Doctor Who: "Boom Town"/"Bad Wolf"/"The Parting Of The Ways"

“Boom Town” (season

1, episode 11; originally aired 6/4/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix,

and Amazon Instant Video.)

“Just go in there and

tell her the Doctor would like to see her.” “Doctor who?” “Just the Doctor.

Tell her exactly that. The Doctor.” “Hang on a tick… The Lord Mayor says

thank you for popping by. She’d love to have a chat, but, she’s up to her eyes

in paperwork. Perhaps if you could make an appointment for next week?” “She’s

climbing out of the window, isn’t she?” “Yes, she is.”

When Russell T. Davies delivered his Doctor Who pitch document to the BBC in the fall of 2003, he

already had clear plans in mind for almost all of the stories that would

ultimately comprise the revival’s first season. The lone exception, as Shannon Patrick

Sullivan’s indispensable “A Brief History of Time (Travel)” explains, is “Boom

Town.” In his original vision for the season, Davies knew he wanted an episode

spotlighting the new, three-person TARDIS team in action—indeed, the episode

was simply referred to as “The New Team”—between its formation at the end of

the preceding story and its dissolution in the concluding two-parter. Beyond

that, Davies’ only longstanding goal with the episode that became “Boom Town”

was to save money, as a smaller-scale episode 11 would help ensure that the two-part

season finale could be as epic and ambitious in scope as possible. While every

story evolved significantly from its description in the 2003 document to its

ultimate televised form, “Boom Town” is unique in that it didn’t actually snap

into place until another story had actually been filmed.

“Boom Town” exists in its present form because, more than

anything else, Russell T. Davies was impressed enough with Annette Badland’s

performance in “The Aliens Of London”/“World War Three” that he decided to

bring Blon Fel Fotch Pasameer-Day Slitheen—alias Margaret Blaine—back for a

return engagement. So many of the logical problems with this episode fall away

if one keeps in mind that Badland’s return was an overriding goal of this

episode, rather than a natural byproduct of the storytelling process. It doesn’t

really make a lick of sense that Margaret Blaine could, in the space of six

months, become Lord Mayor of Cardiff and ram through a major proposal to build

a nuclear power station in the very heart of the city, all without so much as

having her photograph taken or attracting any attention from London.

Admittedly, Davies does win points for audacity with his attempt to paper over that

last logical gap, as Margaret takes on the local neuroses when she says London

couldn’t care less about what happens to Wales. It’s also an open question why

Blon doesn’t just leave behind the Margaret skin suit—as one of her Slitheen

brothers swapped bodies in “Aliens Of London”—and hide inside someone who isn’t

potentially a prime suspect in the recent alien invasion (although at least

Margaret never actually appeared in any of the newscasts in her debut

appearances). But then, that all ignores the essential point: If Blon had

changed bodies, Annette Badland couldn’t have returned.

These issues can all be rationalized away, and pretty much

every Doctor Who story requires some amount

of rationalization, but “Boom Town” asks for significantly more suspension of

disbelief than the typical episode, and we haven’t even reached the ending yet.

This story’s closest equivalent is “Father’s Day,” which similarly

deprioritizes the strict logic of its narrative in order to focus on the

personal story between Rose and her father. The precise mechanics of the

Reapers and the paradox are underexplained at best, but that’s because they are

beside the real point of the story. The handling of the Doctor in both stories

is a good clue; much as the Doctor matter-of-factly told Rose in the earlier

episode that he could do anything, here he and his growing team of companions

make short work of Margaret. The chase sequence is played strictly for laughs—the

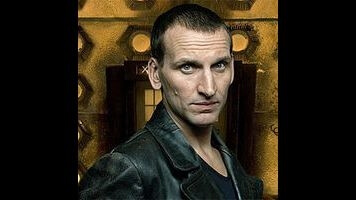

exchange up above is one of my favorite gags of the Eccleston era—and there’s

never any question that the Doctor can outwit Margaret and anticipate her every

escape attempt, at least until the moment that her real trap is sprung. Davies’

script purposefully treats the plot as an afterthought, all the better to focus

our attention on the real crux of the episode: the Doctor and Margaret’s dinner

date.

