I might run out of superlatives for this one. I’m prepared to take that risk…

“Listen” is the best Doctor Who episode in years. More than that, it’s the best story Steven Moffat has written for the show since “The Eleventh Hour,” and I might be willing to go still further back than that in search of an episode of his that outdoes tonight’s entry. (Honestly, I’m considering a fairly pitched battle for supremacy between this and “The Empty Child”/“The Doctor Dances.”) Like so many of Moffat’s best efforts, this episode is simultaneously concerned with exploring childhood fears and deconstructing the Doctor Who mythos; indeed, this story brilliantly combines these two overriding obsessions, as we are asked to wonder whether we should really take seriously the Doctor’s latest mad theory of impossible monsters hiding in plain sight. This episode is clever in the way that so many of Moffat’s scripts are, but the difference here is that that cleverness is not the core of the episode. Instead, “Listen” is defined by its compassion: for Clara, for Danny and Orson Pink, and ultimately for the Doctor himself. Deconstructions can be great fun—once again, I’m a complete sucker for them—but for once Moffat also aims to build new understanding. The result is an episode that features all the thematic density and twisty storytelling that defines Moffat’s era, placed in service to the kind of warmth and humanity that more defined the work of his predecessor.

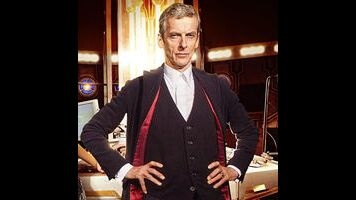

It’s also the perfect showcase for Peter Capaldi and his Doctor. There’s this notion—a valid one, I think—that we shouldn’t think of “Doctors” but instead of just one singular “Doctor,” with the differences in appearance and personality merely obscuring the universal traits shared by every incarnation. Indeed, the emotional climax of this story depends on that notion, as Clara talks to the little boy who will grow up to look like William Hartnell about his final adventure as John Hurt, all while Peter Capaldi recovers in the TARDIS; it probably helps that we’re only dealing with the three oldest incarnations, but this only works if we remain focused on the Doctor as a single individual. All that said, each Doctor will have adventures that so completely rely on that actor’s particular interpretation of the Time Lord, to the point that it would be impossible to tell the story with any other incarnation. There are relatively few of these. “Into The Dalek,” for instance, could still work with any of the other new series Doctors; the points of emphasis would change a bit for the 9th Doctor and a hell of a lot for the 10th and 11th Doctors, but the story would still essentially work. Not so for “Listen.”

That’s because this episode reveals just what Capaldi brings to the Doctor that distinguishes him from his all his predecessors: He is utterly insane. We’re not talking about madness here, because a madman in a box—the 11th Doctor’s favored self-description—suggests a kind of charming eccentricity that’s oh so very English. Well, this Doctor isn’t English. (For those who don’t mind a mortar shell blast of profanity, Capaldi would be happy to elucidate his feelings on the subject.) This season has suggested a minimalist Doctor, with the assumption being that beneath his predecessors’ affectations lie ruthlessness and rage—the darkness that the Doctor flashed in “Deep Breath” and alluded to in “Into The Dalek.” But “Listen” suggests something even scarier: Lurking underneath that daffy curiosity and sense of adventure that so animated his immediate predecessors is an obsessive need to know everything, to take the unknown and the unknowable and bring it all to heel. As Clara suggests toward the end of this episode, it’s okay for the Doctor to be scared. What’s not okay—and what’s absolutely, captivatingly terrifying in the hands of Capaldi—is that he won’t admit that he’s just afraid for no good reason.

“Listen” could only ever be a 12th Doctor story, for no other Doctor would be honest enough with himself to allow his obsessions to consume him, even if he still can’t bring himself to admit why. All the previous Doctors allowed themselves to be distracted from that insane curiosity at the core of their being; some by the bonds they forged with their companions, some by an idealistic belief in some grander mission, and, in the case of the other barking mad Doctor, by the desire to have fun. Capaldi turns in a suitably fearless performance, reaching his obsessive crescendo as he prepares to meet whatever is waiting for him at the end of the universe. But he layers in more subtle manifestations of his compulsion, playing the Doctor that much more distracted and bored by humanity than he is usually. Even in his most accessible moment, when he tries to comfort Rupert, he’s colder and more calculating in his advice than we’ve come to expect from the Doctor. He’s not telling Rupert that fear is a superpower because he wants the frightened child to feel better, but rather because he genuinely believes that’s what the boy needs to know. As “Listen” ultimately reveals, that’s the Doctor’s great ongoing mistake, all because he can’t bring himself to admit that he too was once scared for no good reason.

