Doctor Who: “Kill The Moon”

For its first 20 or so minutes, “Kill The Moon” is fine. There’s plenty of tension and suspense as the Doctor, Clara, Courtney, and their newfound astronaut allies explore the impossibly heavy Moon, discover the disquieting remains of the Mexican survey team, and survive attacks from bacteria the size of badgers. The episode only struggles slightly because that central mystery—seriously, how did the Moon suddenly add the ridiculous amount of extra mass needed to make its gravity equivalent to that of Earth?—is so huge, so goofy, so beyond our pitiful human comprehension that the episode can’t really snap into focus until it’s resolved. And, 20 minutes in, we get our answer, as the Doctor, joyous and awestruck in a way that we’ve so rarely seen in this incarnation, explains that what we think of as the Moon is really just the shell for the biggest egg in the universe, and that egg is hatching. This is Doctor Who at its most lovably preposterous, showing its willingness to tackle literally any concept. It’s taken a little while, but “Kill The Moon” now has its premise. The only question now is what happens next. And what happens next represents 25 of the best, most important, and most heartbreaking minutes in Doctor Who’s long history.

As soon as the Doctor finishes his monologue about the lunar egg, the audience knows a twist is coming. The first such narrative pivot is so familiar that I’ll call it the “Midnight” turn. Just as the passengers on that besieged bus responded to the 10th Doctor’s appeal to the best of the humanity with a moment’s pause and then a cold consensus that all were willing to kill the monster, so too does Hermione Norris’ astronaut break the silence by asking the Doctor how they can kill the Moon. It’s not an unexpected development, really, but it’s a necessary signal that the episode is about to get serious. The show has found a terrific moral dilemma for itself, one with plenty to say about the Doctor; after all, he’s a unique creature about to witness the birth of another unique creature, the very existence of which has clouded his knowledge of the cosmic timeline. Defending the lunar creature is just the kind of opportunity we’ve been waiting for, a real chance for this Doctor to show his idealistic bona fides and help show the astronaut a better way. It definitely wouldn’t be the first time we’ve seen that on new Doctor Who. Nah. This episode has something far darker, far more controversial in mind.

“Kill The Moon” is the second time this season that Doctor Who has genuinely surprised me. That fact, above all else, is why tonight’s episode and “Listen” rate as instant classics. Neither episode is flawless, and neither represents the show heading into bold new territory on a plot level. Just as “Listen” could not exist without every previous Steven Moffat-penned exploration of childhood fear, “Kill The Moon” can feel almost derivative of earlier moral dilemmas in space, most notably “Midnight” and “The Waters Of Mars.” But what both “Listen” and “Kill The Moon” do is take all that familiar material and use it to play with our most basic assumptions about what Doctor Who is. Somewhere around the halfway mark of both episodes, they take sharp turns away from what eight seasons of new Doctor Who has taught us to expect. After nearly a decade back on the air, there are only so many ways for the revived series to genuinely shock its audience. These two episodes accomplish that feat by weaponizing our own narrative expectations and turning them against us.

That’s a neat storytelling trick, but then Steven Moffat’s tenure as showrunner has never been short on such cleverness. Don’t read that as too much of a backhanded swipe—I dearly love episodes like “The Wedding Of River Song,” which is pretty much exclusively narrative pyrotechnics—but what has made these two episodes so powerful and the season in general such a return to form is the renewed emphasis on character. The Doctor’s pursuit of a non-existent monster and his decision to leave the humans to solve their own crisis exist not simply to deconstruct the tropes of past Doctor Who stories, but more importantly to help us better understand who the Doctor is. And what’s really remarkable is that these two episodes, so similar in their broad approach, end up taking us in diametrically opposed directions. Both stories present the Doctor at his most alien and remote; after seven seasons spent getting to know this Time Lord, he has never felt quite so much like a stranger, nor quite so dangerous. “Listen” ultimately circled back, using the Doctor’s manic episode to reveal his all too human fears and frailties. That episode ended in a place of love and understanding. But “Kill The Moon” makes him, if not precisely the villain, then at least something as far away from a hero as he’s been in a long, long time.