Their discussion of the morality of the Doctor’s actions

could quite happily have gone on for much longer than it actually does. The

first of the two major exchanges at the restaurant addresses the Doctor’s

uncomfortable place as enforcer of the law. There are alternatives here that

aren’t considered—even if Raxacoricofallapatorius is unacceptably barbaric in

its punishment, there are surely other, more civilized worlds that would gladly

incarcerate a Slitheen, possibly even including Earth—but what really matters

here is that the Doctor lowers his defenses enough to actually ask Margaret

what else he can do. As Jack warns him back in the TARDIS, Margaret is just

trying to get into his head, and it’s actually when the Doctor thinks he has

Margaret properly sized up as a killer with an occasional, arbitrary capacity

for mercy that his dining partner manages the most piercing blow. The viewer

doesn’t need to accept Margaret’s argument that compares her own killer’s mercy with

that of the Doctor, because the really significant action of the scene is happening

in Christopher Eccleston’s eyes. Badland’s own performance makes it clear that

Margaret is just trying every line of attack she can find to weaken the Doctor’s

resolve. It doesn’t work, necessarily, but the Doctor realizes he cannot entirely

rebut the notion that he is, for all his good intentions, a destructive, even

capricious force in so many lives.

Unfortunately, “Boom Town” couldn’t realistically have

stayed in that restaurant for the remainder of its running time, because something

resembling a plot has to kick back in eventually. “Something resembling a plot”

is about right, since the climax is pretty much gibberish. The fact that

Margaret had a nefarious backup plan all along doesn’t entirely undermine her

earlier attempts at contrition, but it does muddy waters that already weren’t

terribly clear. The actual resolution, in which Margaret stares into the heart

of the TARDIS and is regressed into an egg, is one of the strangest, most

random endings in the show’s history. Again, going back to “Father’s Day,” not every

plot element in that episode makes as much sense as perhaps it absolutely

should, but the core story—Rose’s rash decision to save her father, and then

her father’s decision to sacrifice himself to save everything—makes emotional

sense. It’s a story whose resolution “feels right” because it’s a natural

outgrowth of the relationship built up between Rose and Pete over the course of

the story.

Margaret’s fate is far less clearly motivated; the best

suggestion I can offer is that the power of the time vortex is the tangible

manifestation of the Doctor’s godly side, and so this represents his ability to

find alternative solutions that would be impossible for mere mortals. For that

to really work, though, the episode would need to engage more directly with the

show’s more mystical elements; as it is, the ending comes out of nowhere, so it’s

hard to treat it as anything other than a convenient way for the Doctor to duck

an insoluble dilemma. In its way, “Boom Town” feels less like an episode of Doctor Who than it does a foray into The Twilight Zone, as the show’s more

familiar narrative beats are downplayed in order to focus on a particular

what-if scenario. The dreamlike logic of this story’s resolution does feel like

the sort of thing Rod Serling might have come up with (although perhaps not in

one of his better efforts), as the most important thing about Margaret’s fate

is not that it makes strict narrative sense or even that it lets the Doctor off

the hook. No, the real key is that in some bizarre, cosmic sense, justice has

been served, and Blon Fel Fotch Pasameer-Day Slitheen got what she deserved. “Boom

Town” is an oddity, and not a particularly successful one, but it’s the sort of

failed experiment that demonstrates Doctor

Who’s renewed vitality. And now for an episode that pushes that idea even

further.

Stray observations:

- Since there’s so much ground to cover today, I’ll be keeping these to a minimum, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Rose and Mickey’s reunion, which might actually be the most effectively handled plotline in the entire episode. Russell T. Davies, Billie Piper, and Noel Clarke manage to hit just the right balance, as Rose and Mickey discuss their rather unique relationship problems in ways that transcend petty issues of who is “right” and who is “wrong.” The resolution, in which Mickey leaves before Rose can find him again, is a difficult one to take, but it does suggest that both parties are moving on a little wiser about just who they are. That said, I’m glad they end on rather better terms in “Parting Of The Ways.”

“Bad Wolf” (season 1,

episode 12; originally aired 6/11/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix,

and Amazon Instant Video.)

“No! Because this is

what I’m going to do. I’m going to rescue her. I’m going to save Rose Tyler from

the middle of the Dalek fleet. And then I’m going to save the Earth, and then,

just to finish off, I’m going to wipe every last stinking Dalek out of the sky!”

“But you have no weapons, no defenses, no plan.” “Yeah. And doesn’t that scare

you to death. Rose?” “Yes, Doctor?” “I’m coming to get you.”