Let’s step back for a moment, because “Listen” accomplished something that’s damn rare for Doctor Who these days: It showed me something I hadn’t seen before. Never mind that Doctor Who has been running for 51 years (or 34 seasons and a TV movie, if we want to get technical). The new series alone is now in its eighth season, and it’s only the constant turnover in casts and creative teams that distracts us from the fact that eight years is a long, long time for any show to run. We’re comfortably past the hundred-episode mark, so it shouldn’t really be surprising that it’s harder for Doctor Who to feel fresh, to surprise its audience. I really liked both “Into The Dalek” and “Robot Of Sherwood,” but those both felt of a kind with previous episodes; the former made no secret of its “Dalek” influences, while the latter was a particularly swashbuckling take on the pseudohistorical adventure. And yes, “Listen” counts several past episodes as influences, a point I’ll get to in a moment, but its tone is what sets it apart, what makes it feel unlike any other Doctor Who story I’ve seen. This is a meditative, reflective episode, one unafraid of exploring the negative space and wondering whether monsters are only really there because we so desperately need them to be. This is the kind of story that requires a Doctor capable of sitting still, and that, eight years into the new series, is a definite novelty.

But it’s the little moments that tend to stay with you, and the one random yet indelible image I can’t shake from “Listen” is of a dazed Clara walking away from her second failed attempt at a date with Danny Pink and back into the TARDIS. As Clara herself says, this is a surreal sequence, the absurdity of it all brought out both by Douglas Mackinnon’s subtly off-kilter direction and by the shell-shocked expression on Jenna Coleman’s face. It’s a powerful moment because it cuts right to the essence of an idea that Steven Moffat has explored throughout his era, and arguably as far back as “The Girl In The Fireplace”: the clash between real life and Doctor life. This is where the decision to make Clara a companion who does not travel permanently with the Doctor really pays off. The new series has explored the private lives of its companions before, in some cases in far greater detail than we’ve seen with Clara, but the show has never before been able to just have a companion go on a date. When previous episodes have explored such contrasts—think “The Power Of Three,” another Mackinnon-directed episode—ordinary life could only really be viewed in big-picture terms, as that giant amorphous clump of existence that took shape only when the Doctor wasn’t looking.

Clara and Danny’s date, on the other hand, is a discrete slice of normality, and that again allows “Listen” to focus in a way that the show wasn’t really built to do during the 11th Doctor’s tenure. Employing the same non-linear storytelling we saw in “Into The Dalek,” the episode basks in every element of exquisite awkwardness. For those few minutes after the opening credits, “Listen” is pure relationship drama, exploring how the pair’s obvious attraction to one another is not yet enough to bridge the vast divide in their experiences and perspectives. Danny’s first appearance only had time to establish his soldier past in the broadest of brushstrokes, and “Listen” brings specificity and sensitivity to that backstory. Samuel Anderson nails Danny’s angry, flustered monologue about digging all those wells, as he conveys the sense that Danny has recited that speech countless times, even if just in his head. What Steven Moffat’s script and Coleman’s and Anderson’s performances bring out is the all too relatable experience of a fight that happens for no discernible reason, as these are two people—romantically inclined or otherwise—who are desperate to make peace with each other but who keep making it worse with every renewed effort. There’s some pitch-perfect cringe comedy to be found here, particularly when Clara tries to remember just who at the school told her Danny’s real name, but there’s also such a recognizable humanity to these scenes that isn’t always present in Moffat’s scripts.