We need to ease into this one, because “Kill The Moon” takes the hardest narrative left turn in Doctor Who’s 51-year history. This episode, this season, maybe the whole damn Moffat era is going to be defined by that final scene in the TARDIS, in which Clara delivers the most blistering rebuke we have ever seen any companion give the Doctor. It’s a brutal but absolutely necessary scene, one that finally articulates in uncompromising fashion what is so fundamentally troubling about the Doctor’s relationship with humanity, his favorite pet species. Again, you can see how crucial “Midnight”—before this season, easily Doctor Who’s fiercest deconstruction of itself—to this episode’s creative DNA; if “Listen” took that episode’s unseen, unknowable monster to its logical conclusion, then “Kill The Moon” takes the examination of the Doctor’s flawed, imperious relationship with humans to its breaking point. But who could have ever predicted that result at the outset of this episode? (Excluding those who read the behind-the-scenes previews and stay up to date on spoilers, that is.) Theoretically, the original point of the entire lunar exercise was to prove that young Courtney Woods was special. Or, more accurately, for the Doctor to avoid addressing whether he actually thinks Courtney is special.

But then, that scene in the hallways of Coal Hill School between the Doctor and Clara is only the first scene chronologically. The actual first scene of “Kill The Moon” comes before the credits, as we see part of Clara’s desperate message to Earth. So much time elapses between the credits and the rest of the message that it’s easy to forget that the episode even begins in media res, but in retrospect that scene plays like the cruelest joke on the audience, and perhaps a bit of devious reverse psychology. After all, that pre-credits sequence tells us that Clara and Courtney must make an impossible decision, weighing the life of an innocent against the fate of all humanity, but it also tells us that the Doctor isn’t there to help. And, honestly, if you had given me a hundred guesses as to where the Doctor is during that scene, I’m not sure it would have occurred to me that the Doctor would have just left. He could have been captured, or he could have headed off on some equally important side mission to buy them some time, or he could have seemingly died, no doubt in some heroic sacrifice. But for the Doctor—even this Doctor, a far more difficult and unpredictable incarnation than most—to just abandon his friend and all humanity in their darkest hour? I never would have guessed that without seeing it happen.

That’s not to say that the Doctor’s decision here has no prior precedent. The Doctor has always been maddeningly inconsistent about what he can and can’t do, and how much he is and isn’t bound by the laws of time. He repeatedly tried to leave the crewmembers of Bowie Base One to their terrible fate in “The Waters Of Mars,” and his ultimate interference remains the 10th Doctor’s gravest error. That same incarnation was all too prepared to leave the people of Pompeii to their deaths, and it was only at Donna’s insistence that he saved even four people. (Well, perhaps he just liked Caecilius’ face.) Some instances where the Doctor refused to get involved were relatively benign: Consider the 9th Doctor’s insistence that humans should be left to handle first contact by themselves in “Aliens Of London,” or the 11th Doctor’s decree that only humans and Silurians could be involved in the peace negotiations in “The Hungry Earth”/“Cold Blood.” On some level, what we’re dealing with here is the writers’ own imperfect attempts to explain why the Doctor gets involved sometimes and why he doesn’t in other instances. “Kill The Moon” has the Doctor make all the standard arguments about how his temporal vision is imperfect and how he can’t change the course of truly momentous events, though it’s hard not to think the show is purposefully undermining his point by having him repeatedly mention not killing Hitler, when that’s totally a thing he almost did. (Not that he ever meant to, but still.)

But again, “Kill The Moon” isn’t primarily interested in wrestling with abstract matters of metanarrative or whatever the hell else. The Doctor abandons Clara for reasons so obscure that even he doesn’t appear to understand them. His is not a logical decision, but it damn sure is the decision of an officer, and an aristocratic one at that. There are so many ways to analyze that final scene between Clara and the Doctor, and I’ll get to some more when in a little bit, but consider the one line that the Doctor says without a trace of confidence or certainty, as though it’s the one moment in which even he doubts his own bullshit. He tries to argue that he left because that was his way of respecting Clara. Again, we’ll come back to Clara’s response, but consider the implication of that line: If abandoning Clara was a sign of respect, what does that mean for every instance in which he stays to help? Does he ever respect Clara, let alone any human who doesn’t travel with him in the TARDIS? If he sees his default role as a kind of cosmic chaperone, then that leaves precious little room for friendship. After all, friendship implies equality.