Since we’re talking about the non-narrative motivations

behind these scripts, it’s also worth pointing out that “Bad Wolf” exists in

its present form because Russell T. Davies—or, more precisely, the Russell T.

Davies of 2003 to 2005—loves reality shows. The use of Big Brother, The Weakest Link,

and What Not To Wear is an

illustration of the author’s fascination, if not outright affection, for this

particular genre. As a reviewer, that places me in a tricky position, because,

at the risk of being blunt, I hate reality television; worse, I find these

sorts of shows deathly tedious. That antipathy is doubtless at the heart of my

logical objections to this premise, namely that any of these shows would endure

in the human (or, for that matter, Dalek) consciousness for almost 200,000

years. On a really basic level, I find that silly, even though a considerably

more extreme version of this joke was already made with the “Toxic” gag in “The

End Of The World.” Still, that was only a throwaway gag, while here the reality

shows form the central mystery of the first half of the 9th Doctor’s final

adventure. Nine years on, that still feels wrong,

somehow, although I’m willing to accept that “Bad Wolf” may simply be

irreconcilable with my preferred vision of what Doctor Who should be. That can happen with a premise as infinitely

expansive as Doctor Who; any good

showrunner has to narrow it down to a vision he or she finds most compelling,

and that process is always going to leave some portion of fans behind.

Right, that’s enough bloviating self-indulgence. (I’m sorry

it dragged on that long, honestly.) The fairest way I can see to approach “Bad

Wolf” is to ignore the specifics of the reality shows, at least temporarily,

and consider instead their function in the story. All of these, essentially,

are gladiatorial games, a hybridized form of randomized punishment and sick

entertainment that keeps the human population equal parts terrified and

pacified. They are designed to turn a once mighty species, the would-be

architects of the Fourth Great and Bountiful Human Empire, into livestock, and

even that might be giving humanity too much credit. This isn’t a million miles

away from the ideas explored in the 6th Doctor story “Vengeance On Varos,”

which is one of Colin Baker’s best outings (and yes, I do think that’s saying

something), so it’s possibly just the presence of specific copyrighted logos that I

object to, which does seem a bit silly on my part. Indeed, even if Davies’ fondness for reality TV led “Bad Wolf” to

incorporate actual shows and cast their real-life hosts in voiceover cameos,

the episode still stands as something of a rebuke to the genre and television in

general. Reality television has helped enslave and stupefy the human race. That’s hardly a ringing endorsement.

There’s also an element here of writing toward the biggest episode-opening shock. The Doctor can travel anywhere in space and time,

which means there are vanishingly few places where even he would be surprised to

find himself. Throwing the Doctor—particularly one as serious and haunted as

Christopher Eccleston’s incarnation—into the middle of the Big Brother house is a willfully insane scenario, and Eccleston

himself almost makes the whole gag work with his dumbfounded, “You have got to be kidding me.” The trouble is

that “Bad Wolf” then has to explain that joke, and a scenario so purposefully

ludicrous that it would work best as a throwaway gag has to be the foundation of the entire rest of the episode.

The Doctor finding himself on a deadly reality show could

serve as the setup for some incisive, witty social commentary—a 21st century

“Vengeance On Varos,” basically—but it’s a less obvious lead-in to this

Doctor’s ultimate showdown with the Daleks. In fairness, the reality show setup does offer an apparently harmless starting point from which the situation can spin hopelessly out of control,

as the Doctor begins “Bad Wolf” a mix of puzzled and annoyed before everything

goes to hell about ten times over. The Doctor has let his guard down, and he

pays dearly for his inability to recognize the seriousness of what’s going on

around him. That point is most obviously made when he realizes that his refusal

to stick around after “The Long Game” is what helped create this current mess,

but the Doctor spends the entire story being maneuvered and manipulated by those who know more than

he does: first the Game Controller, then the Daleks, and always, always the Bad

Wolf.

One of the more curious aspects of this story is the

introduction of Lynda with a “y.” The character herself isn’t particularly

interesting; she’s basically what one would build out of a companion-by-numbers

kit. But that’s exactly the point: In the absence of Rose, the Doctor strikes

up a new friendship with another human, going so far as to invite her along on his

travels in the TARDIS. After an entire season built around Rose and her

importance to the Doctor—a theme that reaches its absolute crescendo in the

next installment—it’s strange, though hardly objectionable, to see the Doctor so readily recruit a new

companion. His interaction with Lynda is an intriguing counterpoint to his

conduct in “Rose,” as he is ready and willing to befriend whichever stupid ape shows a little compassion and intelligence. More than that, he

now believes that standing next to him is the safest place a person can be; the

time he has spent with Rose has restored his belief in the essential rightness

of his actions. In his own mind, he is once more the heroic savior instead of the grim

avenger, and he’s now ready to bring a nice person like Lynda into his world.