I mention Danny’s real name, which is something Clara only knows about because the Doctor takes her on an inadvertent tour of Pink—and maybe Oswald—family history. This is the other side of that juxtaposition between real life and Doctor life, as Clara is left to wonder just how much of her own destiny she is being given casual glimpses of, and just how much of said destiny is of her inadvertent creation. “Listen” doesn’t even vaguely hide the fact that young Rupert is going to change his name to Danny, but the episode finds a clever, heartbreaking twist when it reveals that Clara—with quite a bit of help from the Doctor’s psychic “dad skills”—is the person who implanted “Dan the soldier man” in the boy’s subconscious. As has so frequently been the case this season, “Listen” draws heavily on Clara’s experience caring for children, as she quickly bonds with Rupert and attempts to make him feel better about his fears. It also sets up a crucial parallel with her subsequent scene in the barn, making it clear that she comforts the crying Gallifreyan not because Clara exists only to comfort the Doctor—a sense one could occasionally get last season—but because she can’t resist getting involved and helping whenever there’s a crying child. She’s like the Doctor that way.

Returning to the scene at the children’s home, it’s another example of how this season has benefitted from slowing down the pace of storytelling. In previous seasons, Doctor Who moved at such a breakneck pace that those kinds of character moments became mechanistic, just another item on the narrative checklist. Here, Clara and Rupert are given time to talk, not as characters en route to the next plot beat in a horror story, but as two people trying to forge a connection. That focus on emotion instead of suspense makes it all the more terrifying when that mattress suddenly sinks. The old tricks feel new again, if only because “Listen” isn’t primarily concerned with the coolness of those tricks.

In examining this episode’s creative DNA, it’s not hard to see its thematic forerunners. Creatures that have evolved perfect hiding are just the latest Steven Moffat monsters that represent primal childhood fears; at first glance, they sit right next to the clockwork droids, the Weeping Angels, the Vashta Nerada, and the Silence. There are times in “Listen” where the echoes of past stories become particularly strong: The outpost at the end of the universe recalls “Utopia,” the unseen monsters owe a debt to “Midnight,” the children’s home in Gloucester is like the Silence-infested orphanage in “Day Of The Moon,” and the stranded time-traveler (and the episode’s general spookiness” is borrowed from last year’s “Hide.” The reason “Listen” still feels fresh, despite all those influences, is that it is a progression of the ideas raised in those earlier stories, not a remix. For instance, if “Midnight” gave us a story where the nature of the monster was beside the point, then “Listen” gives us one where the existence of the monster is essentially irrelevant. That the entire threat exists only in the Doctor’s head isn’t just a possible explanation, but the most plausible one. On that level, the narrative parallels have their uses; the Doctor’s conversation with the night watchman about disappearing coffee mugs might recall Canton’s interrogation of the addled Dr. Renfrew, but the episode expertly—and hilariously—deflates the tension when it’s revealed the Doctor just stole the coffee.

This goes back to a point I originally made in my review of the Farscape episode “They’ve Got A Secret,” a story that turns on how the characters lie to themselves and to each other: “Characters in science fiction don’t lie, they create continuity errors.” For a science fiction show like Farscape or Doctor Who to hang together, the audience needs to be able to trust what it is told, particularly when the limited production budgets mean it’s not always possible to show everything one might want to see. We’re so conditioned to take characters’ pronouncements as gospel truth, because to doubt them would risk the entire damn story imploding. Go back to the scene in Rupert’s bedroom; once the initial shock of the sinking mattress wearing off, what sustains the suspense of the scene? Clara asks the obvious question about whether anyone has entered the room, and Rupert assures her that no one has. And the audience’s natural instinct is to trust implicitly the word of a terrified child who is already convinced monsters are under his bed. That’s insane, but it’s understandable. After all, Doctor Who has just spent the last decades telling us that monsters are real; the mere presence of a scared child is sufficient proof of a monster’s existence.

If this were the only point “Listen” had to make, then it would still be a fine episode. But what elevates it is the recognition that core premise of so many of Steven Moffat’s earlier scripts was incomplete. Previous scripts have told us that it’s okay to be scared because the monsters are real, and because fear can be harnessed and put to use in saving oneself from those monsters. The Doctor makes both of those arguments over the course of “Listen,” as when he comforts Rupert with the promise that fear is a superpower, then distinctly discomforts him with the harsh truth—at least from the Doctor’s perspective—that he’s never going to be safe anywhere. But “Listen” arrives at a far simpler, more mature truth: It’s okay to be afraid because there’s nothing inherently wrong with being afraid. Fear is an emotion, and the Doctor’s impulse is to respond to fear with rational arguments. But emotion and reason are not opposites; rather, each exists along its own separate spectrum. The presence of monsters cannot justify fear, because that implies their absence removes the justification.

