In The Deer King, Studio Ghibli alumni play it too safe

A beautiful-looking movie about a mystical plague comes up short despite its timely themes

Maybe we’d be less blasé about a global pandemic if it arrived in a creeping purple cloud, full of wolves with glowing eyes. Such is the method of the “mittsual,” a plague descending on the nations of Zol and Aquafaese, former adversaries who brokered a tenuous arrangement, in the The Deer King. The film is based on Nahoko Uehashi’s two-volume Japanese fantasy novel, published in 2014. Like many anime storytellers before him, Uehashi uses fiction to explore historical dynamics without directly offending contemporary partisans—or otherwise jeopardizing the movie adaptation’s international box office potential.

The Deer King marks the feature directorial debut of Studio Ghibli veterans Masashi Ando and Masayuki Miyaji. Between the two of them, they’ve worked on some of the most acclaimed and popular anime movies and TV shows, from Pokemon and Attack On Titan to Spirited Away, Your Name, The Tale Of Princess Kaguya, and Paprika. That’s probably an unfair amount of hype to put on them for this project, especially since The Deer King evokes a number of a classic Ghibli movies, and as an overall viewing experience it’s … fine. Aggressively, middle-of-the-road fine. The risk-taking of someone like Satoshi Kon is nowhere to be found; instead, the film exudes a concerted effort to be safe and crowd-pleasing, which ironically leads to more of the former than the latter.

Specifically, it feels a lot like a Princess Mononoke knock-off, complete with a climactic moment involving a girl riding a wolf and leading the pack, albeit to different effect. Though the recipe of a feudal setting with fantasy and myth-making elements ought to be strong, the mixture is off, like a handsomely plated sandwich where the ingredients are more bland than anticipated.

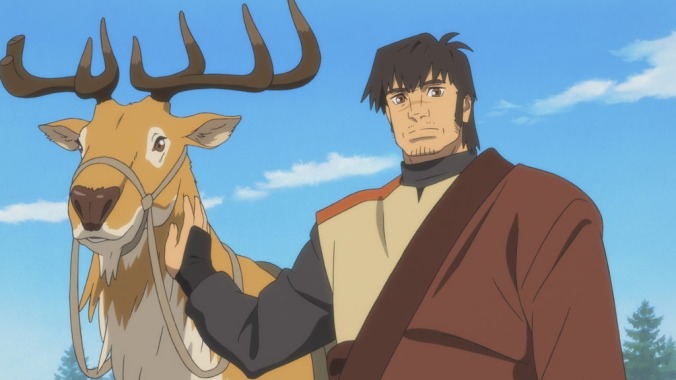

The Deer King’s main protagonist, Van, enters the story theatrically, even biblically: first staying a slaver’s whipping hand to protect a vulnerable fellow slave, then adopting that slave’s extra burden, he graduates to a Samson-style breaking of chains to save a baby girl from a plague dog. In the process, he sustains a wolf bite which gives him super powers to change the physical structure of the wooden bars keeping him confined. Taking the girl, Yuna, as his own adopted daughter, Van retreats to the mountains, where he lives among country dwellers, using his super-instincts to tame “pyuika,” the wild deer who live among the Aquafaese.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.