Part of the tragedy of the next episode is just how wrong that belief turns out to be.

But before that, the Doctor and Jack must deal with Rose’s

apparent disintegration. Director Joe Ahearne—who also helmed “Dalek,”

“Father’s Day,” “Boom Town,” and “The Parting Of The Ways”—is in the conversation

for the title of Doctor Who’s best ever director, and “Bad Wolf” is at its most striking when the Doctor and Jack

briefly appear defeated. It may be a coincidence—or just a byproduct of Billie

Piper’s distinctive gait—but Rose’s dash from the Weakest Link set to the Doctor seems to recall Rose’s run towards

the TARDIS at the end of the premiere, which neatly emphasizes just how deadly

this once magical adventure has suddenly become. Crushed by the death of Rose,

the Doctor simply ignores his latest incarceration. Doctor Who has a long tradition of

locking the Doctor in a jail cell as a way to pad out a story’s running length,

but the Doctor has never seemed so uninterested in the whole affair. In

particular, the quick shots in which a broken Doctor has his mug shot taken

don’t feel like elements that quite belong in Doctor Who, and I mean that as a positive. Usually, the acting, the dialogue, or even the music would somehow indicate that the Doctor is above the piffling affairs of mortals, but here he is allowed no such detachment. For those fleeting moments, the situation feels

hopeless in a way so few Doctor Who threats

ever do.

It’s hard to imagine that little sequence playing out in

quite the same way in the David Tennant or Matt Smith eras, let alone in the

classic series, because those are the kinds of scenes that are made when those

making the show don’t quite know what the hell they are doing. Indeed, that’s

the more positive manifestation of the same anarchic, irreverent impulse that

birthed the deadly reality shows. For better and worse, “Bad Wolf”—one half of the final collaboration between

Russell T. Davies, Christopher Eccleston, and Joe Ahearne—represents Doctor Who at its most unpredictable, at

its most dangerous. In its way, that might honestly be the most impressive

achievement of the show’s revival, even if I don’t always like the results.

Stray observations:

- The Weakest Link sequence does actually manage some legitimate suspense, with much of the credit for that going to Anne Robinson and Paterson Joseph. The latter has often been rumored as a leading candidate to play the Doctor, and I honestly hope the window hasn’t yet closed for that happen. Joseph isn’t very Doctor-ish here, admittedly, but he absolute commits to what could otherwise be a ridiculous sequence. If he doesn’t give the quiz show sequences his all, it’s likely I’d take a far dimmer view of “Bad Wolf” than I do already.

“The Parting Of The Ways”

(season 1, episode 13; originally aired 6/18/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix,

and Amazon

Instant Video.)

“Do you know what they

call me in the ancient legends of the Dalek home world? The Oncoming Storm. You

might’ve removed all your emotions but I reckon right down deep in your DNA,

there’s one little spark left, and that’s fear. Doesn’t it just burn when you

face me?”

The Doctor closes out “Bad Wolf” with the rousing speech that

I quoted at the top of that episode’s review, and one of his first speeches

here is the business about the Oncoming Storm quoted above. Both are brash,

bold moments, expressions of angry defiance that stand in stark opposition to

the abject terror that the Daleks clearly provoke in him elsewhere. This story isn’t

the first time that the Doctor has spoken so fiercely to his archenemies—the

7th Doctor had a particularly awe-inspiring monologue in the fantastic “Remembrance Of The Daleks”—but the Doctor usually waits until he has the upper

hand before unloading on the Daleks like he does here. In these speeches, the

Doctor unleashes the man he became during the Time War, an identity he has

gradually abandoned over the course of this season. He is enraged, he is proud,

and he is merciless. He makes a threat, but more than that he makes a promise.

He promises death to the Daleks and salvation to Rose and all humanity. So what

do we make of an episode—the last stand of the 9th Doctor, no less—in which he

completely and utterly fails to keep that promise?