“Listen,” at long last, recognizes the value of fear on its own terms. It’s appropriate that Clara, a companion whose best moments have been defined by her ability to overcome her own terror—think her interrogation of Skaldak in “Cold War,” her confrontation of the Half-Face Man in “Deep Breath,” or even her more mundane anxieties about her date with Danny—would be the one to offer such a tribute. It’s a gutsy move to actually go back to the Doctor’s childhood; the decision to keep the young Gallifreyan in silhouette, with only his hair and feet even briefly visible, is an acknowledgment that the episode risks compromising one of the show’s great enduring mysteries. But then, Steven Moffat has been quietly building to this scene for almost a decade; think of the 9th Doctor in “The Empty Child” saying he knows what it’s like to be left out in the cold, or of Reinette seeing the 10th Doctor’s lonely childhood in “The Girl In The Fireplace.” The Doctor didn’t run away from Gallifrey because he fitted in perfectly, after all, and this night—one of many, apparently—spent cowering in fear is just the beginning of the journey that led him to discover courage. After all, courage would be unnecessary in the absence of fear, and kindness cannot easily exist without either of them.

At its heart, “Listen” is an act of compassion toward the Doctor. Previous episodes have examined and analyzed the Doctor’s foibles, shining the spotlight on the flaws in his character that make him so much more fascinating than some boring old hero. But what far fewer stories have done is seek to understand the Doctor. It’s easy to sympathize with the Doctor when he’s being a bit of a bastard, but that’s generally a question of balancing the scales: Yes, the Doctor is in the wrong in this given situation, but he’s so often in the right that he can be cut some slack. But it’s far harder to empathize with the Doctor, because that requires us to understand the Doctor as just another person. Russell T. Davies, for all his success bringing out the emotional realities of the companions’ lives, had a tendency to keep the Doctor at arm’s length, relying on Christopher Eccleston’s and David Tennant’s acting to bring out otherwise unspoken emotions. Steven Moffat is more interested in exploring the Doctor, but generally in terms of his unique status as the universe’s greatest legend. Here, however, a particularly alien Doctor is revealed to be driven, at least in part, by the fears and dreams that haunted him eons ago. That’s not everything we need to know about the Doctor, for no one can be so easily reduced. But “Listen” is just about the most honest exploration of the Doctor we’ve seen in 51 years. That it does all this without judgment, but rather with love and understanding, is what makes it special. It’s what makes it Doctor Who.

Stray observations:

- I think I’ve probably said more than enough on this one, eh? Well, three more things, and then some quotes. Here’s the first thing: Samuel Anderson deserves all the credit in the world for making that blond afro work. Orson and Danny are obviously fairly similar characters, but Anderson finds just enough differences to make them feel distinct; notably, Orson is far less haunted than his probable ancestor, even allowing for all that time spent stuck at the end of the universe. Anderson and Coleman also remove all hints of the romantic attraction between Danny and Clara when they switch over to playing Orson and Clara, because otherwise… ew.

- I’ll admit there are a few small criticisms one could make of this episode. As with “Deep Breath,” this episode has the Doctor insult Clara for no particular reason, and I wouldn’t say any of them are really funny enough to compensate for the mean-spiritedness of the joke. The other issue one might have is that “Listen” could have foregrounded the Doctor’s obsessiveness and Clara’s own capacity for fear a bit earlier in the episode. Indeed, I tend to think that Doctor Who needs to signpost its emotional beats, because the constant shifts in time and place mean it functions a bit like an anthology show, in which we need to reset even the main characters’ main emotional beats at the start of every episode. That said, I think “Listen” is so well done that it earns the right to be a little more subtle than usual, and everything it draws upon has been previously established in the season’s first three episodes.

- For anyone unaware, Wally is better known as Waldo on this side of the Atlantic. It’s a funny gag, but also a nice way of again acknowledging the Doctor’s tendency to go searching for things that may or may not be there.

- “Isn’t it bad if I meet myself?” “It is potentially catastrophic.” “Why did you bring me out here?” “It was still talking. I needed someone to nod.”

- “Last man standing in the universe. Always thought that would be me.” “It’s not a competition.” “I know it’s not a competition. Course it isn’t. Still time though…”

- “People don’t need to be lied to.” “People don’t need to be scared by a big gray-haired stick insect, but here you are. Shut up!”

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.