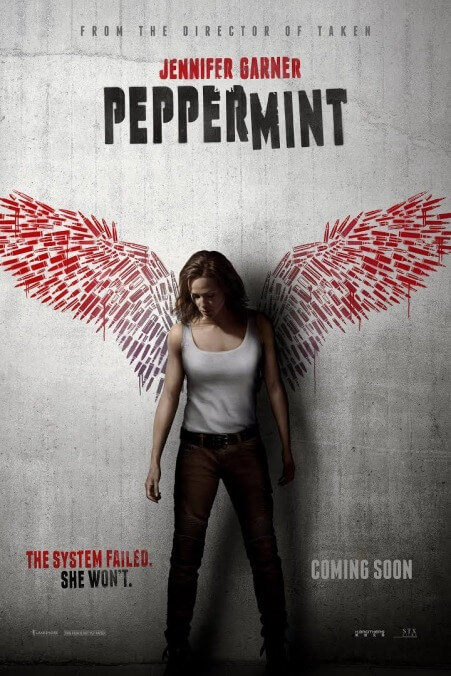

Despite Jennifer Garner’s efforts, Peppermint fails on nearly every level

At some point during the development of Peppermint, somebody had a great idea. Like a flashback to the candy-colored past, it’s easy to imagine that meeting. A golden moment. An uncut gem of an idea waiting to be shaped into something splendid: “What if we put Jennifer Garner in a John Wick movie?” Conjuring that meeting does not make the experience of Peppermint more enjoyable. What if this grotesquerie of wasted potential is the closest we ever get to a Jennifer Garner John Wick? Can this really be all there is?

It’s easy to see both John Wick and Taken, the best-known title in director Pierre Morel’s filmography, in the list of ingredients that were tossed together to make Peppermint—a list that also includes the comic book character The Punisher and his subsequent screen adaptations, one of which is credited to this film’s screenwriter, Chad St. John. There’s bloodlust and brutality, grim humor and efficient violence, workmanlike treatment of injuries, and amorality as a given circumstance. But while the influences vary in quality, each outpaces its descendant in nearly every way. Action, cinematography, scoring, thematic resonance, editing, production design—all lackluster, at best. Yet what makes Peppermint such a frustrating experience is the one way in which Morel’s film matches up to its predecessors: It centers on a performance by an actor made for this sort of work, a visceral, vulnerable, sometimes darkly funny performance of great vitality. In this case, it’s a performance that succeeds in spite of, not because of, the film, and its pleasures don’t make up for the landscape in which it lives. On the one hand, Jennifer Garner deserves far better. On the other, she cashed the check.

Garner plays Riley North, a wife, mother, and narratively convenient bank employee whose life disintegrates when a drug lord (Juan Pablo Raba) gets wind of a crime her husband (Jeff Hephner) definitely did not commit. His innocence is significant, because Peppermint’s bloodlust leaves no room for any sort of nuance when it comes to morality. In an early scene, Riley’s daughter, Carly (Cailey Fleming), tells her mother she should have punched a mean mom’s lights out; Riley responds that punching people who are jerks “makes you just as bad as they are,” and that’s about all St. John has to say on the subject. Despite the husband’s innocence, both he and Carly are gunned down, ice cream cones in hand. Justice is not served. Fast-forward five years, and Riley has completed her transformation into a gun-stealing, cage-fighting, explosives-wiring, wound-stapling vigilante with a cool haircut. There’s no hint of how she developed this very particular set of skills, or why she chose this path and not another—the film just skips ahead to the blood, guns, muscles, and murdering of bad guys.

It’s easy to identify the bad guys, because nearly all of them are Latinx. St. John’s apathy toward anything resembling complexity of thought makes this particular choice especially unnecessary and off-putting; the film doesn’t even feint at developing these characters, exploring the drug trade, or asking why they became the murderous, soulless, bad men the movie makes them out to be. They’re just here to be bad and die violently, with vague references to “the cartel” peppered in to make it clear that, yes, they are extremely bad. Morel infuses Riley’s recollections with desaturated, choppy footage that evokes Saw by way of Sicario, showing us the people on her to-kill list as masks of remorselessness with face tattoos. She stalks them through drug labs and piñata warehouses. The film cares about the stalking and the killing, not the people being killed; their arbitrary brownness makes the film’s giddy brutality disturbing in a way that’s (hopefully) unintentional.

It’s a shame, because Garner’s herculean efforts throw the film’s sloppiness into even sharper relief. Like Keanu Reeves, Garner has a gift for making every kick, punch, bullet, and desk dropped on someone’s head feel like a spontaneous decision. In the film’s best—and often funniest—moments, she gives that violence emotional substance as well, whether she’s terrifying an alcoholic father into getting his shit together or allowing herself the pleasure of clocking someone who really has it coming. Elsewhere, Morel is as disinterested in her character as he is in her targets, her trauma, or the film’s themes. For most of the film, she’s a wife and mother, but nothing resembling a fully drawn woman. But in those rare moments, Riley North becomes a person: a violent person, a broken person, but a person who might be enjoying herself a little all the same. It’s nice to see her having a good time. At least someone is.