I’ve probably come further in my opinion of “The Parting Of

The Ways” than I have any other Doctor Who episode. When I first watched this

episode nearly nine years ago, I didn’t care for it at all, and now I’m dangerously

close to declaring it one of the very best regeneration episodes, assuming I’m

allowed to split off this individual installment from the inferior “Bad Wolf.”

I’ve been writing about this story for years—in the interest of full, somewhat embarrassing disclosure, here’s one effort to articulate my

thoughts from back in 2010, one more from 2009, and there’s another, even older screed buried

somewhere in the archives of the Gallifrey Base fan forum—and, after all this time, my opinion of this episode has improved so drastically that I’m down

to my two last salient criticisms. The first has to do with how the episode

uses Christopher Eccleston in his valedictory performance as the Doctor, which

goes back to the question I asked above.

What I never quite appreciated until rewatching the episode for this review is that the entire point of the story is to depict what happens on the worst possible day of the Doctor’s life. After the relative frivolity of “Bad Wolf,” this episode starts with the Doctor facing the worst threat imaginable, and so much of this story consists of simply witness the Daleks mow down all opposition. As Russell T. Davies would later prove with “Midnight,” “The Waters Of Mars,” and Torchwood: Children Of Earth, his writing is at its sharpest when his worldview is at its grimmest. This is a harsh, hopeless story, one in which a companion knowingly prepares to meet almost certain death in order to buy the Doctor some time. As regeneration stories go, “The Parting Of The Ways” rivals the granddaddy of them all, “The Caves Of Androzani,” in its uncompromising bleakness. Peter Davison’s swansong at least allows his Doctor to focus all his remaining energy on saving the life of his companion amid the unspeakable carnage; in a sense, that’s also what “The Parting Of The Ways” is all about, but this episode takes a more circuitous path to this Doctor’s ultimate sacrifice.

Honestly, I’d be willing to accord “Parting Of The Ways”

classic status right here and now if not for one brief scene. It’s the one

where the Doctor asks Lynda about the rest of the Dalek fleet, and she reports

the invasion force has launched a devastating attack on Earth, one in which

entire continents appear to melt and reshape themselves. The carnage that comes

with such an attack must be incalculable, to the point that it’s hard to know

how much of humanity is even still around to be wiped out by the Doctor’s delta

wave. Just like the reality shows’ millennia-long survival, this is an instance

where Davies seems to lose all sense of narrative scale, as the

instant death of what could well be several billion people seems to render moot

the battle on Satellite Five or the Doctor’s moral dilemma. The situation would

be just as hopeless and the Daleks just as fearsome if their actions were

restricted to the satellite. Without that scene, “Parting Of The Ways” would

still be a brutal, propulsive episode in which the Doctor and his friends find

themselves completely outmatched. The Doctor could still fail, and the

vortex-infused Rose could still redeem him, without Earth being obliterated.

That’s been my read of the scene for the better part of nine

years, at any rate. What I never quite considered is the possibility that

Davies never intends the Doctor’s dilemma to be whether he should wipe out humanity

in order to stop the Daleks—the point articulated there would basically boil

down to “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” with the “few”

in this case referring to humanity and the “many” being the rest of the

universe. It’s certainly possible to agree with that viewpoint and still be

heroic, but that’s never really been a principle the Doctor has been

comfortable with; he was unwilling to sacrifice Rose to save the planet back in

“World War Three,” after all. The devastation of Earth restricts the Doctor’s

dilemma still further, so that the moral question is less about whether he is

willing to wipe out the remnants of humanity and more about whether he is

willing to wipe out the Daleks themselves. If that reading is accurate,

it wouldn’t be the first time that the Doctor has wondered whether he has the

right to commit genocide against the Daleks; famously, that very question forms

the climax of the Tom Baker classic “Genesis Of The Daleks.”

Admittedly, I’m not entirely convinced by this argument,

especially since Bad Wolf Rose’s actions are plenty genocidal. The moral

argument of “Parting Of The Ways” is muddled, but perhaps the mistake is to think that

Davies’ intention is to make a universally applicable point. Really, whatever

this episode has to say about right and wrong is all to do with the Doctor. After

all, as he boasted in “Dalek,” he wiped out the entire stinking species at the

end of the Time War, and that action was the most primal violation of all he

stands for; in that earlier episode, he only had to point a gun at one Dalek for Rose to consider him

unrecognizable. The Time War cost him a part of his identity, and his refusal

to repeat that genocidal action in “The Parting Of The Ways” is what reaffirms that

the Doctor is truly the Doctor once more. He fails to save just about anybody,

but he refuses to be the killer, the destroyer of worlds. If it is time for him

to die, at least he can die as the Doctor. As I’m sure I once heard somewhere,

it’s better to fail doing the right thing than succeed in doing the wrong.

