Denial is pretty dull for a film with so much chilling relevance

Denial tells a fact-based story that should be a footnote, but holds a disturbing degree of present-day resonance. In 1996, self-styled historian David Irving filed a lawsuit against actual historian Deborah Lipstadt and her publisher for references in her book Denying The Holocaust that Irving considered libelous and that Lipstadt considered true. She went forward with the trial, even though it was held in Irving’s native England, where the burden of proof is placed on libel defendants, not their accusers. The story positively buzzes with present-day parallels, from its invocations of elaborate, grandstanding conspiracy theories, to the way deniers bend history to better suit their prejudices, to the way Irving seems to consider being called a Holocaust denier more offensive than denying the Holocaust. Intentionally or not, Denial is perfectly timed to a season of insane conspiracy theories and feelings-based readings of facts.

It’s disappointing to report, then, that as an actual procedural narrative, the film is only passably interesting, afflicted with the kind of stop-start rhythms endemic in movies that compress a legal battle spanning years into a two-hour movie. The lack of momentum doesn’t always come from the time skips. Denial sometimes nobly trips over its own purported accuracy, as in a sequence that explains how all of the major characters except Lipstadt will hear the verdict before she does, then proceeds to watch everyone else not react to the verdict they already know before it is read in court.

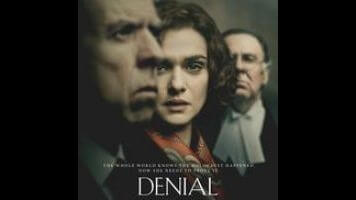

Rachel Weisz gives the red-haired, Queens-accented Lipstadt a distinctive moxie; she bristles when her solicitor Anthony Julius (Andrew Scott, best-known as Moriarty from TV’s Sherlock, amusingly buttoned up here) and barrister Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson) treat her more as a client than a fellow litigator. Beyond the public conflict pitting a Holocaust denier against the accepted historical record, there are quarrels within the defense (mainly coming from Lipstadt) about how to approach the argument. Lipstadt wants to take the stand herself and bring in Holocaust survivors to testify with their memories. Julius believes that they should not be subjected to Irving, serving as his own lawyer, or the way he may attempt to exploit their imperfect memories and plant seeds of doubt. Rampton, meanwhile, irritates Lipstadt by asking questions that uncomfortably mimic the thought process that asks for “proof” of gas chambers at Auschwitz 50 years after the fact.

These are interesting conflicts, but perhaps not quite enough to fill out a feature film—at least not the way it’s assembled by screenwriter David Hare and director Mick Jackson. Hare is a playwright, but doesn’t seem to have brought his A game to lines like, “You think they want to testify for themselves? It’s not for themselves they want to testify.” Jackson, an English journeyman with a surprisingly diverse set of Los Angeles portraits on his filmography (L.A. Story, The Bodyguard, Volcano), has done primarily television work since the late ’90s, and it shows: Denial is as tasteful, informative, and devoid of visual spark as a mid-level TV movie.

It does boast a memorable villain, of sorts, in the form of Irving, played by veteran character actor Timothy Spall as the picture of self-impressed conviction, who has a ridiculous answer for every charge against his work. Spall is first glimpsed glowering in the shadows, but one of the most terrifying scenes in the movie places him out in the open. It simply shows Irving doting on his very young daughter, with the chilling corollary, revealed much later, that he has made up a racist and anti-Semitic ditty to sing to her (noting, of course, that she is too young to understand it, rendering it therefore harmless). With Irving’s casually poisonous, endlessly self-justified attitudes on display, it’s easy to understand Lipstadt’s fight against his desire to “[make] it respectable to say there are two points of view” on this matter. It’s harder, though, to process Denial’s treatment of that fight as consistently gripping drama.