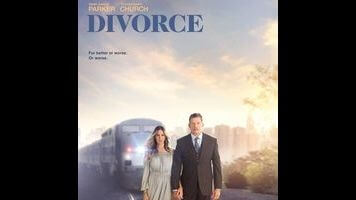

Divorce doesn’t get as nasty as it should

HBO’s Divorce begins with a 50th birthday party gone bad. The fete is being thrown for Diane, a wine-guzzling Westchester resident played by Molly Shannon. That Shannon was once known for proudly declaring “I’m 50” as Sally O’Malley on Saturday Night Live adds a little bit of meta-textual humor to the scenario. But, unlike Sally, Diane is not proud of her age. This is a gathering filled with middle-age ennui that turns volatile, and the raucous events inspire the protagonist, Diane’s friend Frances (Sarah Jessica Parker), to tell her husband, Robert (Thomas Haden Church), that she wants a divorce, setting the plot in motion. The laugh-out-loud viciousness of the opening, which involves both a gun and vomit, is clearly the work of series’ creator Sharon Horgan, who also co-writes and stars in Amazon’s brilliant Catastrophe. But Divorce isn’t always as biting as it is in those moments, leading to a solidly acted but somewhat mundane exploration of a breakup.

That’s somewhat to the point. There’s no real hook here: These two are a run-of-the-mill couple living in the upper-middle-class New York suburbs. She works as an executive recruiter, while he remodels and resells houses. Their distaste for one another has been festering for a while, but their animosity is manifested in passive-aggressive gestures rather than drag-out fights. Although they’ve both made transgressions—some arguably worse than others—neither is a villainous party: Both sides are justifiable and unreasonable in equal measure. Horgan and her team are mostly interested in how small infractions can shift the path of the divorce proceedings. It seems strange that any plot point from this show could count as a spoiler, but almost every episode has a mini shocker that alters the power dynamic between Frances and Robert. Just when you think their situation is going to be handled one way, it goes another. It’s a small feat.