And if all that doesn’t entirely work, well… the Doctor has spent his day

being ranted at by a Dalek with delusions of godhood. That would be enough to

put anyone in a bit of a weird headspace.

Still, the resolution is the ultimate manifestation of one

of the most persistent criticisms of the 9th Doctor, namely that he is

sidelined when it comes time to resolve the central threat. After all, he

needed Rose to save him from the Nestene Consciousness, Gwyneth to repel the

Gelth, Mickey to launch the missiles at 10 Downing Street on Harriet Jones’

order, Cathica to overheat the Jagrafess, and Pete Tyler to make the ultimate

sacrifice twice over; even in “The Empty Child”/“The Doctor Dances,” the

story in which the Doctor takes by far his most active role and is directly

responsible for ensuring that everybody lives, he still needs Nancy to accept

her responsibilities as a mother and Jack to intercept the German bomb. This

Doctor is not defined by his own deeds but rather the heroism that he inspires

in others. He is an aspirational figure, someone whose absolute idealism and

willingness to fight the toughest foes inspires others to be their best selves.

And anyway, the Doctor is, by his nature, an interloper; as he points out in

“The Parting Of The Ways,” he and Rose are free to leave at any time, even if

neither he nor the people he chooses to travel with would ever choose that

option. On some level, it’s only right that people like Gwyneth or Cathica or

Nancy are the ones who vanquish the monsters, because they are the ones whose

ordinary, humdrum lives have been reshaped by that threat. The Doctor is always

on hand to save the day, but it’s rarely his day to save.

That isn’t the case in “The Parting Of The Ways,” in which the

invading Dalek horde is something out of his worst nightmares. Indeed, the most

haunting moment in the story—hell, perhaps the entire run of Doctor Who—is the shot of a traumatized,

nearly broken Doctor pressing his head against the TARDIS door, trying to shut

out the screams of the Daleks outside. This is a cosmic, all-encompassing

threat, precisely what the Doctor faced during the Time War. The Doctor knows this is his battle to win or to lose, but he now lacks the outsider’s perspective that makes him so good at finding the solutions that others cannot. He is too consumed with his own grief and guilt and rage; he makes an honest effort to defeat the Daleks at beyond impossible odds, but he ultimately realizes that the only choice he can make is whether he wants to die as the Doctor or as a killer. Just this once, he needs other people to solve his own problem, and there’s no better way to take the measure of a Doctor than to look at his companions.

I realize I haven’t written much at all about Captain Jack Harkness in these last two reviews, which is more of a reflection of just how ridiculously much there is to say about these five final episodes than anything else. Jack’s transformation from self-interested rogue to noble, self-sacrificing hero is slightly underwritten, if only because the stories themselves have so much other ground to cover; in an ideal world, Jack’s arc would have benefited from one additional story between “The Doctor Dances” and “Boom Town” that helps show how he forged such bonds with the Doctor and Rose. As it is, John Barrowman is at his best in “The Parting Of The Ways,” playing Jack as the very rarest of Doctor Who characters: a companion who follows orders without question. He trusts the Doctor so implicitly that he is willing to place himself between the Daleks and the Time Lord, a decision that the Captain knows will cost him his life. His farewell scene, in which he kisses both the Doctor and Rose, is a lovely moment, as Jack is finally, absolutely redeemed for whatever crimes he may have committed in his past. Strictly speaking, Jack might have been better off as a coward who never met the Doctor, but the Doctor would never have survived as long as he did without everything Jack does for him here, which makes the Doctor’s apparent decision to leave him behind all the more heartbreaking.

And then there’s Rose. Her big speech to her mother and Mickey about what the Doctor represents—not giving up, making a stand, and having the guts to do what’s right when others run away—is an apt summation, and it’s fitting that Rose is only able to become the Bad Wolf with the help of Mickey, Jackie, and, indirectly, Pete. “The Parting Of The Ways” is at its most poignant in its 21st century story, as Davies, Ahearne, and the team of Billie Piper, Noel Clarke, and Camille Coduri wring all possible emotion from the situation. After all, Rose can only meet her cosmic destiny at the Doctor’s die when those who love her most agree to effectively sever ties with her, a point that Mickey in particularly understands all too well. Rose is absolutely right: The Doctor makes people better, and it’s frankly astonishing just how much better Mickey and Jackie have become since their borderline embarrassing debuts.

