Demolition does a rush job rehabbing American Beauty

Jean-Marc Vallée’s Demolition attempts to update American Beauty’s precarious mix of satire and wish fulfillment for the post-Recession era, complete with quirky voice-over, fantasy sequences, a soundtrack of generational-nostalgia signifiers and classic rock, and a WASP protagonist who shows his disaffection with privilege by applying for a working-class job and befriending gay men and surly teenagers, here merged into a single character. It even has Chris Cooper as an overbearing dad with a secret. But despite a few electric moments, the movie never makes anything of its stylized displays of frustration, ending in a whiff of narrative and emotional cop-outs. Say what you will about American Beauty, but at least it had a climax.

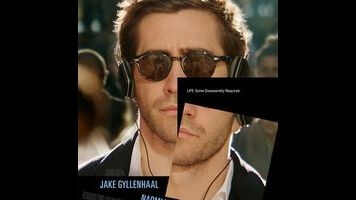

Jake Gyllenhaal stars as Davis Mitchell, Wall Street broker and proud owner of an honest-to-God glass house. (Not to put too fine a point on it, but Demolition is not a subtle film.) When his wife is killed in a car accident, Davis is at a loss for what to do, unexpectedly returning to work, engaging in familiar rituals of alienation involving TVs and headphones (as American Beauty’s Lester Burnham had The Who, Davis has My Morning Jacket and early Sufjan Stevens), and taking to such symbolic pursuits as disassembling appliances and writing long, highly personal complaint letters about the vending machine that ate his $1.25 in the hospital waiting room. Said complaint letters lead him to connect with vending machine customer service rep Karen (Naomi Watts) and, eventually, her glam-rock-obsessed son, Chris (Judah Lewis), both in the midst of their own crises of identity.

Demolition’s opening stretch avoids settling into a groove, playing out as a series of left turns that yield uncomfortable laughs and pinpricks of insight, with Davis’ observation that “for some reason, everything has become a metaphor” being both a self-aware jab and a concise definition of how grief feels. But though Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club, Wild) has a very fine sense for performance, and gets the cast in tune with the broadly drawn, seriocomic tone, his inclination to let actors set the frame is often at odds with Bryan Sipe’s artificial and deliberately contrived screenplay. Here, the line of subversive transgression is violence rather than desire; Sipe’s writing flirts with the edge of fascism, as anything full of daydream sequences about guns and complaints about how everything is ugly is wont to do.

Disdained by his father-in-law-slash-boss (Cooper)—who suggests that “If you want to fix something, you have to take it apart”—Davis begins to deconstruct his life in order to build a new one; unfortunately, he’s a lot more interesting as a caustic, disassociated observer than as the do-gooder he’s supposed to become in time for the complete shambles that Demolition tries to pass off as an ending. Having spent so much time and energy taking apart Davis’ materialism and sense of emptiness—and having traded his toolbox for a bulldozer, both figuratively and very, very literally—the movie can’t seem to figure out how to make heads or tails of the pieces or how they could fit into a moment of catharsis. It pastes together whatever it can with insincere goop, still wet and sticky as the credits roll.