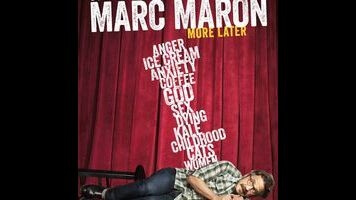

Despite what his “inner blogger” thinks, Marc Maron is winning in More Later

The definition of stand-up comedy has broadened in recent years, and it will only continue to do so. When so-called alternative comedy expanded the boundaries of the form, it unshackled many comics from the confines of setups and punchlines and finely tuned, five-minute bits. As a result, it’s difficult to look at the comedy of (just one example) Bill Burr and call it the same thing as the comedy of (another example) Kyle Kinane. In a very real sense, they’re different things.

Which brings us to the comedy of Marc Maron, which is on sound display in his newest hour, More Later. Maron is and always has been far from the conventional comic: The building blocks of his sets aren’t “bits,” per se, and Maron himself even seems shocked when he pulls out a wrench from the classic comic’s tool belt. Extremely and painfully self-aware, Maron’s comedy is ambling and discursive; if he were to perform the same set twice in one night, it’s a good bet that entire segments would be dropped, truncated, or expanded upon. He’s an artist who’s at his best when he’s able to tap into and harness the energy of the moment, sitting in whatever it is he creates and trusting in the process. Little feels planned.

Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. The title of the comedian’s first premium-cable special in two decades comes from the sign-off of the “inner blogger” Maron summons to criticize More Later as the set unfolds. Funny at first, and less so as the hour proceeds, the aside is reminiscent of the high-pitched, secondary voice Jim Gaffigan adopts to punctuate many of his expertly prepared bits—a device that only serves to detract from the comedy. The inner blogger overstays its welcome in More Later, but because Maron’s comedy exists to such a large extent in the moment, in never feels contrived.

By his own admission, Maron’s not as angry as he used to be, but this is still a man who is capable of stringing the words “Shut the fuck up” and “I am sorry” together in one extended breath. He knows he can still fly off the handle, and while he can’t completely prevent himself from yelling at you, he does promise to tighten up the space between outburst and apology. Maybe it’d be better to call Maron a “confessionalist,” a guy who’s most comfortable detailing his drug-inspired ice cream fetish as well as his penchant for conversing with his cats. But whereas the Maron of a few years ago was, despite his aggression, an endearing, anxious curmudgeon, the current Maron seems, by contrast, a bit sunnier—albeit with a “river of rage” running through him.

Saying at the outset of More Later that he’s a twice-divorced 51-year-old with no children and a couple cats, he uses the words “fucking amazing” and “I’m winning” to describe his present state. And that’s because he is indeed winning. Maron’s the comic whom all the others respected but the audience never showed up for. Now he’s so hot that a big-five publisher wants his book, a television network wants his show, and the leader of the free world wants to spend an hour with him in a garage. At times it seems like his awareness of these victories has spawned a germ of gratitude, which occasionally colors the canvas Maron casts his comedy on. While there was often an air of underlying dread and misery at the root of Maron’s work, now it feels as if there’s a bit more relief—a paean to making it through to the other side. Yes, there are anxieties and neuroses running rampant throughout More Later, but rarely do they come close to consuming the message. Instead of acting as the basis of the perspective, now they’ve nestled on the side as one (admittedly integral) part of it.

Near the top of the special, Maron says bluntly, “I don’t know what to do sometimes,” which is pretty much the hook for his comedic essence—a genuine yearning to understand himself that is constantly in conflict with the unyielding desire to escape from it. All the while, through his relentless and earth-shaking need to (over)confess, the audience gets pulled along for the ride, seeing pieces of their own fucked-up selves in the fucked-up guy sitting on the stool. And for a comic who does five minutes about the perplexity of Jesus, the self-sacrifice shouldn’t be lost on anyone.