According to Doctor Who Magazine, episode writer Peter Harness—who makes one hell of a debut here—originally penned “Kill The Moon” as a story for Matt Smith’s 11th Doctor. Frankly, I find that impossible to believe. I mean, I can just about see how you could make this story work for the 11th Doctor, as he absolutely had his own dark and manipulative streak, but that was so often tempered by what Madame Vastra identified in “Deep Breath” as his desire to fit in; he might have talked a big game about just leaving, but some combination of curiosity and loneliness—and, sure, maybe compassion—would have forced him to stick with the humans. “Kill The Moon” derives so much of its power from the presence of the 12th Doctor, because this is another episode that makes good on Vastra’s promise that this is a Doctor without disguise or affectation. Every Doctor would have been tempted to do his Time Lord duty and leave the human race to its pivotal decision, but this is the first Doctor in a long time who feels him Time Lord side so keenly as to actually follow through on it, and his disinterest in human niceties means he’s particularly cruel in his goodbye to Clara. But then, a good general doesn’t motivate his troops by being nice to them. The Doctor probably does have absolute faith in Clara’s ability to make the right decision, but that’s because he has trained her well, not because he trusts his friends.

As for Clara, I’ve got to admit I didn’t expect the show to pay off so immediately Danny’s concerns from “The Caretaker.” There really isn’t enough praise to be given both to Harness’ script and to Jenna Coleman’s performance in that final scene. Going back to my Clara discussion in “The Caretaker,” this is where Clara’s status as a less well-defined companion actually serves the show. From the beginning, Clara has always been defined in terms of the Doctor; this season has been far smarter about delineating why the Doctor needs her, positioning her as something between carer and psychiatrist, but she is still a character whose primary trait is her absolute belief in the Doctor. And yeah, that’s true of every companion, at least in new Doctor Who, but that defines her so much more than anything else, so it’s all the more heartbreaking when it’s she, the companion defined again and again by her absolute belief in the Doctor, whatever form he takes, whom the Doctor betrays. When Clara banishes the Doctor and calls him out for every last detail of his hypocrisy, she speaks for every companion, every insignificant human the Doctor has ever used, manipulated, or otherwise relied upon to make a difficult decision that he could not stomach doing himself.

And yet, Clara does so in a way that is uniquely her. It’s not a coincidence that Clara’s three best moments on the show—her interrogation of Skaldak in “Cold War,” her confrontation with the Half-Face Man in “Deep Breath,” and now this scene—all find her on the verge of the tears, and Doctor Who has never once suggested this is a sign of weakness or vulnerability. (Well, “Cold War” considered the possibility, but then David Warner dismissed the idea, and I’m not going to disagree with David Warner.) Clara has been hurt by the Doctor on the most fundamental level, and the fact that she never hides the depth of that hurt during the confrontation is a sign of incredible strength. What’s more, it’s a kind of strength that feels a million miles away from the “strong female character” archetype we’ve seen so often in the Moffat era; hell, it’s hard not to see some real world-parallels when Clara furiously calls out a middle-aged Scotsman for all the ways his treatment of her is thoughtless and patronizing. Whoever wrote that scene—it’s hard not to think Steven Moffat didn’t have a hand in it, at least in the rewriting phase—it plays like a much larger acknowledgment of the show’s past shortcomings, and the fact that the Doctor ultimately just has to shut up and take it is what makes it feel so revolutionary. In the meantime, I might well have been wrong in my review of “The Caretaker,” as the show just gave Clara one hell of a vital character arc to play out over the next five episodes.

As I said a couple thousand words ago, “Kill The Moon” isn’t perfect. As I say, the episode is fuzzier than it strictly needs to be in the early going, and the supporting characters are underwritten, to put it mildly; Hermione Norris’ main astronaut is named Lundvik, but I’m pretty sure there’s only a single, contextually unclear mention of that before the closing credits. Lundvik is basically just Adelaide Brooke from “The Waters Of Mars” with the serial number filed off; the episode basically relies on our familiarity with this particularly Doctor Who character archetype to lend Lundvik a specificity that isn’t really present in the script. Still, writing is only half of what makes up a character, and “Kill The Moon” benefits tremendously from Norris’ performance. She hits just the right balance between steely determination, broken idealism, and occasional flashes of warmth, and it’s a clever touch to have her so immediately accept that the Doctor and Clara are time travelers; once again, this is an episode that does not engage in unnecessary obfuscation, all the better to focus on what’s really going on between the characters.

