Admirable without actually being very good, Demetri Martin’s debut as a writer-director, Dean, makes a smart decision right from the outset. At its heart, this is a movie about the grieving process, which seems like inherently depressing subject matter. Martin opts instead to play it primarily as light comedy, focusing on two men who’ve suffered the same loss but aren’t conscious of how much it still affects them. The film’s poignant aspects emerge gradually, coming to the fore only toward the end; but it’s not as if they arrive out of nowhere, since the death in question is noted in early voice-over narration and comes up frequently thereafter. Dean turns out to be quite touching, in retrospect. If only it were funny, clever, or in any other way particularly inspired from moment to moment.

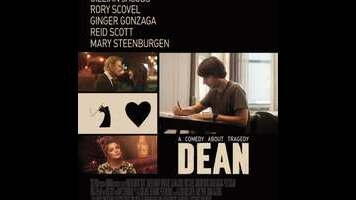

Loosely inspired by the death of Martin’s father, whose name was in fact Dean (but not that Dean Martin), the film begins about a year after Dean’s mother dies. Dean (Martin—damn, this gets confusing), an artist who improbably seems to make a living solely from books of his simple line drawings, has been coping reasonably well, in his own opinion, but freaks out a bit when his father, Robert (Kevin Kline), announces his intention of selling the family home and moving to a smaller place. In an effort to postpone his own part in that process, Dean flees New York for Los Angeles, where he falls for an acerbic woman named Nicky (Gillian Jacobs) and aggressively pursues a serious relationship with her, oblivious to his true reason for needing it. Meanwhile, back in New York, Robert starts dating his real-estate broker (Mary Steenburgen), only to discover that he’s perhaps not quite as ready to move on as he’d thought.

On paper, the idea of a father and son trying and failing to fill the hole that Mom’s absence has left in their lives is a solid one. Dean’s dual romances, however, are too bland to serve even as temporarily credible distractions, much less as something the viewer might enjoy. Kline and Steenburgen (who previously co-starred in Life As A House, albeit not as a couple) strike nicely tentative notes together, but Martin doesn’t give them enough screen time to achieve real catharsis. The emphasis is squarely on Dean and Nicky, whose banter never gets remotely sharp enough to crackle—it’s mostly just Dean being slightly awkward and Nicky conveniently finding that charming. And when Nicky isn’t around, we’re left with Dean’s L.A. friend Eric (Rory Scovel), who’s apparently hilarious because he loves his cat. Somehow, that’s the joke.

Dean’s biggest problem, frankly, is Martin’s decision to play the title role himself. The deliberately flat affect he employs works well in his stand-up routines, putting ironic spin on jokes so dry that they might not land were they delivered with, say, Jerry Seinfeld’s trademark rising intonation. But that approach can create a vacuum when applied to a traditional character. Taking Woodstock is one of Ang Lee’s weakest films in large part because of Martin’s fatally recessive, utterly forgettable performance as its lead. He’s a tad more energetic here, but never really makes Dean much more than a generic insecure wiseacre—someone who’d usually be the hero’s buddy, with half a dozen lines. Sporting a Beatles haircut at age 44 is the most distinctive thing about the guy. When the movie finally shifts into catharsis mode, Kline conveys a man belatedly realizing how empty he feels. Martin, on the other hand, just looks kinda bummed.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.