Airborne automobiles zig and zag around spiral chrome towers. Hover rails, the latest in speedy mass transit, offer another route across this shiny cityscape, passing through looped, gravity-defying parks. Jetpacks are an everyday convenience. So too are rockets, sending the casual skygazer careening towards the cosmos. Tomorrowland, the utopian metropolis of Disney’s new tentpole fantasy, is less a vision of the future than a peek into the past—the space age that only a mid-century society, drunk on wonder and new advances in transportation, could have envisioned. The anachronism is very much by design: Positing that the only way to move forward may be to go back, Tomorrowland aches for an era when people were still hopeful about where the world might be headed. It’s nostalgic for a future that never happened.

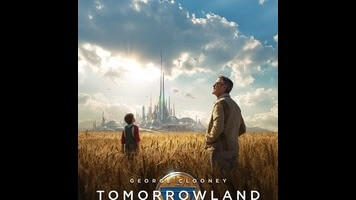

This is one strange contraption of a movie, a $200 million exercise in corporate synergy that’s also an earnest passion project for nearly everyone involved. The inspiration, if that’s the right word for talking about an amusement-park adaptation, is one of several themed areas featured at various Mouse House entertainment destinations. (Disneyland makes an early cameo, if only to remind kids in attendance that the real Tomorrowland is just a summer vacation away.) But the film feels equally animated by the fixations of its star, George Clooney, who seems to genuinely believe in the ability of Hollywood cinema to change the world, and the obsessions of director Brad Bird, offering another vaguely Randian ode to “special people.” For a family film, it’s both appropriately zippy and—here and there—oddly violent, with robot faces mashed out of shape by baseball bats and hapless police officers reduced to piles of ash.

Less a city of the future than a kind of alternate-dimension incubator—think Silicon Valley by way of the World’s Fair—Tomorrowland is off limits to all but the biggest dreamers and most intrepid innovators, who earn their invitations by thinking outside of the box. Who built this fantastical planned community, and how long has it been yanking the world’s brightest minds from their humdrum existences? With Damon Lindelof (Lost, Prometheus) sharing screenwriting duties with Bird, it’s no huge shock that the details are either sketchy or convoluted. The place itself, though, is a sight to be seen. Our first sustained look occurs when conspicuously named teenage dissident Casey Newton (Britt Robertson, possibly a hologram of pure optimism) comes into possession of a mysterious pin. Each touch replaces her surroundings (NASA’s backyard, Cape Canaveral) with images of the eponymous city. Appropriately, this experience—conveyed in a single, winding, awestruck take—is not unlike a 3-D, hyper-advanced version of one of those Universal Studios rides where a huge screen creates the sensation of moving through a fictional world.

Investigating the origins of her magic device, Casey gains a couple of uneasy companions: Frank Walker, a former boy genius and Tomorrowland recruit who’s grown into a bitter middle-aged man (Clooney); and Athena (Raffey Cassidy), the precocious, ageless robot girl who ushered him into the brain trust and then broke his heart. Overlong flashbacks, featuring a lot of corny jet-pack humor, set up this central relationship. It’s somehow both oddly touching and a little creepy to see Clooney play jilted, betrayed romantic against a little girl, even if the character she’s portraying is technically older (and much less human) than Frank.

Building off of the retro futurism of The Iron Giant and The Incredibles—not to mention the tech wizardry of his fantastic Mission: Impossible sequel—Bird keeps throwing new kinds of gee-whiz spectacles at the audience. One set piece involves a stealth function for the Eiffel Tower; another introduces a godlike answer to Google Earth, allowing our heroes to scroll through both space and time with the roll of an oversized trackball. The best of these gimcrack effects sequences finds Casey and Frank fleeing a squadron of mechanical G-men in a booby-trapped house, the enemies felled by various high-tech weapons and tools. Bird stages the PG mayhem with his usual grasp of dimension and space, his gift for action that’s timed like physical comedy. He keeps the whole thing moving, even when it begins to feel bogged down by preachiness and sci-fi exposition.

“I get things are bad,” someone says early into the movie. “But what are we doing to fix it?” Tomorrowland, at its core, is about the self-fulfilling prophecy of defeatism—the way that gloom and doom predictions about the future have relieved people of the responsibility of caring. (The villain, who students of Ebert’s Law should have no trouble identifying, delivers a pretty pointed monologue about apocalypse apathy.) That’s a nice message for a hyper-visible studio event movie to impart; sending viewers, especially young ones, out on a hopeful note is a noble goal, even within the context of a cross-promotional blockbuster. But who, exactly, will be making these seismic societal changes? As in The Incredibles and Ratatouille, Bird flirts heavily with exceptionalism, again suggesting a hard line between superior citizens and mediocre masses. That makes Tomorrowland’s call to action feel weirdly exclusionary, as though saving the world were a job fit only for the chosen few—the renaissance men and women, the brilliant elite, the George Clooneys of all walks. The fight for the future, like Tomorrowland, is apparently by invitation only.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.