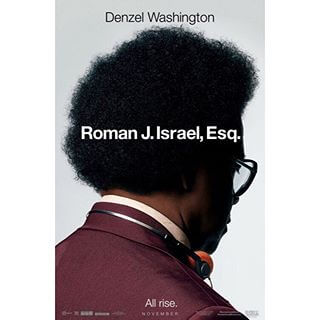

Roman has never had to worry much about appearances, which is one reason he dresses like he assembled his ensemble from a community-theater costume trunk. For decades, he’s been the silent partner, the hidden brains of the operation—toiling away behind the scenes of a struggling law firm, doing all the leg- and paperwork while his more presentable counterpart handled courtroom duties as the face of the company. Not that Roman could afford fancy duds even if they were a high priority: He’s always been the unglamorous paradigm of the selfless public servant, funneling energy and resources into pro bono work. (He even carries a literal symbol of his pie-in-the-sky idealism: a bulky briefcase containing an absurdly ambitious class-action lawsuit he’s been compiling since forever ago.) If Roman looks like he stepped straight out of the 1970s, it’s because he clings hard to that lost era of activism—a time when it still felt like fighting the fat cats was a battle that could be won.

Roman J. Israel, Esq. seems to have been yanked, too, from the 1970s. Not in its appearance, which is modern and sleek, thanks to the typically handsome lensing of Robert Elswitt, but certainly in its general shagginess. Gilroy, brother of Tony, made a splash a few years ago with his directorial debut, the magnetically diabolical Nightcrawler, which attempted to transport the it-bleeds-it-leads cynicism of Sidney Lumet’s Network to a new age of sensationalistic journalism. (If its insights were a little shopworn, its nocturnal nightmare energy sure wasn’t.) For his sophomore feature, Gilroy has turned to the hard-nosed integrity of Lumet’s legal dramas (particularly The Verdict), fashioning from their remnants another Los Angeles character study, this one almost an inverse of Nightcrawler: If that film followed an amoral antihero finding his true calling in an industry rotten enough for him to thrive, Roman J. Israel wants to show what happens when a truly virtuous person is slowly, inevitably corrupted by a dishonest profession.

The film begins with one of those hackneyed, moment-out-of-time teases, with Roman typing out a letter confessing to the breach of personal values he’s committed. It then rewinds the clock back to three weeks earlier, when the attorney with the heart of gold and the disposition of an ornery chess prodigy discovers that his professional partner has fallen into a coma and his agency is being dissolved. He quickly falls into the employ of wealthy, high-end lawyer George Pierce (Colin Farrell, serviceably slick and ambivalent), who admires Roman’s brain but has little use for his eccentricity and his habit of running a law firm like a charity. Will Roman be corrupted by this devil’s advocate, by the allure of money and clout and a real suit?

The answer is a resounding “sort of.” Nightcrawler pressed forward with fatalistic purpose, pushing Jake Gyllenhaal’s bug-eyed, entrepreneurial buzzard to a place that was no less disturbing for how easy it was to anticipate. What’s strange and frustrating about Roman J. Israel is that it doesn’t go anywhere radically surprising or interesting, but sure takes its time getting there; the film just kind of ambles, like a lousy imitation of the Nixon-era American character pieces it superficially imitates. How does an honest man abandon his hard-won, long-held scruples? The answer involves a murder case, the temptation of easy money, and a slippery ethical slope into compromise. But that element doesn’t emerge until deep into this overlong, digressive drama, and once it arrives, briefly giving Roman J. Israel at least the flavor of a thriller, the paranoia doesn’t take, however vaguely Roman’s rat-nest apartment—cluttered with stacks of old soul records and jars of peanut butter—recalls the home of Harry Caul. Gilroy also wastes real estate on an unbelievable, tentative romance between Roman and a young, pragmatic civil rights activist (Carmen Ejogo), who responds to his piss-poor social skills and kids-these-days sanctimony with little but swooning admiration.

Roman J. Israel, Esq. is almost offbeat enough to look admirable; like its namesake, it’s a peculiar anachronism, almost jarringly out of step with the way movies like this now move. (Those waiting on a big courtroom showdown will find they’ve stumbled into the wrong film.) But as a kind of moral thriller on the difficulty of holding onto your virtue—of not being lured away from the good cause by the promise of long-overdue recognition, clout, and compensation—the film is bogus, because it never keys us into Roman’s flirtation with the dark side. He just kind of drifts into a bad decision, his downfall more a product of plot demands than motivation. Maybe it’s that Gilroy, and Washington, never make us believe Roman as a character in the first place. He’s as phony as his inelegant name, and Roman J. Israel, Esq., in its languor and shapelessness, gambles on Washington holding the whole thing together with his usually bankable presence. For once, that’s a sucker bet.

Note: This is a review of the version of Roman J. Israel, Esq. that screened at the Toronto International Film Festival. The version opening in theaters this week is reportedly a few minutes shorter—which, honestly, can probably only help.