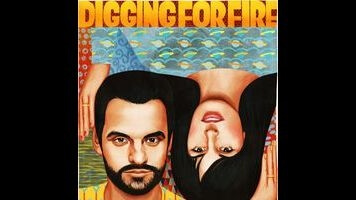

Digging For Fire makes a clunky metaphor for marriage

Early in Digging For Fire, Tim (Jake Johnson) excitedly informs his wife, Lee (Rosemarie DeWitt), that he’s just found a pistol and what appears to be a human bone buried in the hillside near their house. Well, it’s actually not their house—Lee is a yoga instructor, and one of her celebrity clients has asked the couple to housesit for a few weeks while she’s away on location shooting a movie. That only heightens the mystery, though, and Tim is gung-ho to keep digging, see what else he can find. Will he find… fire? Obviously not, and it’s disappointing to realize that director Joe Swanberg (Drinking Buddies), who co-wrote the screenplay with Johnson, intends the objects found in the hillside to function as a big, clunky metaphor. This is a movie about marriage, and its lesson is decidedly cautionary: Some things are better left buried.

To illustrate this, Digging For Fire quickly splits Tim and Lee apart, following them for the duration on separate but parallel tracks. Lee takes their young son (played by Swanberg’s son, Jude, who previously appeared in the director’s Happy Christmas) to stay with her parents (Sam Elliott and Judith Light) while she visits a friend (Melanie Lynskey). The friend bails on her, however, and Lee winds up getting a bit too intimate with a random guy (Orlando Bloom) who suffers a deep cut on his head while gallantly trying to get rid of a drunk dude who’d been hitting on Lee. Meanwhile, back at the celebrity’s house, Tim holds a pool party with some bros (Mike Birbiglia, Chris Messina, Sam Rockwell), then gets chummy with a young woman (Brie Larson) who’d tagged along. Some heavy flirting and kissing ensues, and both Tim and Lee are clearly tempted to cheat. But then there’s that hole in the hillside, and what looks like it might be an actual body.

Not to put too fine a point on it, this metaphor is stupid—partly because it’s a cliché, but mostly because Swanberg and Johnson make its meaning so obvious that even little Jude couldn’t possibly miss it. Nor does the movie have anything especially incisive to say about the difficulties of marriage. It separates its main couple right off the bat, provides each of them with an opportunity to stray, and concludes that they shouldn’t. (“Marriage counselors hate this movie! Click here to discover its one weird trick.”) Mostly, the film seems like an excuse for Swanberg to provide every actor he knows with a meaningless bit part: In addition to all the folks named already, there’s Ron Livingston as Lynskey’s husband, Jenny Slate as one of Lee’s yoga clients, and Anna Kendrick as another woman at the pool party, who coincidentally turns out to be a med-student friend of Orlando Bloom’s character and stitches up his head wound.

With so much talent involved, there are inevitably some amusing moments, which keep tedium at least partly at bay. Birbiglia has fun as the group’s Jiminy Cricket, forever urging his buddies not to transgress, and Larson is pure playfulness. What’s more, Johnson and DeWitt have great, spiky chemistry together during the movie’s opening scenes, which only makes it all the more frustrating when they spend the next hour and change apart in the service of a hoary moral about leaving well enough alone. We see too little of their relationship to be invested in its survival, which means that the slew of familiar faces primarily serves as a distraction from the empty hole at the movie’s center. Those shovels are useless.