Besides, just as last week’s “The Caretaker” actually worked better because Clara is less sharply drawn than previous companions, so too does “Kill The Moon” rely on archetypes. The back half of this episode is very much a morality play, and we don’t really need the characters to fulfill anything more than a trio of symbolic roles. Lundvik is the scared person willing to make the hard choice, Courtney is the innocent who cannot countenance such a transgression, and Clara is the good person trying to find the right decision. The Doctor’s own assessment of his three chosen humans fits with this reading. Compare this episode to the last time the Doctor donned that spacesuit, last year’s “Hide.” That’s an episode where the 11th Doctor repeatedly exhorts his newfound allies to action with individualized pleas; he talks of how the characters will do what they do because they are Emma Grayling and Alec Palmer and Hila Tukurian. But here, the new Doctor won’t go into more detail than saying a schoolteacher, an astronaut, and a teenager should be sufficient to find the right answer. In a particularly detached early moment, he even asks what Courtney Woods is. The Doctor has to make an effort to connect with people as individuals, and his downfall in this episode is a complete lack of effort.

Perhaps that’s too close a reading; overanalysis is often an issue with Doctor Who. But the thing about this show is that it’s almost impossible to get everything from watching an episode only once. As I discussed last year in my review of the deeply flawed but fascinating “Nightmare In Silver,” a lot of that is down to the wild variance in what a Doctor Who episode looks like week to week; almost nothing about “The Caretaker” can prepare audiences for the genre conventions and storytelling choices found in “Kill The Moon.” Sometimes, as with “Nightmare In Silver,” it takes a couple watches just to get what kind of story an episode is trying to tell. “Kill The Moon” isn’t in that territory, even if the first half of the episode is decidedly richer once you can watch again with the knowledge of what’s to come. But this is an episode that absolutely nails its plot beats, its moral dilemma, its exploration of the Doctor’s failure, and Clara’s rejection of him.

Whatever minor flaws this episode has, it gets all the big-picture stuff absolutely right on the first watch, and that opens the door for thematic deep dives on subsequent viewings. I already mentioned how the pre-credits sequence becomes a bit of particularly brutal foreshadowing, but it’s also possible to fit in little, seemingly disconnected moments—like, say, Clara lecturing the Doctor on her duty of care to Courtney—to the Doctor’s own failures to humans, Clara above all. This is an episode that we’re going to be talking about for a long, long time. Even after 3,000 words, I can’t help but feel I’m only scratching the surface of all this has to say about the show and its main character. This season is already a return to form, but “Kill The Moon” could help turn it into something truly special.

Stray observations:

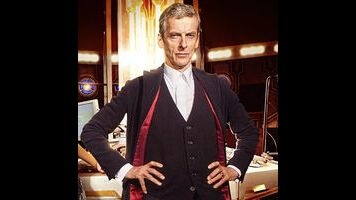

- I took a break from praising Peter Capaldi this week, but yeah, he remains absolutely fantastic in the role. He’s absolutely terrifying when he tells Clara it’s time to take the stabilizers off her bike, but he’s also crucial to the success of the final scene with Clara, as he masterfully allows the Doctor’s confidence and bluster to ebb away. Oh, and his sudden onrush of knowledge about the future of humanity is really nicely done as well, as though a wave of time is washing over him. Pretty sure my three-way tie for favorite Doctor is now a four-way tie.

- Ellis George is also excellent as Courtney Woods. It’s so easy to misfire on these teenage brat characters, but a big point of this episode is she isn’t really a brat; yeah, she hasn’t found a place to fit in yet, and she can’t resist giving Clara some guff about wanting to have kids with Mr. Pink, but overall she shows considerable resolve in asking to come back and fight for the Moon’s right to live, even after she was understandably traumatized by her encounter with the bacteria.

- Speaking of Danny Pink, Samuel Anderson makes the most of his short appearance here. After being the undeniable focus of “The Caretaker,” it’s nice to see Danny shift into a supporting role here, offering some good insight about why Clara isn’t done with the Doctor, at least not yet. Also, his line about wisdom coming from a really bad day has plenty of echoes with the Doctor’s own experience. Perhaps turning his worst ever day into his best one in “The Day Of The Doctor” has actually robbed him of some hard-won wisdom.

- The Tumblr discussion is a really nice touch, particularly as Lundvik talks about it as something practically prehistoric. Plus, like “Russian,” “Tumblr” is a word that sounds really adorable in Jenna Coleman’s Blackpool accent, so that’s a plus.

- “Prat.” Truer words have never been spoken, Lundvik. Well, word. But yeah, it’s the right thing to say right there.