Look, the Bad Wolf is a deus ex machina, and in a fairly literal sense, too. There really isn’t much new to say on this point, but it’s worth pointing out that a deus ex machina is merely a potential indicator of bad writing; it isn’t proof of bad writing in and of itself. No, scattering the words “Bad Wolf” throughout the season and what happens to Margaret in “Boom Town” do not represent adequate setup for Rose’s transformation into a godlike being, but this is another instance where I would argue emotion and character really should trump plot. The Bad Wolf destroys the Dalek threat in an instant, setting right what the Doctor cannot, but that’s only because the Doctor’s refusal to commit genocide has earned him that salvation. The ending is also an expression of all that the Doctor and Rose mean to each other, which is something I promise we’ll discuss in more detail down the road—though, for the record, I wouldn’t personally consider this Doctor’s kiss to be romantic in the way we humans would typically understand the term. In that moment, the Doctor and Rose achieve a level of mutual understanding that the Time Lord almost never experiences. When Rose says she can feel the universe itself, the Doctor is no longer alone, yet he must take that all away just to save her life.

It’s a small sacrifice, really, even if it does cost the Doctor this particular daft old face. This was a Doctor never entirely comfortable in this particular skin, and so it’s sadly appropriate that he only seems properly at peace with himself when he’s on the brink of regeneration. The 9th Doctor’s entire existence can be thought of as one extended regeneration; the Time War was so devastating to the Doctor that he needed an entire incarnation just to heal himself. When discussing Christopher Eccleston’s decision not to return for the 50th anniversary special, Steven Moffat observed that “The 9th Doctor turns up for the battle but not the party.” Admittedly, he was as much talking about Eccleston as he was the 9th Doctor, but the description fits them both. This first season was a battle for Doctor Who’s survival, and the fact that the show won over the public almost immediately doesn’t take anything away from the magnitude of that struggle. Christopher Eccleston played a Doctor unlike any other, and it’s doubtful we will see his like again for some considerable time, at least not until the show needs saving and reviving once more. Eccleston and the 9th Doctor both brought the show back and, more importantly, paved the way for it to become something altogether different, something even bigger and wilder and madder than what the show could achieve in its first year back. That’s a damn fine legacy to leave behind, even if I do wish it had taken Eccleston more than just 13 short episodes to create it.

Stray observations:

- I think we’re all just about ready to wrap this up, but I really should acknowledge the new man who makes his debut in the story’s closing seconds. Admittedly, my main thought here is, “Wow, David Tennant looks so young here.” 2005 really was such a long time ago…

- At the risk of getting into spoilers, you may have noticed from a line or two in this review that I’m comparing “Parting Of The Ways” with “The Day Of The Doctor.” On balance, I’d say the fundamental points that both stories make line up well, with the 9th Doctor’s arc in this story recalling both that of the War Doctor and the 11th Doctor. The major differences between the two can be explained by the differences between 9 and 11 and between Russell T. Davies and Steven Moffat, but the ideas and themes in both strike me as highly compatible. If the 9th Doctor doesn’t make the decision to be “a coward” here, it’s fair to say the 11th Doctor would never have the chance to grow into the kind of man who can find an even more audacious solution. But yes, I know not everyone is going to agree on this point.

- This Week In Mythos: Yes, this section still exists, in case anyone was wondering. There are two major, if oblique, references in tonight’s episode. First, the Doctor mentions the Dalek home world, although he doesn’t actually name it specifically. Regeneration is obviously the major concept reintroduced here, although that exact term is never used, as the Doctor simply refers to it as a way of cheating death. Once again, this show is meticulous in how it parcels out information.

Next week: A new

era begins with the 10th Doctor’s debut, “The Christmas Invasion.” I’ll also be

taking a look at the mini-episode that David Tennant and Billie Piper filmed

for Children In Need. Hopefully, that review will be considerably shorter than

these last two epics. I mean, my goodness…

“Rose, before I go, I

just want to tell you, you were fantastic. Absolutely fantastic. And do you

know what? So was I.”