atypical for this kind of indie production—lends the film a weight that makes it seem quasi-European. One of the knocks on Desplechin’s movies is that they’re too all over the place to cohere, and this one, likewise, is more memorable for its individual parts than it is for their sum. When Mat and Alan steal the walkie-talkie of a movie set’s P.A. and use it to taunt the crew, however, or when Andrea’s son says goodbye to the brothers and is crestfallen to receive a casually indifferent reply, the absence of a big picture doesn’t feel that important. Plus, Magary’s got time (hopefully) to develop a stronger sense of purpose. In the meantime, he’s made something delectably derivative, which is what up-and-comers are supposed to do.